Art Therapy at Veterans’ Administration, West Haven, Connecticut: Martha Haeseler

When I was in high school in the late 1950s, I took painting classes given by a local artist. I recall that she told us that she was holding art sessions, as a volunteer, for the “shell-shocked” veterans at the VA Medical Center in West Haven, CT. She said she enjoyed the work and found veterans very responsive and expressive in their artwork.

While I worked for many years as an art therapist on an inpatient psychiatric unit in a corporate hospital, I went to VA Connecticut Healthcare System (VACT) a few times for consultations and presentations. In 1994 I received a call from David Read Johnson, PhD, offering me a job there. My job had developed many frustrations, and I gladly accepted. I recall that my unit director at the time, who had been a unit chief at VACT, told me that I would be going from a greenhouse to a desert. I told him that I was very fond of desert plants.

David Read Johnson was a drama therapist who was widely recognized in his field. When he became unit chief on an inpatient psychiatric unit, his innovative programming, including drama, video, art, and poetry therapies, drew the attention of a new Medical Center Director, who asked him what improvements he would suggest for psychiatry. Dr. Johnson said the VA needed a Recreation and Creative Arts Therapy Section (RCATS). He was given two positions to fill, and hired a drama and an art therapist. In 1989, he became director of a newly created National Center for PTSD program, for which he hired a music therapist, pioneering the use of creative therapies for the treatment of PTSD. Currently, the National Center for PTSD includes five creative arts therapists’ positions.

In 1995, I replaced an art therapist on the inpatient neuropsychiatry unit. Within a year, I was established in an outpatient psychiatry group program called Giant Steps, and eventually became its director. Giant Steps offers art therapy and other services to between 65 and 70 veterans. After an exhibition of veterans’ art, the Honorable Rosa L. DeLauro, U.S. House of Representatives (2005), wrote to me: “It is so exciting to see that the Giant Steps Program is continuing with such great success. Beginning as only a small program at the Veteran’s Hospital, it has grown to become a model for long-term outpatient programs” (DeLauro, personal communication).

At VACT, art therapy was so valued that three of my former art therapy interns were hired for the Inpatient Psychiatry Unit, the PTSD Residential Treatment Program, and the Substance Abuse Day Program. In addition, art therapy interns do groups in the Blind Center and in the Hospice and Rehabilitation Units. We still have a drama therapist and a music therapist, and there is currently a job opening in the Cancer Care Center for a second music therapist for the VA; art therapy interns will offer groups there as well.

Although there had been no official account of art therapists employed nationally in the VA system, in 2007, when I was member of the VA National Recreation Therapy Service Advisory Board, we estimated the count to be about 18. When I left VA in January 2015, there were at least 40 accredited art therapists at VA working in positions throughout the country. VA Connecticut Healthcare System, with its large group of creative arts therapists, serves as a model for VA nationwide. My experience at VACT has shown that when an institution sees what art therapy can do, every service wants one.

The Veterans’ Administration has recently shown an interest in Complementary Alternative Therapies (CAM). Although most VA research has been directed toward the use of yoga and meditative practices, art therapy is considered a CAM. The director of one of the medical clinics at VACT hosted presentations on CAM for several years, and we creative arts therapists presented our work. This resulted in referrals beyond our capacity, and proposals to create at least one new creative therapist job. According to the US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development, “In 2011 a VA survey determines that about 9 in 10 facilities provide CAM therapies or refer patients to licensed practitioners. VA expands funding for studying complementary and alternative medicine to treat PTSD and other conditions” (US Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development, n.d.). In a 2012 survey of CAM being used in the VA National Centers for PTSD, 79 percent of residential programs and 25 percent of inpatient programs had art therapy (Libby, Pilver, & Desai, 2012, p. 1135). In a 2014 presentation, Heidi Tournoux-Hanshaw said the VA Center for Innovation wanted to see if art therapy works, and she received a grant to develop an art therapy program at the VA, Ft. Worth, TX, and at another local clinic.

A few years ago a National Initiative for Arts and Health in the Military was created. “The initiative is a collaborative effort across the military, government, private and nonprofit sectors to advance the arts and creativity for the benefit of military health” (O’Donnell, n.d). There have been three summit conferences on Advancing Research in the Arts for Health and Well-being Across the Military Continuum, which some creative therapists from VACT attended, and some funding has been made available for research (Edwards, n.d., par. 2).

So the momentum for the establishment of research networks is building and the potential for public–private partnerships is great. It is comforting to know, however, that some exciting and promising creative arts-based programs are already providing much-needed relief to our military populations and their families (Edwards, n.d. par. 8).

Although my job description as a creative arts therapist was different from that of recreation therapists, at the VA the creative arts therapists usually work within the recreation therapy service and share a federal job description. When I was on the VA Advisory Board, I suggested adding Creative Arts Therapy to the name of the National Recreation Therapy Service, but at the time this idea was not supported. At VACT, the creative arts therapists work well together with the recreation therapists; the current RCATS Chief is a recreation therapist supportive of creative arts therapy. However, at many VA Medical Centers, creative therapists are working toward having a stand-alone service or an art therapist in charge, which is a very positive move. Creative therapists at VA have their own email group, monthly calls which usually feature a clinical presentation, and have recently formed a research committee.

Figure 1.1 The garden created by veterans in the Giant Steps Program to welcome veterans and their families to the VA.

The VA’s commitment to the creative arts is shown in the National Veterans’ Creative Arts Festival, a yearly competition for veterans practicing in all branches of the creative arts. At first, I did not like the idea of competition. Then I realized that it gave all veterans a chance to have their art exhibited, seen, and taken seriously, and from that point I worked hard to help veterans who wished to enter. RCATS staff worked together to hold an annual arts expo and award ceremony at VACT. On a national level, the competition culminates in a festival to which winning veterans are invited, and every year veterans from VACT have been invited; I escorted veterans to three festivals. There are arts activities throughout the festival and a stage performance, and veterans are greatly honored for their works.

My experience at VACT was very positive. In general, I found veterans to be open to treatment and grateful for their care. I had a lot of autonomy and my ideas were welcomed, and there were means to implement them. In 1998 I wrote: “Despite the diversity in race, ethnicity and education, there is a specific VA culture, grounded in the spirit of service … and comradeship, a culture that transcends difference and provides a deep sense of identity and belonging” (Haeseler, 1998, p. 334).

In this day of the institutional revolving door and brief treatment for mental health, VA is dedicated to the lifetime treatment of the veterans in its care. VA puts veterans first, and its mission is “to fulfill President Lincoln’s promise ‘To care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan’ by serving and honoring the men and women who are America’s Veterans” (US Department of Veterans Affairs, n.d., para 1).

Art Therapy at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC: Paula Howie

For 102 years, from 1909 until 2011, Walter Reed Army Medical Center was the US Army’s flagship hospital, operating on over 113 acres in Northwest Washington, DC. The staff of the facility served more than 150,000 active and retired personnel from all branches of the military (Institute, 2009). Major Walter Reed’s (1851–1902) family donated the land on which the hospital was erected, which was then named after him. As an army physician, he led the team which confirmed that yellow fever is transmitted by mosquitoes rather than by direct contact with an infected person. In the ceremony which marked the building’s closing and move to Bethesda, General Hawley-Bowland described its medical care as being among the best in the country, particularly in the area of prosthesis (I would add in the treating of trauma) which specialties have improved significantly since the Persian Gulf War in 1991 (Tavernise, 2011).

Since the facility was legendary, its halls resounded with many famous patients. There was a room named for World War I General John J. Pershing, the only American to be promoted in his own lifetime to General of the Armies, the highest possible rank in the service (Inskeep, 2011). He lived his last years on the campus, close to his doctors. Several presidents also received medical treatment at Walter Reed, including Harry Truman and Richard Nixon (Inskeep, 2011). Eisenhower lived there for the last years of his life until his death in 1969.

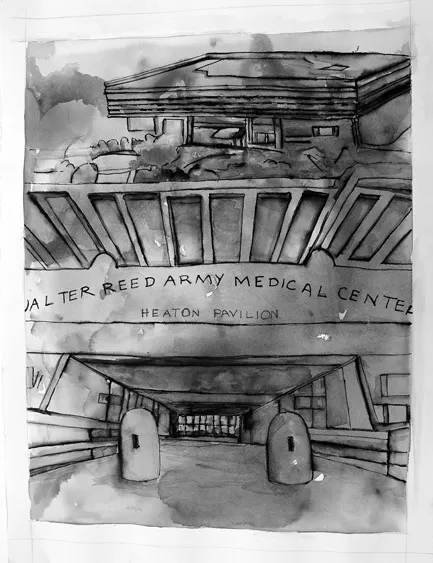

The campus included the old and new hospitals, an outpatient psychiatry building, military medical museum, civilian personnel building, restaurants and small Post Exchange (PX), and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR), among other buildings. It appears that not much thought was given to tying in the old, quaint brick façade of the original hospital built before World War I to the monolith that was the new hospital. At first glance, the exterior of the new hospital is impressive, yet overwhelmingly cold. The concrete pillars were amazing to look at, and I could imagine that when extra-terrestrials come across the ruins of our civilization eons after an apocalypse on earth, they would wonder about the civilization that could move such massive pieces of pre-stressed concrete and stone, much as we marvel at the Egyptians and the Pyramids. From the front, the building was so huge and forbidding that it was easy to fantasize adding a colorful mural to it, a rainbow, or some abstract shape to make it appear more human. In 2011, I painted a picture of the front entrance at Walter Reed, giving myself permission to add the color of my visions through a montage of angles.

Figure 1.2 Watercolor painting with pen and ink by the author, 22 × 30 inches.

In 1977, I began work as a part-time art therapist in an annexed building in the grounds of Forest Glen, Maryland. This was the temporary home of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Research. It was a charming set of buildings, which according to legend had been a hotel, a girls’ school, and a hunting lodge. It had a round building, a pagoda, a castle, a fantastic art nouveau ballroom, and many old sculptures (it has since been renovated and sold as condominiums preserving some of the original buildings). The patient areas were cloistered in the basement of some of the buildings, which had a drab, worn look to them. The art therapy offices in this annex were spacious, since old patient rooms were converted into studios. Patti Ravenscroft, ATR, MSW, a mentor and friend, began the creative arts and activities programs in 1974. She pulled together a staff of professional, dedicated, and stimulating people. When Patty left there were two full-time positions. Katherine Williams, PhD, ATR-BC, a dear colleague and later Director of the GW Graduate Art Therapy Program, was also employed in the “dungeons” of wards 106 and 110.

After a year in the annex, we moved to the main hospital in the grounds in Northwest DC. For much of the 25 years the author worked there, the hospital maintained a 1,000-bed capacity expanding to 1,200 beds during the First Gulf War, finally downsizing to fewer than 500 beds in 2002. Every evening there was a ceremony at the retiring of the colors complete with taps and firing of 21 blank rounds. There was a small orange flag on the rooftop used by helicopter pilots to ascertain wind directions when landing on the helipad beside the hospital. The move to the main campus was definitely a boon to the patients who got rooms with window views. At one point, the art therapy staff had eight full-time positions. For patients who had privileges to leave the ward, we also ran groups in our own art studio on another ward.

Art therapy, being a relatively young profession (the George Washington University program began in 1971 and was one of a handful of graduate-level training programs in the country) and not being a military specialty, was not planned for in this monolithic new building. We moved from floor to floor and office to office until, in the 1990s, a studio was built for us using part of the dayroom on ward 52. The studio had a large space for meeting with groups or individuals, storage, a two-way mirror for training purposes (there were at least four students assigned to the program in a given semester), and a kiln room for firing clay pieces (See photo of the studio in Figure 3.3). The hospital underwent many modifications as the beginnings of base realignment and downsizing took its toll on clinical staff and patient census. The closure of Walter Reed and the move to Bethesda was intended to reduce the number of facilities in the area in order to better fit the military’s needs. At its closing in 2011, Walter Reed had retained only 150 inpatient beds.

Walter Reed was a longer term facility for those who were stabilized at the front but who needed further treatment (it was called a tertiary care facility because we saw people who were cared for at the site of their injuries and in a hospital theater before coming to WR). There were five such medical centers in the country but none of the others employed art therapists when the program began at Walter Reed. Although housing many medical specialties, Psychiatry was the largest service in the hospital and included outpatient, child and adolescent, partial hospital, consultation/liaison, and inpatient services. The latter had a capacity of 120 inpatient beds or three 40-bed wards. The Psychiatry service offered comprehensive mental health services that included art, recre...