![]()

1

Re-Awakening the Power of Place

Ancient philosophy and practice with relevance for protected areas and conservation in Asia

Bas Verschuuren

General introduction

This book sheds light on how ancient philosophies and practices related to sacred natural sites are relevant to conventional protected areas and conservation in Asia today. In doing so it contributes to the field of conservation practice and interdisciplinary research on sacred natural sites that draws from the social and natural sciences. This field is gaining in popularity as testified by an increased number of peer reviewed and professional publications and the uptake of the topic in course curricula and conservation initiatives (see preface).

This book offers a unique regional perspective on sacred natural sites and features contributions from local custodians, religious studies scholars, conservationists, researchers and academics. It is currently being complemented by two other volumes taking regional approaches to the topic. Sarmiento and Hitchner (2016) focus on the Americas while Heinamäki and Herrmann (2016) focus on the Arctic regions. The book includes case studies, national perspectives and global outlooks. It is divided into sections that offer different thematic perspectives on how sacred natural sites have the power to reconcile the traditional and the spiritual with conventional conservation objectives; these are:

- Themes and perspectives on the conservation of Asian sacred natural sites.

- National outlooks and strategies for the conservation of sacred natural sites.

- Legal approaches and governance of sacred natural sites.

- Conservation of sacred lands meeting challenges of development.

- A role for custodians and religious leaders in the conservation of sacred natural sites.

- Dualing spirits and sciences: revisiting the foundations of conservation.

Each section is preceded by a brief introduction and made up of three to four chapters. Sections are not strict separations of themes and most chapters also hold relevance to themes addressed in other sections. A cross-cutting discussion that underpins the book sections is about the ontological and epistemological synergies and disconnects between conservation approaches and practices of sacred natural sites custodians.

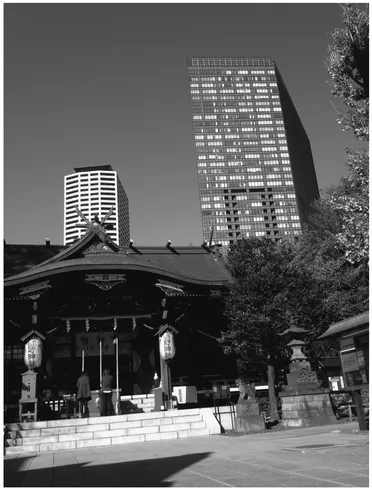

FIGURE 1.1 A Shinto shrine in the heart of Tokyo. With soaring prices for land this shrine is surrounded by a lush temple forest that offers not only spiritual amenities but also relaxation to its visitors. Source: Bas Verschuuren.

This introduction starts with an overview of the study of sacred natural sites in the domain of nature conservation and continues by relating the topic of sacred natural sites to Asian philosophy and religion. It then presents examples of sacred natural sites in Asia and provides a map of the sacred natural sites discussed in this book (see Figure 1.2). Religious and spiritual values form the basis of many of the practices and behaviours of people and this is understood in the field of spiritual ecology (Sponsel 2012). However, contemporary protected areas and conservation approaches are largely uninformed by ancient and traditional cultural practices and philosophies and often do not take those into account. In order to better understand this a brief overview of the old philosophy of protected areas including its colonial and scientific heritage is presented. These stand in stark contrast with ancient cultural approaches to conservation such as sacred natural sites and indigenous and community conserved territories. This overview is followed by a summary of recent developments in conservation, focusing on the inclusion of people particularly in protected areas and the recognition of other area-based conservation measures, or OECMs (explained further on in this chapter). These developments signal a new paradigm for conservation and protected areas that is more inclusive and appreciative of the spiritual, religious and philosophical dimensions of sacred natural sites. Finally, it is discussed how sacred natural sites contribute to this new paradigm by reawakening the power of place and uniting ancient philosophies of protected areas with conventional ones.

A history of sacred natural sites in conservation

Sacred natural sites is a term that was coined by conservationists, see Lee and Schaaf (2003: p. 13) who put sacred and cultural sites forward for their contribution to nature and biodiversity conservation, as they were structurally being overlooked by conservationists. Sacred Natural Sites have deliberately been broadly defined as ‘areas of land and or water that have special spiritual significance to people’ (Wild and McLeod 2008; see Verschuuren et al. 2016 for a more elaborate exploration). Mostly, sacred natural sites are, as the name suggests, natural features such as groves, mountains, lakes, springs, meadows, rocks, etc. although entire landscapes or ecosystems are also known to be classified as sacred. Sacred natural sites are numinous, they possess agency and in their oldest form are often animated and imbued by spirits. Sacred natural sites can be marked by man-made constructions such as shrines, mosques, churches and temples. The latter are typical of the sacred natural sites of mainstream faiths that are often succeeding the sacred natural sites of their ancient animistic predecessors. A significant difference between the two is that most sacred natural sites of mainstream faiths are no longer rooted in an animated spirituality that is innate to nature. Mostly these are dedicated to the worship of saints, angels or other transcendent beings associated with that particular faith and residing in the sacred natural site or acting as a protector deity.

The preface to this book provides a brief account of the role of sacred natural sites in the field of conservation, but several authors offer concise overviews: Tiedje (2007) and Verschuuren et al. (2010; 2016). Robson (2011) and Byrne’s Asian perspectives (2010, 2012) advance these by delivering critical analyses and highlight yet understudied, unrevealed and previously hidden or omitted conceptualisations and framings of sacred natural sites in this conservation narrative. So far, most academic work on sacred natural sites has a conservation focus while other aspects largely remain under researched. The first peer reviewed book on the subject by Verschuuren et al. (2010) includes also seven chapters on sacred natural sites in Asia and broadens the scope to the conservation of both cultural and natural diversity. This biocultural approach to conservation is continued by Pungetti et al. (2012) who also add a focus on sacred species.

Although Asian Sacred Natural Sites: Philosophy and practice in protected areas and conservation retains a ‘technical conservationist style of writing’, throughout some of its chapters it recognises the need to embrace previously undervalued worldviews, the supernatural and the numinous that instil agency in sacred natural sites and make them capable of creating real change. It includes deeper ethnographic perspectives on religiosity and addresses some of the ontological disjunctures between the perspectives of custodians and conservationists (Samakov and Berkes, Ch. 17; Liljeblad, Ch. 11) as well as cultural and religious contestations central to ‘new’ narratives and approaches for the protection and conservation of sacred natural sites (Studley, Ch. 21; Borde, Ch. 9; Hou, Ch. 23). In search of these new narratives the next section explores some philosophies and religions in Asia so as to understand their intricate and ancient relations with the conservation of sacred natural sites.

Philosophy, religion and spirituality across Asia

The Asian continent bears the footprints of all of the world’s major religions: Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, Daoism, as well as the Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam (that generally stand apart as they denounce idolatry) (Berkes 2013). Many of these religions have ancient roots vested in their animistic predecessors such as Bon Shamanism in Southeast Asia, Bilik, Tengri and other strands of Shamanism in Central Asia’s Altai and Shinto in Japan. New shoots sprouting from them have resulted in coexistence or syncretism with these mainstream faiths and indigenous spiritualities have given rise to folk religions. This diversity of religions, syncretic and animistic belief systems have also influenced the development of indigenous knowledge systems or even complete cultural philosophies such as Ayurveda, Yoga and Fung Shui. Some of the major religions such as Daoism and Buddhism are at times classified as philosophies. Across Asia we find different philosophies such as Korean, Jain, Buddhist and Hindu while Japanese philosophy starts were Confucianism and Buddhism merged with its animistic predecessor Shinto. Asian Sacred Natural Sites: Philosophy and practice in protected areas and conservation testifies to the ways in which these philosophies, religions and their related practices contribute to protected areas and the conservation of nature and culture.

The philosophical study of the relationship between spirituality and nature is equally complex and has many expressions across these different Asian faiths and philosophies. Some of these inquiries are thousands of years old, such as in Hinduism while others are more recent such as Sikhism (founded around 1500 AC.). New thinking may drive religious and socio-cultural diversification, see Borde and Jackman (2010), Yuxin Hou (Ch. 23). Religion and philosophy related to sacred natural sites has shaped Asian culture, society and of course people’s thinking and their resulting practices related to protected areas and the conservation of nature throughout the continent.

All religious teachings on human relationships with nature contain a significant spiritual element. In Hinduism, the Bhagavad Gita for example, shows that life without contribution toward the preservation of nature is a life of sin and without specific purpose or use. The very embodiment of God and goddesses in natural features such as in sacred groves, mountains and rivers, think of the river Ganges (Singh and Rana, Ch. 6), further illustrate these age-old spiritual ties that serve the conservation of nature and natural elements that have been venerated since time immemorial. Zoroastrians in fact are known for their claim on being the world’s first organized religion that acts as a proponent of ecology, through caring for the elements and the earth (see Hassani Esfahani, Ch. 22). On the other hand the veneration of natural elements and sacred natural sites is not a panacea for protection and conservation – think of the holy river Ganges that is one of the most polluted rivers in India. Several chapters in this volume show that large numbers of religious pilgrims can have serious impacts on fragile ecosystems and require religious actors and conservationists to take radical responses (see for example Kaur and Balodi, Ch. 16, Bernbaum, Ch. 3, Singh and Rana, Ch. 6).

Over the past decades the cultural and religious motivations for governing and managing natural resources have become of increasing interest to those working in the fields of nature conservation and cultural heritage (Palmer 2005; Tucker 2012; Mcleod and Palmer 2015). These developments also draw on examples from across Asia. Not only do faith groups increasingly take on responsibility for caring for the environment (or creation), we also see a gr...