![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

1

The state of the art and challenges for heterodox economics

Tae-Hee Jo, Lynne Chester, and Carlo D’Ippoliti

The objectives and unique characteristics of this publication for heterodox economics

The Routledge Handbook of Heterodox Economics is a collection of essays written by authors representing a wide range of theoretical traditions within heterodox economics. It is a project that encapsulates past and current developments in heterodox economics for the purpose of ‘analyzing, theorizing, and transforming capitalism.’

This has been an ambitious project. It is ambitious in terms of its multiple, challenging objectives that differentiate the present volume from other publications. The Handbook aims, first, to provide realistic and coherent theoretical frameworks—as an alternative to that provided by the mainstream (orthodox) perspective that dominates the teaching of economics and has informed many contemporary policies—to understand the capitalist economy in a constructive and forward-looking manner; second, to delineate the future directions, as well as the current state, of heterodox economics; third, to provide both ‘heat and light’ on persistent and controversial issues, drawing out the commonalities and differences between heterodox economic approaches; fourth, to envision transformative economic and social policies for the majority, not an elite group of the population; and, fifth, to explain why economics is, and should be treated as, a social science.

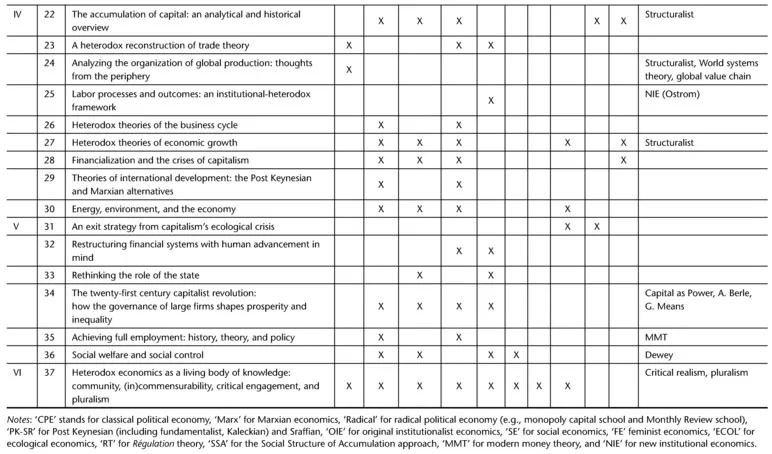

These objectives, and particularly the third, bears on the distinctive nature of this Handbook. All the chapters engage with more than one theoretical tradition in heterodox economics (see Table 1.1). This demonstrates the engagement of many heterodox economists with methodological pluralism compared to the monist methodology of mainstream economics. We, the three editors, consider that it is important to acknowledge and discuss the contributions that alternative theoretical frameworks can contribute to explaining the nature, dimensions, and dynamics of social reality. The Handbook is thus different from other handbooks and what may be considered companion volumes which explore a single heterodox school of economic thought. The Handbook’ s engagement across different heterodox theoretical perspectives does not mean the uncritical acceptance of any or all approaches. On the contrary, the contributions throughout this Handbook provide constructive critiques of heterodox approaches. This contributes, in our view, to the ongoing development of different heterodox traditions and their applications.

Table 1.1 Theoretical orientations of each chapter

It is contestable whether it is possible (or desirable) to synthesize different heterodox economic traditions. It is possible to discern similarities and compatibility between heterodox traditions; likewise, there are differences and incompatibilities. Some heterodox economists have argued that synthesis, in varying degrees, is both possible and desirable (perhaps most strongly by Lee 2009: 200–202). The activities of heterodox associations and networks—such as the International Confederation of Associations for Pluralism in Economics (ICAPE), the Association for Heterodox Economics (AHE), the Society of Heterodox Economists (SHE), and the Heterodox Economics Newsletter —tacitly, if not overtly, promote pluralism and, on occasion, have explicitly supported a synthesis of heterodox approaches.1 Others are more pessimistic about such prospects. For example, John King (2016: 10) notes that “[t]he difference within the various schools of heterodox economics—let alone between them—seem to me to be so substantial that any such intellectual Popular Front would prove to be a very unstable affair.” The difference between these two positions lies in the emphasis on the degree of similarity or difference between heterodox approaches—“a glass half-empty of coherence vs. a glass half-full of coherence” (Lee 2009: 202). We do not advocate one or the other position although we do hope that this project may contribute to the endeavors of heterodox scholars to develop more coherent and comprehensive narratives of capitalism than can be illuminated from a single perspective.

The Handbook also has the following distinctive features. First, contributions are from a mix of established and emerging heterodox economists with an emphasis on the latter. A reviewer of our Handbook proposal remarked that “the major weakness of the book is the lack of well-known authors.” We, however, think that this is a particular strength and unique feature of the Handbook. Fresh ideas and bold arguments are more often than not put forward by emerging scholars while established ones offer a somewhat more ‘predictable’ analysis given the period of time necessary to establish their careers and reputations. The evolution and development of the traditions within the heterodox economics community lie largely in, we believe, the work of emerging heterodox scholars. We hope that this Handbook provokes new directions for heterodox economics, which break from conventional understandings and practices of heterodoxy.

Another notable feature of the Handbook is that contributions are from scholars located in 16 different countries (see Table 1.2) and representing Marxian-radical political economics, Post Keynesian-Sraffian economics, institutionalist-evolutionary economics, feminist economics, social economics, Régulation theory, the Social Structure of Accumulation approach, ecological economics, and combinations of these traditions. This geographical and theoretical diversity portends well for the future of heterodoxy. Moreover, of the 44 contributors, nearly one-third are from women. This may not seem impressive and our aim was 50 percent of authors.2 This gender imbalance is very indicative of the economics discipline generally, mainstream or heterodox. It also establishes a yardstick upon which future editions of the Handbook may seek to improve.

While these are ambitious objectives and unique features, the Handbook does not strive to cover all aspects of heterodox economics. Rather than a definitive volume (we doubt that such a volume(s) is possible), the Handbook explores the theoretical and policy domains of heterodox economics. Methodology, research methods, and the philosophy of heterodox economics do not form the focus of this Handbook, although these aspects are touched upon in the following sections of this Introduction as well as in some chapters (especially Chapter 39), if relevant to the discussion of a particular issue. This is not because those areas are less important than theory and policy, but because there are already significant publications which focus almost exclusively on these areas.3 Moreover, many chapters in this volume attest explicitly or implicitly that heterodox economic theories and policies are firmly based on shared ontological foundations—for example, layered and structured reality, open systems of analysis, fundamental uncertainty, evolutionary-historical processes, and social relationships—that require multiple or mixed methods depending upon the research question at hand.

Table 1.2 The number of contributors by country

| Country | Number |

| Argentina | 2 |

| Australia | 4 |

| Austria | 1 |

| Canada | 3 |

| France | 2 |

| Germany | 4 |

| Greece | 1 |

| India | 1 |

| Italy | |

| Kenya | 1 |

| Mexico | 1 |

| Norway | |

| Portugal | 1 |

| Turkey | 1 |

| United Kingdom | 9 |

| United States | 8 |

| 16 countries | 44 contributors |

With regard to theory and policy to which the Handbook explicitly speaks, there are some omissions. For example, while there is a chapter on the banking system in the context of developing countries, there is not a chapter discussing the banking system in developed countries. The latter could have discussed the roles played by banks in the context of instability, crisis, and accumulation. A chapter on the capitalist state may have been included as well. Shedding light on the roles of the state vis-à-vis other institutions and organizations is a sine qua non of most heterodox traditions. Rather than a separate chapter on the state, this issue is discussed within multiple chapters across three parts of the Handbook— ‘Society and its institutions,’ ‘Rethinking the role of the state,’ and ‘Social welfare and social control.’ Apart from these two examples, readers might also consider there are other omissions which could form a goal for future editions.

A last distinctive feature of the Handbook is that it is not a diatribe criticizing mainstream economics. There is no doubt that criticism is an essential part of developing alternative perspectives. Past heterodox critiques of mainstream methodology, theory, and policy have led to significant progress in many traditions of heterodox economics. For this project, however, we asked contributors to focus their effort and space on discussing the capacity of more than one heterodox perspective to elucidate a topic, while limiting the critique of mainstream economics. Contributions to this volume are, therefore, not framed within mainstream logic, concepts, and frameworks—for example, the law of supply and demand or individual-rational-optimizing behavior. It is our intent to demonstrate the strengths of heterodox analysis and that the development of heterodox economic traditions can be independent of mainstream economics. Heterodox economics is not about complementing the mainstream or only standing in opposition. Moreover, while we support pluralism, theoretical eclecticism between heterodoxy and orthodoxy is not promoted in this Handbook. That is the subject of an existing discourse about the possible integration of heterodox approaches into many approaches within the monist methodology of mainstream economics— such as, experimental economics, behavioral economics, and evolutionary game theory (see, for example, Lee & Lavoie 2012).

Heterodox economics: methodology, theory, and community

What is heterodox economics? The answer to this question has been the subject of a longstanding debate by heterodox economists although no consensus has been reached. An attempt to answer this important question is necessary to the extent that this Handbook is of and for heterodox economics. In this section, we delineate a multi-layered meaning of heterodox economics, which underlies the heterodox economics community in recent decades around the world.

Heterodox economics is not a single unified school of thought. It is an umbrella term referring to various schools of economic thought distinguished from mainstream economics in terms of theory, methodology, policy prescriptions, and community. This internal diversity at multiple levels is a major reason why a definition is difficult. If heterodox economics is to be defined, therefore, a broad (or minimalist) definition encapsulating core characteristics common to multiple heterodox schools of economic thought would only be suitable. As we set out in the previous section, this is the position adopted by the Handbook and requires some elaboration in order to understand the past development and current state of heterodox economics.

First of all, the label matters since naming is a social process of identifying and, thus, positioning a particular paradigm vis-à-vis other paradigms in economics. Different labels designating a dissident paradigm in economics have been deployed—for example, heterodox, non-mainstream, non-orthodox, unconventional, post-classical, progressive, and alternative. ‘Heterodox’ economics is most widely used in academia these days, although this is not necessarily the best term for various reasons. Notably, some scholars eschew this label because of its negative connotation. In fact, the etymology of ‘heterodox’ is twofold: ‘another opinion, holding opinions other than the right’ and ‘of another or different opinion.’ In the sense of the former, heterodox economics is conventionally perceived as being in opposition to the dominant position that is orthodox (in the intellectual sense) or mainstream economics (in the sociological sense). In other words, heterodox economics can be defined in terms of what it rejects, often implying erroneously that it does not have its own body of theory and policy. If this is what heterodox economics means, as Robert Prasch (2013: 20) points out, “[a]n unfortunate, if unintended consequence, is that it reaffirms the centrality of Neoclassical Economics.” Consequently, defining and practicing heterodox economics as in opposition can lead to a self-defeating outcome.4

Insofar as the development of heterodox economics is concerned, the oppositional definition is more harmful than fruitful (this is, of course, not to suggest that the opposition to or criticism of mainstream economics is unnecessary or unimportant). There is no doubt that heterodox economists have developed their own theories and policies that are inextricably connected to the evolution of the capitalist economic system. That is, heterodox economics has and continues to develop with the evolution of the economic system as part of society; and the complexity and uncertain nature of this socio-historical evolution necessitates more than one economic perspective. As early as the 1930s, for example, institutionalists recognized their research program as ‘heterodox’ economics, which refers to “the study of economic institutions as an alternative substitute for the study of rational choice” (Ayres 1936: 234). Consider too the following statements: social economics is “a discipline studying the reciprocal relationship between economic science on the one hand and social philosophy, ethics and human dignity on the other” (Lutz 2009: 516); and “[f]eminist political economy is a counter-disciplinary approach to understanding the way in which GENDER has been culturally constructed and intertwined with the processes of CLASS formation, race and other forms of social identity to support women’s disadvantaged ...