Introduction

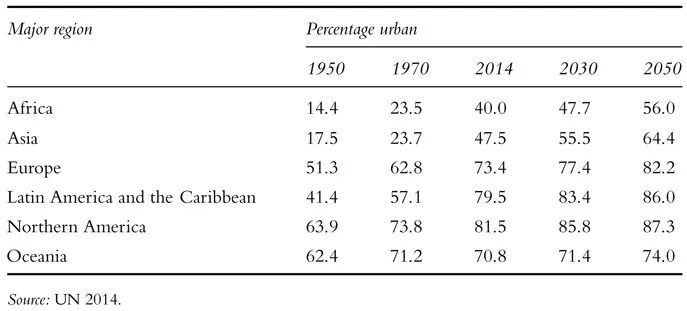

An important milestone occurred in mid-2009, when the world’s population, at that time about 6.8 billion, became more urban than rural. By 2050, when the world population is expected to have increased to 9.5 billion, approximately 66% of the world’s population will be living in urban areas (UN 2014). Levels of urbanization differ when one looks at different continents. As Cohen (2006: 70) states: “There are enormous differences in patterns of urbanization between regions and even greater variation in the level and speed with which individual countries or indeed individual cities within regions are growing”. Currently, Asia and Africa still have a predominantly rural population, while Europe, North America and Oceania were already urbanized regions before 1950. By 2050, however, all major areas will be urbanized (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Urbanization trends by major regions (1950–2050)

Urbanization is and will partially be taking place through the growth of mega cities, cities with a population of more than 10 million (Sorensen and Okata 2010). However, the vast majority of urban population growth will occur in smaller cities and towns (i.e., urban settlements with a population of less than 1 million residents), followed by medium-sized cities (1–5 million residents). According to Cohen (2006), about 10% of the world’s urban population will be living in mega cities, while just over half of the total urban population will reside in the smaller cities and towns.

Both mega cities and smaller cities face several development, governance and sustainability challenges, albeit that in some cases the kind of challenges differ substantially between the two. According to Sorensen and Okata (2010: 7–8), the increasing speed of urbanization has major consequences for mega cities: “building infrastructure takes time as well as money, and rapid growth often means that there is not enough of either to keep up with needs. Perhaps more fundamentally, political processes and governance institutions take time to evolve and generate effective frameworks to manage complex systems that make giant cities more liveable”. The governance capacity is also mentioned as a challenge for the smaller cities and towns: “many small cities lack the necessary institutional capacity to be able to manage their rapidly growing populations” (Cohen 2006: 74). The increasing governance complexity is not only due to the rapid urban population growth, but is also a result of the decentralization of regulatory responsibilities and policy implementation: “In the areas of health, education, and poverty alleviation, many national governments have begun to allow hitherto untested local governments to operate the levers of policy and programs” (ibid.: 74–75).

In addition to shifting governance responsibilities and growing governance complexities for cities, urbanization also poses a number of other challenges. One of these challenges is resource use (Madlener and Sunak 2011). Cities consume 75% of the world’s resources, while covering only 2% of the world’s surface (Pacione 2009), which means that the vast majority of resources used by a city are taken from, and produced in, places outside cities’ borders. This is often referred to as the urban ecological footprint: “the total area of productive land and water required continuously to produce all the resources consumed and to assimilate all the wastes produced, by a defined population, wherever on Earth that land is located” (Rees and Wackernagel 1996: 228–229). Hence, the ecological footprint is “a land-based surrogate measure of the population’s demands on natural capital” (ibid.: 229). In the process of urbanization, the urban ecological footprint, expressed in the annual demand for land and water per capita, has increased, particularly due to the growing energy demand for mobility, for cooling and heating of houses and offices, for all sorts of equipment for domestic use, and for long-distance transport, processing, packaging, cooling and storage of food (Lang 2010, Madlener and Sunak 2011). The growing ecological footprint of cities has also resulted in a characterization of cities as “parasites”, exploiting the resources of its rural hinterland while simultaneously polluting land, water and air (Broto et al. 2012). A shortcoming of the urban ecological footprint approach is that it is based on the average annual resource use per capita, thereby obscuring differences between urban dwellers within cities.

This brings us to another urbanization challenge: growing inequalities in wealth, health, access to resources and availability and affordability of services (Cohen 2006, Broto et al. 2012). Historically, cities developed in places that had a natural advantage in resource supply or transport and that hence offered opportunities for social and economic development: “cities have always been focal points for economic growth, innovation and employment” (Cohen 2006: 64). In most major regions of the world urbanization has gone hand in hand with economic development. This does not hold true for Africa, where current urbanization seems to occur despite economic development: “cities in Africa are not serving as engines of growth and structural transformation” (World Bank 2000 cited in Cohen 2006). Rather, these cities serve as a magnet for those seeking a better quality of life. However, the structural investments to provide this are largely lacking or at least insufficient. Urban growth generally means that cities become culturally and socioeconomically more diverse. Typical for many cities in developing countries, regardless of whether these cities are small, medium-sized or very large, is the significant difference between the upper- and middle-class and the low-income class with regard to access to clean drinking water and electricity and presence of adequate sewerage and solid waste disposal facilities (Cohen 2006, Broto et al. 2012). The reproduction, or perhaps even acceleration, of urban inequalities is often attributed to poor urban governance – i.e., municipal authorities unable to keep up with the speed of urban growth and/or with the increasing complexity of urban governance as a result of decentralization of policies – and neo-liberal reforms of urban services, which tend to exclude the urban poor from access to these services (Broto et al. 2012).

A fourth challenge of urbanization often mentioned in the domain of urban studies is environmental pollution, like water pollution across the developing world and air pollution, in particular when it comes to mega cities (Mage et al. 1996, Cohen et al. 2005). The images of cities full of smog and pedestrians wearing face masks to protect themselves from air pollution are telling examples of the problem of urban air pollution. Traffic congestion is considered to be a major source of air pollution in developing countries: “Over 90% of air pollution in cities in these countries is attributed to vehicle emissions brought about by high number of older vehicles coupled with poor vehicle maintenance, inadequate infrastructure and low fuel quality” (www.unep.org/urban_environment/issues/urban_air.asp). The greatest environmental health concerns caused by air pollution are exposure to fine matter particles and lead. This contributes to learning disability in young children, increase in premature deaths and an overall decrease in quality of life (Cohen et al. 2005, Cohen 2006). As “vegetation can be an important component of pollution control strategies in dense urban areas” (Pugh et al. 2012: 7693), the prevalence of air pollution in cities worsens due to the disappearance of the urban green (Pataki et al. 2011). The lack of urban green also contributes to urban heat islands, an urban environmental health challenge that is aggravated by climate change (Susca et al. 2011). Heat islands “intensify the energy problem of cities, deteriorate comfort conditions, put in danger the vulnerable population and amplify the pollution problems” (Santamouris 2014: 682). Recent research indicates that green roofs can play an important role in mitigating urban heat islands and hence in reducing the urban environmental health problems resulting from climate change (Susca et al. 2011, Santamouris 2014).

An urban challenge that is gaining attention, but which was ignored for a long time in urban studies as well as in urban policies and planning, is food provisioning. Neglecting the dynamics and sustainability of food provisioning in scientific research on sustainable urban development is a serious omission, because, as Steel (2008) argues, “feeding cities arguably has a greater social and physical impact on us and our planet than anything else we do”. Like Steel in her much acclaimed book Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives, the founders of food planning in the USA, Pothukuchi and Kaufman (1999: 216) state that in urban policy “food issues are hardly given a second thought” because urban policies are usually associated with issues such as “the loss of manufacturing jobs, rising crime rates, downtown revitalization, maintaining the viability of ageing neighbourhoods, and coping with rising city government expenditures”. This is also reflected in the names of municipal departments and the domains for which municipalities usually bear political responsibility (although this may differ between countries): planning and spatial development, finances, waste management, health, public transport, education, parks and recreation, and community development.

One reason why food has never been a prominent issue on the urban agenda is rooted in the persistent dichotomy between urban and rural policy. Food is often seen as part of the realm of agriculture and hence as belonging to rural policy. According to Sonnino (2009), this urban–rural policy divide is responsible for three shortcomings in urban food research, policy and planning:

- a) The study of food provisioning is confined to rural and regional development, missing the fact that the city is the space, place and scale where demand is greatest for food products.

- b) Urban food security failure is seen as a production failure instead of a distribution, access and affordability failure, constraining interventions in the realm of urban food security.

- c) It has promoted the view of food policy as a non-urban strategy, delaying research on the role of cities as food system innovators.

Linked to the urban–rural policy dichotomy is ignorance among many urban dwellers and policy officials about the significance of food for sustainable urban development and quality of urban life (Pothukuchi and Kaufman 1999), although this is more likely to be the case in cities where the availability of food has never been a real issue of concern for the “average” urban dweller. According to Pothukuchi and Kaufman (1999: 217), food should be understood as an important urban issue as it is “affecting the local economy, the environment, public health, and quality of neighbourhoods”.

In this chapter, I want to elaborate on this by presenting and discussing the conditions that are shaping urban food systems. An urban food system encompasses the different modes of urban food provisioning, in other words, the different ways in which locations where food eaten in cities is produced, processed, distributed and sold. This may range from green leafy vegetables produced on urban farms, to rice produced in the countryside surrounding the city, up to breakfast cereals produced, industrially processed and packaged thousands of kilometres away from the place of consumption. The food provisioning system of any city, whether small or large, in Europe, sub-Saharan Africa or Latin America, is always a hybrid food system, i.e., combining different modes of food provisioning. Some cities are mainly, though not exclusively, fed by intra-urban, peri-urban and nearby rural farms and food processors, while other cities are largely dependent, though not entirely, on food produced and processed in other countries or continents. Hence an urban food system is not only shaped by the dynamics characteristic for that particular city-region (i.e., the city and its urban fringe and rural hinterland), but also, and sometimes even predominantly, by dynamics at a distance. This is why the elaboration of the conditions shaping urban food systems is somewhat of a global and generic nature, introducing and explaining the main trends influencing urban food system dynamics. I will introduce some examples to highlight more concretely how and to what extent a city’s food system is influenced by these conditions. However, the primary aim of this chapter is to introduce the different topics and themes related to urban food systems, and more in particular to (intra- and peri-) urban agriculture, elaborated upon in the following chapters in the book.

Building on these conditions, I want to conclude this chapter by proposing and discussing several guiding principles for designing and planning future urban food systems. Also this will touch upon issues that are further developed, discussed and illustrated in the following chapters.