Across a variety of fields, the relationship between research and practice is often complementary but not integrated. Since the early 1980s there has been a call for increased collaboration between research and clinical scholars (Singer, 1980). Both those discussing individual treatment and systemic therapies have articulated a vision in which therapy is best situated on the solid foundation of research (Lebow, 1988). Vivian et al. (2012) emphasized researchers must inform clinicians of evidence and clinicians must communicate to researchers their observations. Some journals explicitly include this in their mission statements, and some scholars actively engage in both practices. However, integration still rarely occurs. Those who engage in both often state it is like tapping into “both sides” of their brains. Stricker and Keisner (1985) articulated this idea by suggesting that the thought-process involved in research is analytical whereas the clinician highlights a creative integration.

Following the many voices that have suggested the integration of research and practice is worthwhile, the challenge remains to establish a format that bridges both perspectives and provides mutual benefit. Too often, exchanges between researchers and clinicians are unsatisfying for one or both. An ongoing and mutually beneficial exchange is extremely rare, and when this occurs it likely was facilitated, at least in part, by an ability to coalesce around a single mutual goal. We speculate the goal of helping others (why most of us go into the related fields) is a powerful unifying force that can bridge research and practice. Achieving commitment to doing so may be the more difficult task, given often-competing job demands and roles. Even when researchers graciously provide findings that assist clinicians in forming a foundation for their work, these researchers often feel that clinicians cherry-pick only the findings that support their clinical hunches (Ganong & Coleman, 1986). At the same time, we do observe (anecdotally) that newer generations of research and clinical scholars seem more interested in building bridges.

The current book continues the method established by Browning and Pasley (2015) in Contemporary Families: Translating Research into Practice. Although the family types examined here are new and the method of integration slightly revised, the primary process remains. In order to create a central unifying focus, a case study guided the work of both research and clinical scholars. The term research scholars is used to refer to those authors who are established experts in their subfields, whereas clinical scholars is used to refer to those authors who are established experts for whom the merging of clinical theory and practice represents their professional identity. In some cases, scholars have some expertise across both areas. It is hoped that a wide range of those interested in both the research findings and clinical practice with families will find this book captivating, informative, and useful. Case studies and genograms in this volume have been moved to the front of each integrated chapter. These are followed by a research and a clinical section that, together, use evidence to inform practice.

Creating a Verifiable Clinical Practice With a Diverse Population

Although the argument has been made (Browning & Pasley, 2015) that relying entirely on evidence-based practice (EBP) is too narrow and prescribed given the great variation in contemporary families, it would be naïve to ignore the benefits of culling useful interventions. No specific EBP is designed for the families discussed in this volume; however, each practice offers a coherent and supported approach to treating a clearly delineated population. If one were to separate EBPs into two categories, they could be labeled “diagnostic-centered” and “systemic.” The diagnostic-centered therapies address an individual and the specific diagnosis (e.g., anxiety) that the treatment is designed to ameliorate. Systemic treatments seek to improve family functioning, but can focus on problems that may be individual (such as an adolescent’s drug abuse). Both general categories rely on an understanding of the population in question, some component of Common Factors (e.g., empathy, alliance, and goal setting), and a specific intervention. We acknowledge these treatment recipes (treatments delineated in specific steps) do assist clinicians. However, they do not form a complete treatment.

An example of a “gold standard” EBP from the diagnosis-centered treatment is dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan & Dexter-Mazza, 2008). Following the recipe reveals that the primary features of borderline personality disorder are defined so that the practitioner can tailor the approach, thus avoiding mistakes that occur when these symptoms are poorly understood. The approach combines an understanding of emotional regulation, interpersonal systems, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and strategic interventions. Next, the common factors of alliance, goal setting, and safety are added to create a sophisticated and effective approach.

A “gold standard” systemic approach, such as emotionally focused therapy (EFT; Johnson, 2004), creates a clear delineation of the way attachment needs are presented in couple interactions. Johnson’s approach addresses the rigid, constricted interactional patterns that lead to attacks, withdrawal, and disassociation—common problems in distressed couples. Thus, EFT assists people in identifying the pattern such that they can curtail attacks on each other. The goal of this approach is to increase safety and security so that couples can again trust each other. These interventions solidify this work by pushing the clinician to remain steadfastly present in the emotional experience of the couples’ attachment needs.

This brief summary is not intended to lessen the importance of these approaches; rather, it is profoundly useful to examine the steps that make these targeted approaches effective. By understanding these treatments, practitioners can increase their therapeutic effectiveness regardless of the clinical diversity they face. It is in this process that the integration of research and practice is particularly useful, especially when the clinical target is more complex. Certainly, a contemporary family (e.g., a family of homicide) may have members that greatly benefit from a targeted EBP. For example, a family may arrive for treatment following the murder of a 22-year-old son. The mother’s recent agoraphobia may be best addressed partially with exposure-based cognitive therapy.

Make no mistake, when one can find a specific EBP tailored to the presenting problem, it is always worth understanding how that approach is effective. However, when the complexity of the case demands a more variegated procedure, one shifts from EBP to ESP (evidence-supported practice), such as the approaches described in this volume. One could argue that the ESP approach to creating practice models is ideally suited to cases with a high level of complexity, and we believe that today’s families exhibit such a level. What makes an ESP distinct is that by using the research-supported common factors of psychotherapy and relying on the extant research literature describing the specific needs of particular families, therapy can both benefit from the traditional EBP approaches and extend to properly address the complexity.

Social psychologists have suggested researchers are participant-observers in their research. Beyond the idea that true objectivity in psychological research is elusive, psychological concepts are ephemeral. In some instances objectivity may not even be desired. As Stricker and Keisner (1985) stated, clinicians made “dubious assumptions… that research represents an objective approval to understanding human activity whereas clinical inquiry is based on a subjective model” (p. 10). Connecting research and practice relies on assisting clinicians to see the “objectivity” of their work, and for researchers to recognize the subjectivity of their work. Stated another way, bridging this gap requires we break down the underlying erroneous dichotomy of objective-subjective and see the gray space between.

Given this understanding about research and therapy, it is useful to understand further the relationship between EBP (evidence-based practice) and ESP (evidence-supported practice).

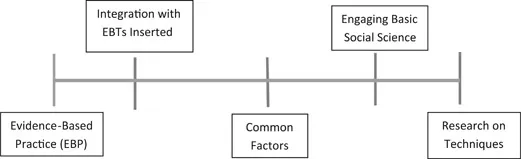

All approaches that fall within this spectrum (see Figure 1.1) have adherents who prefer one model over the other. Evidence-based practice receives the greatest respect from insurance companies and government-sponsored grants. However, legions of scholars, practitioners, and agencies recognize the importance of widening the range of treatment options given the complexity of the human condition. Most approaches considered ESPs combine two or more of the categories in Figure 1.1. In other words, many practicing therapists utilize one evidence-based treatment (EBT), but for many clients they have preferred techniques, or they emphasize common factors. Such integration is increasingly common in the United States, whereas some countries (e.g., Italy) tend to encourage clinicians to adhere to a single theoretical approach. In addition to simple integration (combining two approaches), some models are bringing multiple pieces together by including some aspects of specific EBT approaches with other components not formally validated.

Figure 1.1 Spectrum of Therapeutic Outcome Validation

Research into specific clinical techniques suggests that reliance on these techniques may be less useful than people suspect. Specific treatments independently account for (at most) 10% of positive treatment outcomes (Castonguay & Beutler, 2006). Given the “close to 150 different models to treatment that are effective” (p. 632), it is sensible to approach successful therapeutic outcome as a thoughtful integration of specific techniques, a positive therapeutic alliance, and client factors. Further, in a recent review of meta-analyses, it was reaffirmed that most active psychotherapeutic treatments produce approximately the same outcome (Luborsky et al., 2002). In a meta-analytic review of treatment component studies, Ahn and Wampold (2001) found that treatment with a specific intervention was no more effective than treatment without the specific intervention component. At a minimum, the importance of factors common to all therapies such as the therapeutic relationship, client/therapist factors, and the placebo effect must be respected in both research and practice.

This book represents a focused attempt to establish a class of clinical approaches supported by basic social science research. Nonclinical research or basic research is “directed at the understanding of people, rather than the means of intervening with them” (Cohen, 1979, p. 7). The question becomes, “Exactly how is research informing practice?” This is a critical issue because an unskilled clinician could slip into the ESP umbrella within this category. Therefore, it is incumbent upon the clinician who is using these approaches to be conversant with the relevant research. This is a critical caveat, “the relevant research,” since most clinicians, even at the doctoral level, drift rapidly away from reading research after graduating. Even those who enjoyed research tend to drop down to reading a couple studies a month (Cohen, 1979). Further, clinicians admit to a significant preference for consulting with colleagues when bewildered by a case rather than looking to the extant literature for answers.

For this interaction of research and practice to succeed, clinicians need to update their knowledge as the science reveals new material, but also, researchers must point out information that appears clinically relevant. Keeping researchers interested in clinical scholarship is more difficult. Except for those researchers who engage in clinical practice, researchers are not even advised to examine the clinical literature. Clinical scholars could improve their exchange by articulating questions that researchers could pursue.

Seven Contemporary Families

The family types considered in this volume have no single commonality. They are defined rather by the fact that they fall outside the increasingly rare delineation of “typical families.” The same determination was made in selecting the family types examined in Contemporary Families: Translating Research into Practice (Browning & Pasley, 2015). In that volume the families studied were: (1) families of adoption; (2) families of autism; (3) interracial families; (4) grandparent-headed families; (5) foster families; (6) LGBTQ families; and (7) families of chronic illness. This volume selected seven different families: (1) families of divorce; (2) stepfamilies; (3) “fragile families”; (4) families of addiction; (5) families of homicide; (6) families post-imprisonment; and (7) cyberbullied families. In addition to being complex systems, each of these family types has certain impediments that affect clinical progress when they seek treatment.

Divorced families predominantly exist within a context of conflict. In a divorce, at least one partner is seeking to end the current status quo of the family. There is virtually always someone left hurt and angry. Because these families also lead to a new residence for certain members, issues of familial connection, affection, finance, and communication are invariably raised. This is a potentially difficult population because permission for treatment may be withheld by parents who are angry at a former spouse. A parent (with shared legal custody) cannot bring his or her own child to treatment without the other parent’s permission. This type of behavior is usually justified by anger and hurt. Therapists can intervene and attempt to present a position in which the child will benefit, but numerous reasons may be used to justify not allowing a child in treatment.

Stepfamilies are distinct from first-union families, yet by outside appearances can look identical, and that perceptual appearance is one of the challenges for these families. The stepfamily should not be considered the same as a first-union family, and this error often sabotages treatment when the clinician is naïve to these differences. The stepfamily consists of some people who barely know each other, yet are living in intimate proximity and often vying for reassurance of connection with old and new stepfamily members. The stepfamily often is surprised by the emotional volatility within the home shortly after the union, whether that be marriage or cohabitation.

The “Fragile Family” is an amorphous system. It has few consistencies, ...