![]() PART I

PART I![]()

1

DISCURSIVE PLANS

Conceiving Planning Ideas

The conviction that we can build better places is a powerful one. It not only motivates various actors—such as residents, homeowners and officials—to anticipate and improve existing urban conditions, it also catalyzes the conception and adoption of formal urban plans. Central to the development of twentieth-century planning thought and practice is the view that professionally prepared plans can help guide progressive efforts to provide improved amenities, mobility and propriety, helping to bridge many historical divisions, regional differences and social challenges.1 Exemplifying this approach, planners have employed the idea of the neighborhood unit in diverse contexts, including the United Kingdom, United States, Ghana, India and China.2

In the first part of this chapter, I describe the American social anxieties, theoretical influences and practical concerns that shaped the origin of the idea of the neighborhood unit in the 1920s. My aim is to explain the manner in which the contemporary reformist movement influenced the neighborhood unit’s conceptualization as a physical planning instrument intended to address a particular set of urban and social concerns. Combining a description of physical features with an account of social meaning tied to place, the concept posits that a specific kind of layout will generate proximate social effects. In the second part of this chapter, I describe the concept’s introduction to India. Here, my objective is to highlight a different set of concerns, such as national development and modernization, which underpinned pioneering planners’ belief that the neighborhood unit suited the Indian context, just as well as it suited the American context.

By explaining how planners modified and repositioned the discursive concept in line with their comprehension of the local context, I highlight how the neighborhood unit’s meaning and purpose in India was markedly different from that in the United States. But, not discounting the importance of clients’ cultural preferences and practical requirements, the idea ultimately symbolized progressive impulses in both places. When seen through this lens, the presumed “universal” significance of the notion of a well-provisioned, place-based community was in itself the most significant attribute of the neighborhood unit concept.

Clarence Perry and the Neighborhood Unit

The origin and applications of the neighborhood unit concept are well documented.3 In this section, my focus is on highlighting the influence of the contemporary American context on the conception of the neighborhood unit. The expression “neighborhood unit” was first employed by New York planner Clarence Perry in the 1920s to refer to his proposed physical planning concept for designing neighborhoods. In suggesting this concept, Perry drew upon several sources of knowledge, such as his own professional and personal experiences, recent theoretical advancements and his association with other like-minded individuals concerned with the design and planning of cities. An understanding of these influences is important, because it helps us comprehend how the social and civic concerns of the times served as a wellspring for Perry’s imagination.

Clarence Perry spent most of his professional life at the Russell Sage Foundation in New York, where he worked from 1909 to 1937. The Sage Foundation was a leading philanthropic organization of the time, founded in 1907 to work in the areas of social and civic reforms. Concerns about how to improve American urban communities were emerging in contemporary social sciences and the humanities, motivating turn-of-the-century reformist thinking. For example, the American intellectual elites were concerned that the speeding up of urbanization ruptured the traditional ties between the individual, household and place. While some commentators were deeply pessimistic about the future of modern cities (for example, White and White 1962), some reformists approached the developing metropolis with a combination of pragmatism and optimism, believing that a restoration of the links between family, neighborhood and community might offer a possible solution. Jane Addams, who founded a settlement house, and the influential pragmatic philosopher John Dewey subscribed to this view. The basic tenet of these social reformers was not to defy or ignore the city but to work toward promoting community and social communication, and inculcating neighborliness in the seemingly inchoate and hostile urban environment.4

These concerns were probably best articulated in the literature that came out of the new field of urban sociology. Louis Wirth, the Chicago School sociologist, laid out the primary characteristics of the contemporary metropolis in his seminal essay Urbanism as a Way of Life (1938). Here the grimmer side of his argument raised the specters of “anomie” and “alienation” in an imagined “mass society,” and the brighter side evoked the prospect of a new, progressive era of urbanity, tolerance and cosmopolitanism. Perry was exposed to this emerging literature, and at various times in his career acknowledged the influence of Professors Charles Cooley, Robert Park and Herbert Miller, who emphasized the importance of neighborhood institutions to social welfare.5 In his 1909 book Social Organization, Cooley argued that neighborhoods were the nurseries of “primary ideals,” which he identified as loyalty, truth, service and kindness. Park and Miller’s works were underpinned by similar concerns and influenced Perry:

It is only in an organized group—in the home, the neighborhood, the trade union, the co-operative society—where he is a power and an influence, in some region where he has a status and represents something, that man can maintain a stable responsibility. There is only one kind of neighborhood having no representative citizen … the slum; a world where men cease to be persons because they represent nothing.6

Such influences catalyzed Perry’s belief that in ever-growing and increasingly differentiated cities, citizens needed a comprehensible and accessible focal point, such as a neighborhood school, around which to base their daily activities. He also imagined that the school’s centrality would be further strengthened if the neighborhood, with the school at its heart, became the basic unit for planning, and if the logical definition for a neighborhood derived from the distance a child could easily walk to school.

A second set of influences on the neighborhood unit concept came from Perry’s interest in physical planning. He lived in the planned community of Forest Hills Gardens, a spacious suburban development sponsored by the Sage Foundation, and subscribed to the prevalent notion that physical changes in the urban fabric could improve social life and enhance the spirit of citizenship. In advocating the use of neighborhood schools as a focal point to foster a spirit of civic community, Perry was also influenced by the 1907 St. Louis Plan.7 This was one of many plans prepared following the Columbian Exposition of 1893, most of which copied the “city beautiful” ideas of the Burnham Plan of Chicago in their focus on centralized civic centers.8 The St. Louis Plan, however, was unique in that it suggested the construction of half a dozen civic centers in different parts of the city. These civic centers were envisaged as a combination of facilities around a common center, such as a park.

In addition to his personal experiences and exposure to recent theoretical advancement, a third distinctive set of influences shaped Perry’s imagination: interactions and collaborations with other like-minded individuals who were concerned with the design and planning of cities. Perry’s technical milieu provided him with an opportunity not only to learn from other scholars and professionals but also to showcase his work within diverse institutional networks. For instance, Perry collaborated with Clarence Stein and Henry Wright in the design of the planned community of Radburn.9 He also worked as a team member of the Regional Plan Association of America (RPAA) alongside Lewis Mumford and Catherine Bauer, who had written in support of the neighborhood unit concept.10 Additionally, Perry’s presentations in a variety of institutional settings helped him accommodate wider concerns into his argument in favor of neighborhood units. Perry presented the outlines of his concept, tentatively named the “community unit,” at the National Conference of Social Work in 1924, where he argued that the neighborhood:

With its physical demarcation, its planned recreational facilities, its accessible shopping centers, and its convenient circulatory system—all integrated and harmonized by artistic designing—would furnish the kind of environment where vigorous health, a rich social life, civic efficiency, and a progressive community consciousness would spontaneously develop and permanently flourish.11

Here, Perry explicitly linked the contemporary social concerns that preoccupied his audience with spatial means that could address those concerns, in accordance with the popular belief that appropriate urban planning could reinvigorate and sustain the links between the individual, family and community. He was also offering a unique imagined program for how those relationships could be restored in practice, through place-based features such as distinct neighborhood boundaries, road networks and parks. These initial arguments, in an improved format and accommodating a broader range of concerns, matured into the neighborhood unit concept, which Perry presented in the Regional Survey of New York and its Environs in 1929.

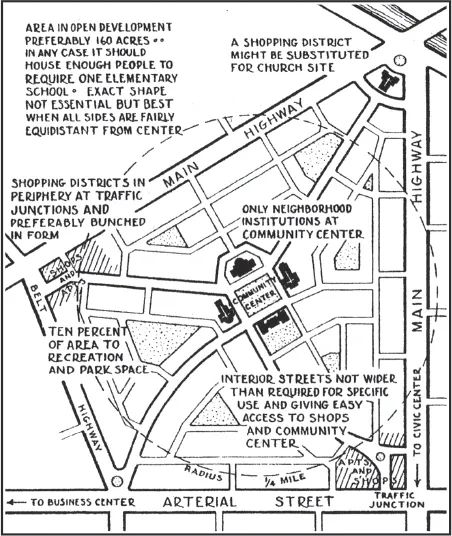

As evident in Figure 1.1, Perry’s proposal for the neighborhood unit was strictly residential in character, in line with the zoning principle, and pivoted around a centrally placed community open space that reinforced civic pride because it contained the school. The public school was, he wrote, in a real sense “a civic institution.” He went on, “It flies the national flag … is found in every local community … and deserves a dignified site.”12 Along with the school, which occupied the heart of the neighborhood unit, Perry’s concept contained three other basic design elements: small parks and playgrounds, small stores and a hierarchal configuration of streets that allowed all public facilities to be accessed safely by pedestrians. To define the relationship between these design elements, Perry prescribed six simple planning principles in detail:

• Size: a residential unit development should provide housing for that population for which one elementary school is ordinarily required, its actual area depending upon population density.

• Boundaries: the unit should be bounded on all sides by arterial streets, sufficiently wide to facilitate bypassing through traffic.

• Open spaces: a system of small parks and recreation spaces, planned to meet the needs of the particular neighborhood, should be provided.

• Institution site: sites for the school and other institutions having service spheres coinciding with the limits of the units should be suitably grouped about a central point.

• Local shops: one or more shopping districts, adequate for the population to be served, should be laid out in the circumference of the unit, preferably at traffic junctions and adjacent to similar districts of adjoining neighborhoods.

• Internal street system: the unit should be provided with a special street system, each highway being proportioned to its probable traffic load, and the street net as a whole being designed to facilitate circulation within the unit and to discourage its use by through traffic.13

FIGURE 1.1 Clarence Perry’s neighborhood unit concept

Source: Perry, C. 1929. Regional Survey of New York and...