Learning objectives:

After reading this chapter, readers will be able to:

• Identify and analyze the importance of strategic planning process and strategic management to have a successful organization.

• Define what is meant by the concept “strategy.”

• Differentiate between goals and objectives.

• Apply and explain the different components of the dynamic strategic management process.

• Analyze the role of stakeholders and their impact on the strategic success of an organization.

• Identify the key responsibilities of organizational strategists in strategy formulation of an organization.

• Understand the cultural influences on the strategic planning process in light of rapid globalization.

• Recognize the importance of environmental scanning in strategy formulation and implementation.

The quotation from Tom Peters illustrates a strategic management approach to what may be a generally held fallacy on the part of many students taking a course in strategic management. There is a tendency to look at a successful organization and conclude that since everything seems to be working well, no changes are necessary; i.e., “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it!” All options cannot be chosen simultaneously, but sound reasons should underlie why they are not being chosen. The study of strategic management/planning is largely about that kind of investigation.

Further, it is about choosing courses of action in an integrated fashion, and continually ensuring that the course of action selected continues to be the most appropriate one. Continuous improvement is essential in a highly flexible corporate world.1 In other words, doing what you are (or have been) doing may really be the best option, but you can only be sure of that as a result of continuous investigation.

Importance of strategic management and planning

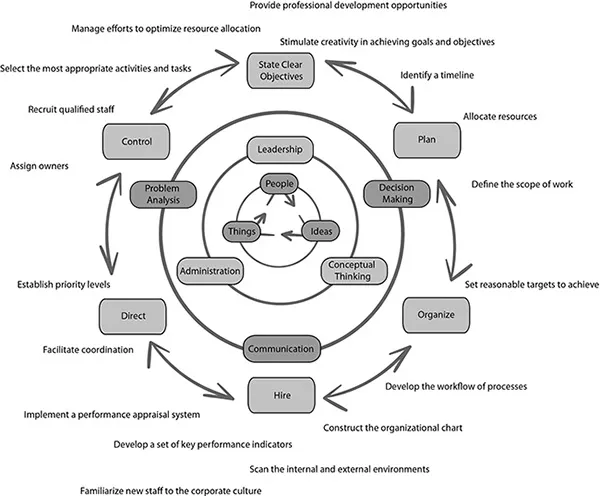

Before even attempting to offer a definition of what strategic planning is, it is important to state that when some organizations want to change, they plan for it, and this planned change is part of the overall management approach. Traditionally, management activities have been planning, organizing, recruiting, selecting, leading, communicating, relating, problem solving, decision making, negotiating, conflict using, training, controlling, rewarding, evaluating, and innovating. But management is more than this, and it is subject to continuous change. R. Alec Mackenzie takes a three-dimensional view of the management process as it is presented in Exhibit 1.1. This model focuses on the basic elements of management activities: people, who create the need for leadership to influence people to achieve desired objectives; things, which create the need for administration; and ideas, which create the need for conceptual thinking. Three functions permeate the work process: problem analysis, decision making, and communication. Then, we see that the other aspects of management flow from these components. Successful management is the integration of all the parts without neglecting the rest of the functions. Mackenzie envisions a sequential connection among many of these elements: the objectives of an undertaking have been clearly stated, then planning and organizing follow, which lead to the need for staffing, directing, and controlling in terms of the dynamic plan. The cyclical approach to management provides a unified concept for fitting together the management activities, as well as for distinguishing leadership, administrative, and strategic planning functions. Through this dynamic process, it is likely that circles of activities could be added within this basic paradigm as changes require them.

Another point that needs to be made here is that each element in the management process is culturally conditioned. Thus, managerial activities or interpretations of basic functions may differ from culture to culture. This is why business schools offer courses in international business, comparative management, etc., and why several companies offer training sessions that address cultural sensitivity issues and cross-cultural management approaches.

Keeping in mind the current business environment, companies have to assess the gap between their current organizational capacity (in particular, executive management) and long-term plans. Unlike before, they cannot leave their leadership development to chance or to be restricted to cultural and linguistic complexities with regard to their expansion plans. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) has recognized the important impacts of the national leadership development along with cultural intelligence initiatives on both human capacity building as well as the national economy by adopting the nationalization initiative.2 Similarly, countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations are capable of increasing their shares from the global trade; nevertheless, they would face a scarcity of available leadership talent in the region. Such companies would face huge challenge finding leaders who are capable of managing effectively the human resources, adjusting to the culturally affected managerial processes, and creating values to their companies in light of the multitude of cultures with more than 600 million people speaking different languages and dialects.3

Like most people, you have probably worked somewhere during your life as a student, or as a practitioner even if only part time. You might have held jobs in retail sales, fast-food chains, restaurants, or in the construction industry. In those jobs, or any others that you might have experienced, did you feel as if the organization had some sort of a strategic plan for success? If so, did you understand how your specific job was integrated into the organization’s grand scheme? Although it may not have been immediately obvious, such things as your job training and subsequent performance analyses should have represented the organization’s strategic direction, although unfortunately, that is not always the case.4

For example, if you worked as a waitperson in a restaurant, was your objective to get the customers in and out quickly, or was it to encourage a long eating cycle with appetizers and before- and after-dinner drinks? Was your restaurant one that provided a relatively limited menu of certain kinds of foods, or was it a buffet, intended to satisfy a wide range of customer tastes? Each of these approaches implies a specific strategy followed by that organization. In considering these simple questions, you can begin to understand the importance of strategic planning. The organization has defined itself in terms of what it wants to be and how it will compete within its industry. As that industry becomes increasingly complex, you can begin to appreciate just how challenging this concept can be to even the most experienced managers.

Ask yourself another question. Are the organizations you worked for still viable, ongoing businesses? If so, do they still operate in essentially the same way they did when you worked there? If not, you can begin to see just how much change has become a part of our everyday organizational lives. This decade has been characterized as one of “chaos” and “turbulence” for corporations.5 Furthermore, such terms as reengineering, mergers, acquisitions, downsizing, rightsizing, revitalization, total quality management, and paradigm shifts have become commonplace. Strategic management and planning provides a framework for seeking profitable ways for the organization to adapt to change, and in many cases, anticipate the change and make it work for them.

Even in the relatively rare cases in which significant change is not experienced, strategic management and planning helps to give the organization a framework in which to operate most efficiently and effectively in their environment. Although more terms will be defined more precisely later in this chapter, for now the definition of strategic planning is the process by which a system maintains its competitiveness within its work environment by determining where the organization is, where it wants to go, and how it wishes to get there.6 In other words, examining ...