![]()

Chapter 1

The History of Gum Printing

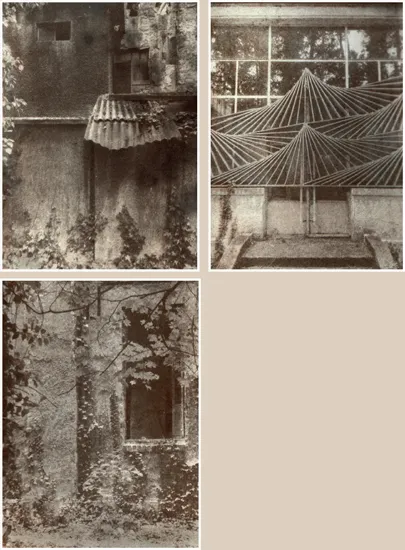

Figures 1.1–1.3. Jardin d’Agronomie Tropical, duo-tone gum bichromate with handmade pigments © John Brewer 2015. “These images are taken with an iPhone in Jardin d’Agronomie Tropical near Paris, a dilapidated collection of buildings from France’s dark past. This small park hosted the 1907 Paris Colonial Exposition. The exhibition was based around several villages representing the French empire (Indochine, Madagascar, Congo, Sudan, Tunisia, Morocco). Inhabitants from these territories were also brought over to live in these villages and be observed by curious visitors for the duration of the exhibition, a sort of human zoo. With this body of work I have used two pigments I have made from materials found in France, charcoal from burnt trees and a brown/ochre from Roussillon.”

John Brewer (Manchester, UK) first became interested in photography in the 1970s and is both self taught and formally educated. Brewer’s work has been published, exhibited, and resides in private collections internationally. His primary interest is historic photographic processes. Brewer teaches regularly in the UK and the South of France. To see more of his work, visit thevictorianphotographer.com or johnbrewerphotography.com.

Figure 1.4. Great Catch, © Christina Z. Anderson. From left to right: original slide image; the image exposed in plain gum arabic just after exposure and before development; the image after development that has cleared to a pale, sage green; the image left out in sunlight for a couple hours with a circular glass on top. Sunlight fades the dichromate green color to an even paler, almost imperceptible gray-green. By contrast, where the glass has prevented the sunlight from hitting the print, the yellow circle remaining needs more time to fade, which it will with time and in regular room light. This illustrates the necessity of adding pigment to the gum layer, something that wasn’t suggested until 16 years after the discovery of dichromate sensitivity! Otherwise there will hardly be an image left after a few days.

Gum printing is a 19th century photographic process wherein a mixture of gum arabic, photo-sensitive dichromate, and watercolor pigment is brushed on paper, dried, and exposed to light under a large negative. The light-sensitive dichromate hardens the gum arabic proportionately to the amount of light received. With a simple water development, the unhardened parts of the gum layer wash away and voilà—a positive image of the negative is revealed.

Gum arabic is only one of a number of colloids that dichromates will harden—for example, egg whites, gelatin, or casein—hence the name gum printing or gum bichromate. The correct scientific term is actually gum dichromate but for some reason the bichromate term continues to be used in an endearing and historical, albeit incorrect, way.

The watercolor pigment is added to the layer to make the hardened layer colored and visible. If watercolor were not added, the hardened gum layer would start out as a brownish-yellow image that, over time, fades to a barely imperceptible green. When gum printing first started, practitioners used various earth tones such as black, brown, ochre, and sienna to create monochromatic or duotone images. Today, gum is infinitely more colorful.

Gum is 100% archival, the most of any photographic process. A darkroom is not necessary: the entire process can be carried out in regular room light, what we nowadays call a “dimroom.” It is cheap; after the initial expense of setting up a dimroom, a gum print doesn’t cost much more than the paper it is printed on. It is the most painterly photographic process there is, and can be as far removed from, or as close to, a photograph as desired. It produces one-of-a-kind prints. And it is for those of us who appreciate the journey as much as the destination, the process as much as the end product.

Crash course in gum history

There is a certain pleasure in realizing one’s connectedness to the very beginning of photography when doing the gum process. A brief timeline follows, highlighting some of gum’s key players. For a more detailed time line, see Gum Printing and Other Amazing Contact Printing Processes.

Figure 1.5. Boat, Scottish Loch, monochrome gum bichromate © Johnny Brian 2014. Brian’s photograph is poignant for several reasons. One, it is photographed in Scotland, birthplace of Mungo Ponton who made the first dichromate photograms in 1839. Two, it is a monochrome gum similar to those that would have been created at gum’s dawning, although Brian printed his monochrome gum in multiple layers, a technique that wasn’t discovered until decades later. Three, it references a very famous image by Peter Henry Emerson, Gathering Water Lilies (1886), but Brian’s boat is empty of people and his somewhat-Pictorialist-romantic aesthetic has a contemporary melancholy which is so prevalent today.

In 1798 French chemist Louis Nicolas Vauquelin discovered the light sensitivity of chromium and chromic acid.1

In 1832 Gustav Suckow discovered potassium bichromate in contact with organic matter is reduced by light and takes on a green color.2

In 1839 Scotsman Mungo Ponton made the first dichromate photograms by placing objects on top of dichromated paper and exposing the paper to light. He was pretty excited because it resulted in a yellow to orange to brown image, but as my visual Great Catch shows, this dichromate “stain” will fade to a pale green with time.3

In 1840 Edmund Becquerel discovered it was the sizing of the paper that had an effect on dichromate’s sensitivity to light, which was the beginning of the discovery that dichromates harden colloids.4 Even though two sources say Becquerel found that dichromates harden organics, too, Fox Talbot gets credit for it. Ponton did not discover that dichromates hardened colloids.5

In 1852 William Henry Fox Talbot discovered dichromate would harden gelatin and he took out a patent in “photoglyphy” in 1853.6

In 1855 August 27 French patent no. 24,592 and December 13 English patent No. 2815, Alphonse-Louis Poitevin (1819-1882) adds pigment to the colloid and dichromate, and forever becomes the historical father of gum.7

In 1858 April 10 John Pouncy filed patent no. 780 in England entitled “Improvements in the Production of Photographic Pictures,” a pigmented gum process.8 Unfortunately Poitevin’s patent of 1855 already specified colloids of which gum is one (though there is no evidence that Poitevin used gum). Pouncy withdrew his patent9 and Poitevin remains the father of gum and France the country of gum’s origin.

The concept of multiple layer printing would not be discovered for almost 40 years. Gum was done with one thick highly pigmented layer, with probably bullet-proof film negatives, and out in the sunlight. Thus success with a short-scale, contrasty process such as gum (called carbon printing at this time) was difficult, compounded with such a thick layer, and the resulting prints were flaky and grainy with no halftones (what we term midtones today). Prints were described as soot and chalk. Human nature is to blame the process and not the practice and that’s what happened. The myth that gum could not do halftones was heard far and wide, even though it is recorded in the journals that Pouncy had produced results hardly distinguishable from silver prints.10 Some people even accused Pouncy of producing prints by means which he had not disclosed.11, 12

That same year it was announced that Pouncy along with Poitevin and others won the Duc de Luynes prize for a process that improved image permanence. Poitevin got the gold medal (600 francs) for priority of invention of the carbon process, and Pouncy—who was the first to supply the French Commission with pure carbon prints—the silver (400 francs).13

1864 Joseph Wilson Swan introduced carbon transfer in which a layer of pigmented gelatin was transferred to another support in development. Halftones were beautifully rendered in this process and gum was put on the back burner for 3 decades.14 Poor gum; it came at a time when sharpness and detail were of utmost importance.15 Swan’s new process was both archival and detailed. Commercial carbon papers such as produced by the Autotype company came on the market and gum couldn’t compete.

In 1890 an interesting set of articles on Impressionism appeared in the British Journal of Photography (BJP) during the next several years.16 Photographic change was in the air.

In 1891–2 George Davison, Maskell, and others seceded from the...