eBook - ePub

Nation Building, State Building, and Economic Development

Case Studies and Comparisons

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Nation Building, State Building, and Economic Development

Case Studies and Comparisons

About this book

Why do some countries remain poor and dysfunctional while others thrive and become affluent? The expert contributors to this volume seek to identify reasons why prosperity has increased rapidly in some countries but not others by constructing and comparing cases. The case studies focus on the processes of nation building, state building, and economic development in comparably situated countries over the past hundred years. Part I considers the colonial legacy of India, Algeria, the Philippines, and Manchuria. In Part II, the analysis shifts to the anticolonial development strategies of Soviet Russia, Ataturk's Turkey, Mao's China, and Nasser's Egypt. Part III is devoted to paired cases, in which ostensibly similar environments yielded very different outcomes: Haiti and the Dominican Republic; Jordan and Israel; the Republic of the Congo and neighboring Gabon; North Korea and South Korea; and, Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. All the studies examine the combined constraints and opportunities facing policy makers, their policy objectives, and the effectiveness of their strategies. The concluding chapter distills what these cases can tell us about successful development - with findings that do not validate the conventional wisdom.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Nation Building, State Building, and Economic Development by Sarah C.M. Paine in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Imperial State Building:

La Mission Civilisatrice

La Mission Civilisatrice

1

Nation Building in India Under British Rule

DIETMAR ROTHERMUND

Abstract: This case study analyzes the unintentional aspects of British rule that turned out to contribute to nation and state building in India. It discusses the bureaucratic “steel frame” holding India together, the imposition of a legal system amalgamating British and Hindu legal traditions, the introduction of a new universe of discourse with the spread of British education, and the alternating current of national agitation and British constitutional reforms. At independence, the Indian personnel of Britain’s Indian Civil Service became the nucleus of the Indian Administrative Service, which provided administrative continuity during the change of governments. The independence movement contributed to nation building, as Indian nationalists tried to create a shared identity capable of unifying India after the British departure. Finally, the chapter deals with the traumatic experience of territoriality caused by the partition of India and the emergence of an independent democratic republic under the leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru, a passionate parliamentarian.

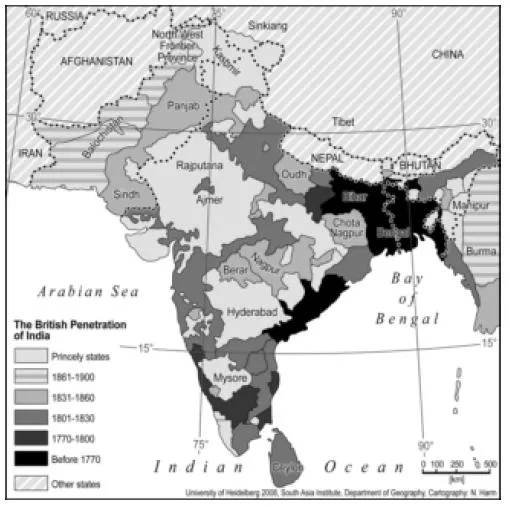

The British Challenge and the Indian Response

The British did not conquer India in order to build an Indian nation. On the contrary, most of the British posted in India never conceived of India as a nation and referred to it as “congeries of nations” which could never be united. They also used the old imperial strategy of divide and rule. And yet, they contributed unwittingly to nation building by their very presence. They imposed a more or less uniform institutional framework of governance on India so as to control it. But even more important was the challenge they provided to the Indians by demonstrating what a nation could do whose power was derived from social cohesion and efficient organization. In the eighteenth century, when the East India Company gained territorial control of large parts of India, there were about 6 million British people. The former Mughal empire had approximately 150 million inhabitants. It was a confrontation like that between David and Goliath. The match was even more uneven, because the number of British men sent to India was very small. The British did not invade; they hired Indian soldiers to conquer India for them and paid them with the money of Indian taxpayers. The Great Mughals had based their central power on a monetized land revenue. When the British gained control of the rich province of Bengal, they could use its revenue for financing their further operations in India.

British military strength was not based on superior weapons. All weapons used in those times were easily available to Indian rulers too. But the British introduced modern methods of infantry warfare, which consisted of making soldiers fire well-timed volleys at the enemy’s cavalry with a devastating effect.1 Traditional Indian musketeers were skillful marksmen, but they were not used to concerted attacks. A few British drill sergeants sufficed to teach them the new methods of warfare. The British were also better military paymasters than their Indian adversaries. Indian military heroes were often inept as far as financial matters were concerned. They might win a battle and then be unable to pay their troops, who promptly deserted. Officers in the service of a company of traders calculated their military ventures more carefully.

British military leaders in India also had other important characteristics that distinguished them from their adversaries. As members of a bourgeois nation, they never succumbed to the feudal temptation to become independent warlords after a victorious campaign. Warren Hastings, the first governor-general and the founder of the British empire in India, even humbly submitted to his recall and his impeachment by the British Parliament.2 He was accused of conquering large parts of India “illegally.” Although the Parliament impeached him, it never considered restoring those territories to their Indian rulers.

Another source of British strength was naval power, which had been neglected by Indian rulers. The most powerful local rulers were land based and did not care for maritime affairs. The smaller rulers, who controlled individual seaports, benefited from customs duties and welcomed traders of all nations. They never thought of trying to control or oppress traders, since they knew that maritime trade could easily shift to other ports. The despotic regime of the monsoon shielded India against maritime invaders, as their supply lines would be cut each year. This made Indian rulers complacent as far as control of their maritime periphery was concerned.

Only the perceptive young ruler of Maharashtra, Madhav Rao, remarked, in 1767, that the British had encircled India with a ring of naval power.3 By that time it was too late, even if Indian rulers had stopped their internecine warfare and had turned their attention to naval defense. The British had the best ships of the world at their disposal. In the 1660s the East India Company had closed its own dockyard and had adopted the very modern method of leasing rather than owning ships. Private ship owners then competed with each other to offer state-of-the-art ships to the company.4 These ships sailed very fast and were heavily armed. They were the pride of the British nation, and their captains were expert navigators who earned high salaries. National efficiency was clearly demonstrated by the performance of this impressive mercantile fleet. High freight charges imposed a strict discipline on its operations. Timetables had to be closely watched, as each day lost at sea meant a loss of much money. Capitalism subjected the British even at this early stage to its rigorous rules.

The Indians noticed the challenge posed by the British nation very slowly. Therefore their response took a long time. They were not confronted with a large foreign occupation army, which might have provoked immediate resistance. The British gradually usurped and transformed Indian institutions. After the decline of the Mughal empire, the commercialization of power had increased in India.5 Some Indian rulers mortgaged their states to merchants who organized the collection of their revenues and managed their treasury. In this context the activities of the East India Company were not unusual. This company could adjust much more easily to Indian conditions than an administration manned by royal officers of a foreign power would have done. The servants of the East India Company could play many roles. Initially they were hired as commercial employees only. Their salaries were meager, and they had to pay a large deposit when beginning their career. It was taken for granted that they would enrich themselves in India. The deposit would be forfeited only if they hurt the company’s interest by their machinations. If they served the company well, they could quickly rise to high positions.

The career of Robert Clive provides striking evidence of this flexible pattern of company rule.6 He went to India as a teenager and was first employed as a “writer,” or clerk, in the company’s office in Madras. In 1751 he emerged as a military hero in a war waged by the company against Indian rulers. He valiantly defended the fortress of Arcot against an Indian army. He then returned to his commercial line and made a fortune. He retired at an early age and campaigned for a seat in the British Parliament. He lost much money in the election campaign and did not win a seat. So he returned to India, after having procured the patent of a lieutenant colonel. He was sent from Madras to Calcutta, commanding troops of the East India Company. The Nawab of Bengal had taken action against the British settlement there because it had been fortified by the British, who had defied his orders. Clive defeated the Nawab in 1757 and established British rule over this fertile province, becoming its first British governor. The Battle of Plassey, which Clive won, was a mere skirmish. His success was due to bribery rather than to military valor as the Nawab’s general deserted to join forces with Clive. (The traitor’s name, Mir Jafar, is still a synonym for treachery in India.) There was no parallel to Mir Jafar’s behavior among the British. Clive was cunning and devious, and he lined his pockets with Indian money, but he faithfully served the British cause.

When the East India Company became a territorial ruler, the methods of Clive and his contemporaries had to be changed. The commercial servants of the company became “civil servants” who earned high salaries, which were supposed to prevent them from succumbing to corruption. The company established a special college at Haileybury, in England, where the candidates for the civil service were trained. They followed regular careers, starting as a district officer and ending as a secretary to government or even as a member of the governor’s council. They were freely transferable and were expected to cope with any assigned task. Indians had earlier been ruled by military commanders, who employed scribes to do the administrative work for them. Now they were to be ruled by British scribes.

Administration: The Bureaucratic “Steel Frame”

The comparison of the British civil service in India with a “steel frame” that kept the country together was made by Prime Minister Lloyd George in 1922. It was not an expression of imperial bravado, but rather a desperate plea at a time when the star of the empire was sinking. Lloyd George wanted to attract to this service young British men who were no longer certain whether they could look forward to a lifetime career in India. After India had gained independence in 1947, the powerful home minister, Vallabhbhai Patel, used similar words in order to defend the maintenance of the “steel frame,” now manned by Indians. Addressing the Constituent Assembly, he asserted that the country had to be kept together by a “ring of service.”7 His arguments were accepted. There was a change in name only: the old Indian Civil Service (ICS) became the new Indian Administrative Service (IAS). The rules of the service remained the same; it was centrally recruited and was under the jurisdiction of the central home ministry. The terms of service were enshrined in a special section of the Indian constitution.8 The officers of this service could be freely transferred. They usually started their career in a district, and would then rise to higher positions in the respective state government or could be deputed to a central ministry. They could also be put in charge of a large public sector enterprise. As “generalists” they were supposed to be able to cope with any task assigned.

Vallabhbhai Patel was a staunch nationalist and a close associate of Mahatma Gandhi. He could be expected to hate the civil service, whose members had jailed so many nationalists in the course of the freedom movement. In fact, the members of the service feared that Patel might take revenge, disband the service, and even prosecute individual members for what they had done under British rule. Instead Patel surprised them by wholeheartedly opting for the “ring of service”—and they did keep the country together. This was a striking instance of adopting a British legacy and using it in the interest of state building. Patel’s decision was prudent. The Indian national leadership had not attained power in a violent revolution but in a “transfer of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Maps and Table

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I. Imperial State Building: La Mission Civilisatrice

- Part II. The Anticolonial Reaction: The Rejuvenation of Old Polities

- Part III. Creating New States: Divergent Pairs

- About the Contributors

- Index