- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Naturalism

About this book

Many contemporary Anglo-American philosophers describe themselves as naturalists. But what do they mean by that term? Popular naturalist slogans like, "there is no first philosophy" or "philosophy is continuous with the natural sciences" are far from illuminating. "Understanding Naturalism" provides a clear and readable survey of the main strands in recent naturalist thought. The origin and development of naturalist ideas in epistemology, metaphysics and semantics is explained through the works of Quine, Goldman, Kuhn, Chalmers, Papineau, Millikan and others. The most common objections to the naturalist project - that it involves a change of subject and fails to engage with "real" philosophical problems, that it is self-refuting, and that naturalism cannot deal with normative notions like truth, justification and meaning - are all discussed. "Understanding Naturalism" distinguishes two strands of naturalist thinking - the constructive and the deflationary - and explains how this distinction can invigorate naturalism and the future of philosophical research.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & Theoryone

First philosophy

One of the slogans of naturalism mentioned in the introduction is that "there is no first philosophy". In this chapter we shall try to make sense of the idea of first philosophy - what it is and why many philosophers have thought we needed such a thing. What follows is a potted history of first philosophies - enough for us to understand both the motivations for first philosophy and to highlight some of the problems that cause naturalists to reject the very idea.

A first philosophical problem: scepticism

One philosopher proclaiming precisely that he is undertaking first philosophy is Rene Descartes. The full title of Descartes's most celebrated work is Meditations on First Philosophy. Descartes's aim is to rebuild our knowledge on solid foundations. He begins in a negative mode; and it is the negative aspect of Descartes's philosophy that will concern us here. He starts by questioning on what basis we can claim to know anything.

For certain cases answers readily present themselves. For example, I know that I am sitting at my desk right now with my laptop in front of me because I can see my desk, my laptop and my hands moving over the keyboard. That seems like a very good answer to the question: how do you know that you are now sitting at your desk typing on your laptop?

Descartes proceeds in the First Meditation to offer us reasons to doubt the adequacy of the simple idea that we know things about the world by looking, touching and using our other senses. First Descartes points out that the senses often deceive us. Sticks that we know are straight look bent when half-submerged in water. So we cannot always trust what we see. Most of us are not likely to be impressed by this argument for doubting what we sense since we know that the stick is really straight only because we can feel it. We need to use information from our other senses, in this case the sense of touch, to see that we have made a mistake. Descartes agrees and quickly moves on to provide other more substantial reasons for doubting what we see. Could it not be the case that, even though I think I am sitting here writing, I might really be dreaming? After all, I would have exactly the same sensations I have now but I would not in fact be sitting at my desk writing this book.

In the final few paragraphs of the First Meditation Descartes provides another, very striking tale which casts doubt on everything we think we know:

I will suppose ... some malicious demon of the utmost power and cunning has employed all his energies in order to deceive me. I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely the delusions of dreams which he has devised to ensnare my judgement.

(Descartes 1641: 22-3)

Many contemporary philosophers, less enamoured of talk of demons, offer alternative tales. How do we know that we are not just a brain-in-a-vat with a mad scientist manipulating everything we think we see and feel? How do we know that we are not like the many human beings in the film The Matrix, human batteries, which are fed images of the world that are nothing like the dark and terrible reality?

The upshot of all these stories is the same. We do not really know for certain anything about the world around us. All we actually know are our own thoughts. I do not doubt, I cannot doubt, that I think I am writing. But I do not know for certain that is how things really are.

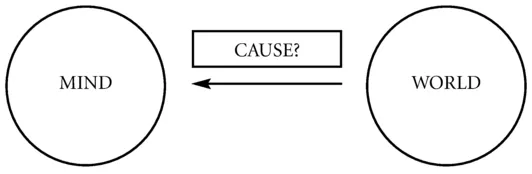

Descartes's understanding of the relation of our ideas to the world beyond us can be pictured as in Figure 1.1. On one side we have the contents of our minds, our ideas. On the other side we have the world beyond us. We think that the cause of many of our ideas is something external to us - like laptops and desks. But when we reflect, we realize that things other than those objects might cause the same ideas. Maybe I am dreaming so I am the cause of those ideas, or maybe I am being deceived by some external agent so she is the cause of those ideas. Knowledge of the external world, in Descartes's picture, is mediated by ideas. Once we admit this, we have a worry about whether the cause of those ideas is really what we ordinarily take it to be. We have to worry about whether my representation of reality is anything like the way the world really is. This is what philosophers refer to as the problem of scepticism.

Figure 1.1 Descartes's view of the relation of ideas to the world

Descartes's own solution is famously unsatisfactory. He proves the existence of a God by starting from his idea of God. Since God is a non-deceiver, we are guaranteed not to be systematically mistaken about the world. We do not need to go into the details of Descartes's proof and its problems. (See Cottingham 1986 and Williams 1978 for a detailed and clear discussion.) Suffice to say that, had Descartes really been able to prove the existence of God he would be a far more famous philosopher than he already is.

Despite the failure of his solution to the problem of scepticism, Descartes presents in a vivid way a very general problem about our knowledge: how can we be sure that we know anything at all? Importantly, the way that he has done this makes it clear that it is the sort of question only a philosopher could answer. If a scientist tried to explain how I know about the objects in front of me and began talking about light reflecting off the surface of the laptop, which is then focused onto my retina by the lens of my eye (among other things), where it is converted into an electric signal and sent via the optic nerve to my brain, and so on - however full and complete that answer seemed, it would not answer Descartes's worry. If we take Descartes seriously, we cannot be certain that any of those objects referred to in the scientist's explanation exist. So we cannot use them to answer Descartes's question.

Here, then, is a problem that sets philosophy radically apart from science. It is also a problem that we must answer before we can place full trust in the results of any science. If we are worried about our knowledge of anything and everything, then all our scientific knowledge must be in question too. We can see the sense in calling this first philosophy. Until this philosophical question is answered we cannot claim knowledge of anything.

Another first philosophical problem: induction

The problem of scepticism calls all our beliefs into doubt. Another more modest form of scepticism, most vividly presented by the great Scottish philosopher, David Hume, raises doubts about the legitimacy of our scientific knowledge.

Scientific theories make predictions about how things will turn out in the future. Astronomers, for example, predict that there will be a total solar eclipse visible over the UK and Ireland on 23 September 2090. Less exactly, but perhaps more importantly, doctors predict that smokers are likely to die younger than non-smokers.

Simplifying somewhat, science can do this because scientists discover laws or regularities in nature that are the basis of this prediction. Here is a very crude version of the sort of inference a scientist makes: every morning I get up and I see the sun rise, so I conclude that the sun will rise every morning. My inference starts with some claims about how things have been in the past and then makes a prediction about how things will turn out in the future. Similarly, when a drug goes through clinical trials and is declared safe for human consumption, the same sort of inference has taken place. Because the drug was shown not to cause harmful side-effects on our trial patients, we can conclude that future patients who use this drug will not suffer any adverse side-effects either. We call such inferences, which go from how things have been in the past to how things will turn out in the future, inductions; and in all such arguments we must assume that how things have gone in the past is an indication of how things will turn out in the future.

The first problem with an inductive argument is, as Hume points out, that its conclusion is not guaranteed to be true. "That there is no demonstrative argument in this case seems evident; since it implies no contradiction that the course of nature may change" (Hume 1748: 35). In other words, everything we know about the past may be true and yet it would be quite consistent for the world to behave differently tomorrow; for the sun not to rise or new patients who took the drug in question to start having severe allergic reactions. The idea that the future will resemble the past is not a logical truth.

This seems undeniable but perhaps not very worrying. Even if what we learn from the past does not guarantee that the future will turn out as we predict, it at least, we might think, makes it probable. Hume rejects this too. He wrote that we cannot "so much as prove by any probable arguments that the future must be conformable to the past" (Hume 1740).

Consider a simple case of something we know to be probable. When we roll a fair die we believe that there is an equal chance that it will land on any side. So it is very probable that we will not roll a 6. But how do we know that in the future rolls of the die will conform to the pattern described here, so that throws of 6's are relatively improbable. Well, we might appeal to our knowledge of the mathematics of probability. Given that we assume an equal probability that any side might turn up, it is far more probable that we shall roll a number between 1 and 5 than a 6. This is, as it stands, a truism. It follows simply from the way we have fixed the probabilities in this case. The real question is why we should believe that the probability of any side landing face up is the same for each side. No formal mathematical theory can tell us why because formal theories do not, by themselves, say anything about real objects. One obvious response is that our knowledge that the die is fair is based on experience. We might have rolled the die thousands of times and found that, roughly speaking, each side came up equally frequently. But to use this evidence for future rolls of the die we would have to assume that the future resembles the past - which is precisely the claim that we are looking to justify.

To make sense of the claim that something is probable you need to assume that the event in question conforms to some pattern, a pattern in which events of that type occur more often than not. But even if events in the past have conformed to that pattern, that gives no reason to assume that events in the future will continue to do so. Just as it is logically possible that the sun will not rise, it is also possible that a die that used to be fair will suddenly start to become biased so that every time we throw it in the future it turns up a 6.

Inductions, whether we use probatalilies or not, require us to assume that the future is in some way like the past. Hume has shown us that we have no way of demonstrating that this is the case. Nevertheless, we might think that even if we cannot demonstrate that the future will be like the past, we have very good reasons for believing it. My experience teaches me that the future resembles the past. For example, last week I made the prediction that the sun would indeed rise in the east and today, lo and behold, it did. So it turned out that I was right to think the future would resemble the past; and this is not of course just a one-off. Throughout our lives, we and scientists make predictions about how the future will turn out based on what we know about the past: that there will be a solar eclipse at such and such a time; that a certain drug is safe; that (as my experience quickly taught me) a 7 kg turkey needs to be cooked for more than two hours. So we might claim that we know as well as we know anything from experience that the future resembles the past.

Hume has an answer here too. "Our experience in the past can be a proof of nothing for the future but upon the supposition that there is a resemblance between them. This, therefore, can admit of no proof at all" (Hume 1740).

Our argument says that because, as it were, past futures have resembled past pasts, we have good reason to assume that future futures will also resemble the past. To make that a good inference we have to assume that the past (in which past futures have resembled past pasts) will resemble the future. But that is the very thing we wanted to prove. Trying to justify the claim that the past resembles the future by appealing to our experience is to argue in a circle.

This is very worrying. It suggests that all of our science rests on an unjustified assumption. Again we can see why a problem like this might be called first philosophy. The problem of induction calls into question all scientific results. No science can provide an answer to the problem because all sciences rely on induction and any such answer would be circular. Only philosophy could provide an answer, if an answer can be given at all.

Hume’s solution

Hume claims that it is impossible to justify our belief that the future will resemble the past, but we can explain where we get the belief from.

The experimental reasoning itself [what we are calling induction], which we possess in common with the beasts, and on which the whole conduct of life depends, is nothing but a species of instinct or mechanical power, that acts in us unknown to ourselves... [I]t is an instinct which teaches man to avoid the fire; as much as that, which teaches the bird, with such exactness, the art of incubation, and the whole economy and order of its nursery.

(Hume 1748: 108)

So we have an inborn instinct to reason inductively, according to Hume. It is just what we do and as a matter of fact it seems to work pretty well for us - but we have no justification for it. As we shall see, Hume's answer to the problem of induction has much in common with later naturalists' attitudes towards sceptical problems.

Kant and transcendental philosophy

So far we have looked just at first philosophical problems. Now, I want to look at what a first philosophical solution to these problems might be. By far the most important, influential, interesting and, unfortunately, complicated approach is Immanuel Kant's transcendental idealism. I shall not try here to give anything like a full account of Kant's philosophy. I shall sketch the general position quickly first and point out a couple of obvious problems, problems that are of particular interest to naturalists suspicious of first philosophy.

To begin our discussion of Kant we start with two other big figures from modern philosophy, Locke and Berkeley. Locke is, according to Kant, a transcendental realist. Like Descartes, Locke thinks that we know our own ideas directly. Some aspects of our ideas, such as shape and texture, match up to how things really are in the external world. These Locke calls primary qualities. Some aspects, such as colour and smell, do not. They are just caused in us by the powers of objects. These Locke calls secondary qualities. The problem for Locke is identical to the one Descartes encountered: how, given that we only know our ideas directly, can we be sure that they really match up with the world outside in the way Locke claims?

Berkeley has a very simple and utterly weird-sounding solution to Descartes's and Locke's problem. Deny the existence of the external world completely When we talk about objects that we normally take to exist in the external world, for example apples, what we are really referring to is a certain cluster of ideas that go together. In the case of apples, a certain sort of round shape, green colour, and appley taste and smell. There can be no sceptical worries about how we know about apples since all there is to apple is this cluster of ideas that we know directly. Kant calls Berkeley's view empirical idealism.

Kant's own view rearranges the labels he uses to describe Berkeley and Locke. Kant claims to be both a transcendental idealist and an empirical realist.

It is easiest to explain Kant's transcendental idealism and empirical realism by thinking about a particular dispute in metaphysics, the nature of space. We need again to introduce the ideas of two great thinkers that preceded Kant - Isaac Newton and Gottfried von Leibniz. Newton thought that space was a real thing, something like a giant box. All objects have a definite position in this real space; and even if there were no objects, space would still exist. Leibniz thought otherwise. Space is, he claimed, ideal. It is something we construct out of the relations between objects. So if there were no objects and no us to do the constructing, then there would be no space.

Kant's own view is a synthesis of these two seemingly contradictory ideas. The idea of space is a precondition for the possibility of the perception of any object. When we think of objects at all, we must think of them as in some space (and time). But we do not get the idea of space from experience. We supply the idea of space without which experience would be impossible. How is this a synthesis of Newton's and Leibniz's views? Looked at one way Newton is right to say that space is perfectly real and objective. Given the framework of spatial and temporal representations that we must bring to any perception, there are perfectly objective facts about when and where objects are located. This is the standpoint Kant calls empirical realism. Crudely, from the empirical realist standpoint the world is largely as we find it to be. This is the perspective of common sense and science. Looked at another way, though, Kant's views are much closer to those of Leibniz. Space abstracted from our perception of things is nothing at all. It is a precondition of any experience. "Space and ... time and with them all appearances are nothing but representations and cannot exist outside our mind" (Kant A490-1/B518-8). This is the perspective that Kant calls transcendental idealism. It is the special perspective of the philosopher; and the special task of the philosopher is to work out what the "conditions of possible experience" are - in other words, to work out what must be the case in order for us to have any perceptions at all.

Kant's account of space illustrates what he called his "Copernican revolution" in philosophy. "Hitherto it has been assumed that all our knowledge must conform to objects" but Kant thinks that we must "make trial whether we may not have more success in the tasks of metaphysics, if we suppose that objects must conform to our knowledge" (Bxvi). It is a way of understanding how we represent the world (and ourselves) that rejects the Cartesian picture illustrated above. Descartes as...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 First philosophy

- 2 Quine and naturalized epistemology

- 3 Reliabilism

- 4 Naturalized philosophy of science

- 5 Naturalizing metaphysics

- 6 Naturalism without physicalism?

- 7 Meaning and truth

- Conclusion

- Questions for discussion and revision

- Guide to further reading

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Naturalism by Jack Ritchie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.