- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Human Evolution

About this book

For the one-term course in human evolution, paleoanthropology, or fossil hominins taught at the junior/senior level in departments of anthropology or biology.This new edition provides a comprehensive overview to the field of paleoanthropology–the study of human evolution by analyzing fossil remains. It includes the latest fossil finds, attempts to place humans into the context of geological and biological change on the planet, and presents current controversies in an even-handed manner.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Trends in Human Evolution

Overview

Trend 1: The Evolution of Bipedalism

Trend 2: Effective Exploitation of the Terrestrial Habitat

Trend 3: Increasing Brain Size and Complexity

Trend 4: Extensive Manipulation of Natural Objects and The Development of Motor Skills to Facilitate Toolmaking

Trend 5: The Increased Acquisition of Meat Protein

Summary

Suggested Readings

OVERVIEW

The human body is the complex culmination of millions of years of evolution. Our social organizations, advanced technology, and relationship with the living world are also outcomes of the evolutionary process. Despite the complexity, years of research have provided us with a glimpse into our distant past and have delineated the general trends and basic evolutionary principles that led to our place in nature today. These trends made us unique among the primates—an evolutionary group including prosimians, monkeys, apes, and humans—while alternative evolutionary pathways made every nonhuman primate unique as well.

Understanding evolutionary trends is key to knowing what to look for in the fossils that represent our long evolutionary journey. The overall picture helps paleoanthropologists to formulate and test hypotheses regarding the mode, causes, and tempo of evolution. Thus, in this opening chapter we will outline five key trends to form a basis of understanding human origins. The history of fossil discovery and analysis has set the stage for our understanding of these trends, so we open our text with the following brief overview of some cornerstone events that shaped our modern views.

Well over 2 million years ago, a young child met a premature demise while walking near a small stream, tottering on two legs. His body fell into the water, or was dropped there by a predator, and floated to the back of a nearby cave. Eventually, the body sank into the soft sediments below, beginning the process of fossilization. Over many millennia the child’s apelike skull became encased in rock as the sediments hardened. The skull resurfaced in 1924, when it was blasted out with dynamite during quarry operations near the village of Taung, South Africa (Figures 1-1 and 1-2).

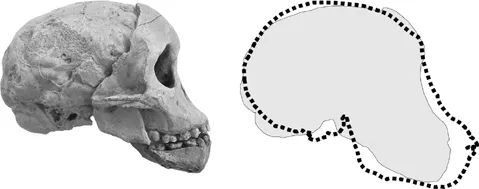

Through a set of fortuitous circumstances, the skull was taken to Raymond Dart, then an anatomy professor at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. In 1925, Dart announced the discovery of early “ape-man” remains and attributed them to a newly created genus, Australopithecus (Figure 1-3). A short description of his findings appeared on February 7, 1925, in the British journal Nature. Dart’s preliminary description was based on the facial skeleton and an associated endocranial cast—a natural mold of the inside of the cranium formed of solidified sediment. The skull was of a 3- or 4-year-old child, probably a male, who had become entombed in the ancient cave deposit and recovered at the site of Taung.

FIGURE 1-1 Africa’s role in human evolution first came to light with quarry activity at the Buxton Lime-works, Taung, South Africa, in 1927. The pinnacle on the right is close to the spot from which the Taung Australopithecus skull was blasted out by dynamite in 1924. The photo was taken by the late Italian anthropologist Lidio Cipriani. (Courtesy Jacopo Moggi-Cecchi.)

FIGURE 1-2 Remnant pinnacles of the limestone quarry at the Buxton Limeworks, Taung. The Taung Australopithecus skull came from a spot near the pinnacle in the foreground. (Courtesy Jeffrey K. McKee.)

It took Dart, using his wife’s knitting needles, seventy-three days to clear away enough of the adhering limestone matrix to reveal the face and part of the skull. It took him a full four years to extract the bone completely from the rock encasement. Dart later remarked that when he was first able to see the face, in late December, “What emerged was a baby’s face, an infant with a full set of milk (or deciduous) teeth and its first permanent molars just in the process of erupting. I doubt if there was any parent prouder of his offspring than I was of my ‘Taung baby’ on that Christmas of 1924” (Dart and Craig, 1959:9).

FIGURE 1-3 Left: The Taung skull, type specimen of Australopithecus africanus. Right: The silhouette of the Taung skull is compared with the outline of a juvenile chimpanzee skull of approximately the same developmental age (dashed line). (Courtesy Jeffrey K. McKee.)

Dart was convinced that the skeletal remains belonged to a “man-like ape” that stood erect and walked bipedally—on two legs. This deduction was based on the relatively forward position of the foramen magnum, the large hole at the base of the skull where the spinal cord meets the brain. This suggested that the spinal cord entered from below, as in humans, rather than from behind the skull, as in modern apes. He named the fossil Australopithecus africanus, the southern ape of Africa. Dart stated, “The specimen is important because it exhibits an extinct race of apes intermediate between living anthropoids and man” (1925:195).

Although Dart was convinced of both the importance of his find and its place in human evolution, most other scientists rejected his contentions. At the time of Dart’s writing, there were many competing theories of human evolution, all based on very fragmentary remains and not unduly restrained by the facts. The Taung fossil was rejected as a human ancestor because it did not fit into the theories then being championed by recognized scholars. Besides belonging to a juvenile, the fossil, in light of the current theories, was found in the wrong place, was dated too late in time, and possessed the wrong morphological characteristics.

In 1925, Asia, not Africa, was considered the place of human origins because of earlier Homo erectus finds. When material was recovered from Zhoukoudian, China (Chapter 10), it was cited as proof of the correctness of the Asia-as-homeland viewpoint. The material from Zhoukoudian, the so-called Peking man, was readily accepted into the human fold.

The Taung child was initially thought to date to the latter part of the Pleistocene epoch, which is now known to date from 1.8 million to 0.01 million years ago (mya). The late Pleistocene was considered by most to be too late in geological history for an early human ancestor. Said British anatomist Arthur Keith, one of Dart’s chief critics: “A genealogist would make an identical mistake were he to claim a modern Sussex peasant as the ancestor of William the Conqueror” (1925a:492). Most authorities accepted a human-ape branching during a much earlier geological epoch. This idea was based in part on a mistaken notion of the geological time scale. At the turn of the twentieth century, the age of Earth was considered to be only about 65 million years, and the total period of mammalian evolution was relegated to the last 3 million years of geological time. Humans were considered to have appeared early in mammalian evolution. Even when geological time was revised backward, some scientists continued to suggest that the Taung child appeared too late to be a human ancestor.

Another factor that led to Taung’s rejection was the notion that the brain preceded the rest of the body in evolving toward a human form. Taung did not fit this conception, for it had a small cranial capacity, which is closely related to the size of the brain. Furthermore, Taung had a more humanlike face and dentition than were expected. But the strongest argument against a position in human evolution came in the form of the Piltdown material. Piltdown was a site in England that had yielded a humanlike skull with an apelike face—material that had been cleverly doctored and planted in the site (Chapter 3). Until this material was finally shown to be a hoax in the early 1950s, many fossils were measured against Piltdown’s incongruous nature (that is, a human skull, large cranial capacity, and an ape’s jaw). The faked Piltdown material fit preconceived notions of human evolution; Taung did not. (Arthur Keith, Dart’s most vigorous critic, has been implicated as a possible perpetrator of the fraud.)

While Dart’s interpretations concerning early human evolution in Africa were being rejected, Robert Broom entered the fray. Broom, a famed South African paleontologist, soon became convinced that Dart was correct. From the cave site of Sterkfontein, South Africa, Broom later recovered a remarkable series of Australopithecus fossils, including adult crania and limb bones. These finds verified Dart’s contention that Taung represented an upright, bipedal animal, and was a valid contender as a possible human ancestor. Despite Broom’s additional proof of Dart’s interpretations, others remained unconvinced that the South Africa fossils represented an early member of the human lineage.

Dart had another supporter in the famed neuroanatomist Grafton Elliot Smith, an old friend and mentor. Elliot Smith (1925) noted that the scientific community should not be surprised by Dart’s discovery, not if they “know their Charles Darwin.” He was referring to something Darwin had written in The Descent of Man in 1871:

It is therefore probable that Africa was formerly inhabited by extinct apes closely allied to the gorilla and chimpanzee; and as these two species are now man’s nearest allies, it is somewhat more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere. (p. 199)

Dart’s discovery proved Darwin’s prescient insight that human origins probably began in Africa. Today there are hundreds of early prehuman fossils vindicating Dart’s analysis of Taung. Clearly, human origins began with small-brained, bipedal animals living in Africa, possibly as much as 6 mya. A number of species of Australopithecus, collectively known as the australopithecines, have been found in South Africa, East Africa, and Chad. Tantalizing fossils of their potential ancestors are now emerging from the same regions. Fossil remains of our own genus, Homo, demonstrate the evolution and spread of near-human forebears.

As our vision of the road to Homo sapiens has become clearer, five general trends have garnered strong scientific support.

TREND 1: THE EVOLUTION OF BIPEDALISM

Although our upright posture defines the human evolutionary lineage, trunk erectness developed early among primates. All major primate groups include species that sit or sleep in an upright position. On occasion, many primates assume an upright posture temporarily for the advantages it offers. Although birds, kangaroos, some lizards, and some dinosaurs assume a bipedal posture, all are quite different from that exhibited by humans.

Primate bipedalism usually takes the following forms: (1) Consistent bipedalism characterized by standing erect with straightened knees is practiced by humans. (2) Bipedal running occurs in many nonhuman primates. However, to compensate for the restrictions of the pelvis and hind limb musculature, they use a bent-knee gait. (3) Bipedal walking is less common among monkeys than among the great apes, whose gait, however, is a bent-knee gait. Only humans can stand bipedally erect for long periods of time. The distinguishing feature of human locomotion is that we are bipedal all the time as our normal mode of locomotion.

Because we are the only primate to have intensively taken up bipedalism, we are interested in how and why we did so. The anatomical changes necessary for bipedalism have been detailed in many places, and there has long been general agreement with Washburn’s (1971) scheme, presented in Table 1-1. There were major changes in the human lower limbs to accompany the shift to habitual bipedalism, not only in general skeletal proportions but also in the form of the muscles and in general limb functioning. Structural changes in the lower limbs include an elongated femur (thigh bone) and restructuring of the foot. Major changes in the lower limb skeleton include elongation of the bones (our lower limbs are longer than our upper limbs, the opposite of the great ape configuration), reorientation of bones, and different positioning of the muscles on the bones (Figure 1-4).

The human foot has shifted from the nonhuman primate pattern of a grasping organ to a weight-bearing platform. Major anatomical changes in the foot region occurred early in human evolution. The structure of the human foot indicates that it evolved from the kind of foot typical of apes and atypical of quadrupedal monkeys. The essential points are ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter One Trends in Human Evolution

- Chapter Two Fossils, Fossilization, and Dating Methods

- Chapter Three Determining Evolutionary Relationships

- Chapter Four Our Place in the Animal Kingdom

- Chapter Five Reconstructing Ancient Human Behavior and Social Organizations

- Chapter Six Early Primate Evolution

- Chapter Seven Basal Anthropoids, the Evolution of Monkeys, and the Transition to Apes

- Chapter Eight the Early Hominins

- Chapter Nine the Hominin Divergence

- Chapter Ten The Spread of Homo Beyond Africa

- Chapter Eleven Transitions to Archaic Homo Sapiens

- Chapter Twelve Neandertals and Their Immediate Predecessors

- Chapter Thirteen the Appearance of Homo Sapiens Sapiens

- Chapter Fourteen Conclusion?

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Human Evolution by Jeffrey K. McKee,Frank E. Poirier,W Scott Mcgraw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.