![]()

1

Most of What Architects, Urban Specialists, Policy Makers and Design Professionals Need to Know About Housing Can Be Learned from the Informal Sector

[I]t is pointless trying to decide whether Zenobia is to be classified among happy cities or among the unhappy. It makes no sense to divide cities into these two species, but rather into another two: those that through the years and the changes continue to give their form to desires, and those in which desires either erase the city or are erased by it.

Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino (p. 30)

The “housing problem” in developing countries is not actually a problem of missing or inadequate dwellings, and its solution is not merely the provision of shelters. Rather, it involves creating conditions in which people can live lives they have reason to value. Much as in Italo Calvino’s depiction of the invisible city of Zenobia, the solution to the housing problem lies in enhancing a settlement development process which, through changes over the years, gives shape to needs and desires. This can be viewed as either a self-evident statement, taken as a given by architects, urban planners and decision-makers, or as a complex argument that invites a careful examination of the relationship between these conditions and the role of all the professionals and decision-makers engaged in providing housing. In this chapter, I will argue that the latter is correct.

Sanchez’s Journey Toward a Meaningful Retirement

Mr Sanchez wears the hat and thick ruana (a garment commonly worn by peasants in cold Latin American regions) typical of rural areas as he pedals a decrepit bicycle loaded with vegetables that seem far too heavy for a man of his age to manage on the hilly roads of central Colombia. When I met him, he introduced himself using his two family names—as was once the custom of rural Colombians. Ruben Sanchez Rodriguez, a soft-spoken older man with dark skin and a few missing teeth, resembles many other immigrants in Bogotá and its neighbouring cities. While his house seems quite conventional, sadly, the story of the man and his house is not.

Mr Sanchez and his wife had never been outside their once paradisiacal northern Colombian home region when, six years ago, paramilitary militias threatened their lives and chased them off their property. Victims of an on-going conflict between leftist guerrillas and extreme-rightist paramilitary forces, Ruben and his wife abandoned their multi-acre property, valuable crops and cattle to follow in the footsteps of their two sons and daughter by migrating to Bogotá, the capital city and economic hub of Colombia. Instead of moving to the capital’s urban slums, however, the couple moved to a shantytown in Facatativá, a small city a few kilometres away.

Unlike many other rural migrants in poor countries, the Sanchez family was to stay in the slum for just a short time. Mr Sanchez applied for a housing subsidy and loan through a newly initiated municipal program and the family purchased a 40 m2 unit on an 80m2 plot in a new Facatativá settlement. The house was only partly finished and was delivered with no floors or ceilings, wall finishes, basic appliances and with doors unpainted. It had neither hot water nor a cistern to mitigate the effects of frequent water supply failures.

The two-story house was good, however, Mr Sanchez recalled. It had running water for most of the week, a sewage system and electricity and telephone service. With two bedrooms and an inside bathroom, the new brick house was somewhat small for the elderly rural couple, who dreamt of reuniting their extended family. It was particularly cold during the rainy season for a couple used to the northern region’s tropical weather. An agricultural job near Facatativá allowed Mr Sanchez to save enough money to finish the house and build a backyard extension. Upgrading the house and building the extension was easy—like most men from the country, he had basic construction skills and was able to get some “young men from the region” to help him with the concrete structure, plumbing and electricity. Within a couple of years, the Sanchez family doubled the size of the house.

The extension proved to be very important for Mr and Mrs Sanchez. They built small rooms for their three grandchildren, and an extra bathroom. They are proud to say that their extended family now visits them quite often and their grandchildren stay with them on holidays. They also built a solarium whose translucent corrugated roofing material raises the temperature in the house (see Figure 1.1). “This is the space where my wife and I like to spend our free time,” Mr Sanchez says proudly. “It is a small piece of the tropical home that we lost six years ago.” Mr and Mrs Sanchez and their family lost the valuable assets gained over a lifetime, and will probably never be able to return to their farm or hometown. They also lost the place where their children were born and raised. They found themselves internally displaced at an age when being forced to start a new life from scratch is demeaning. Despite this, and unlike many millions of families in developing countries, Ruben and his wife were relatively lucky. They escaped, unharmed, a war that has claimed thousands of lives, and avoided the fate of the thousands of rural migrants who find themselves living in urban slums for several generations, where washrooms are public—if they exist at all—and obtaining drinking water means walking long distances. Unlike many other elderly rural peasants who are unable to find a job in Bogotá, they did not end up begging for money in an urban park or on a busy downtown street. After their humiliation and suffering, a housing solution made an important contribution to the resumption of a meaningful life which they value profoundly; one in which they can be useful to their family by helping to raise their grandchildren.

FIGURE 1.1 Mr Sanchez spends most of his free time in this solarium, which reminds him of the home from which he was forcibly evicted. While figures of internally displaced persons (IDP) can vary greatly from one study to another, it is estimated that in 2005 almost two-thirds of the world’s IDPs were Colombian.

Slums and Informal Settlements: Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution?

There are various types of slums and informal developments within cities and across regions and countries. It is generally accepted, however, that they are the most tangible representation of qualitative and quantitative housing deficits and evidence of social inequalities and injustices, including segregation, exclusion, marginalization and violation of human rights. The UN-Habitat Global Report on Human Settlements 2009 estimated that close to 1 billion people—equivalent to 36.5% of the world’s urban population—live in slums.1 This figure rises to 62% in Sub-Saharan Africa and 43% in South Asia, and is expected to increase to 2 billion people by 2030.2

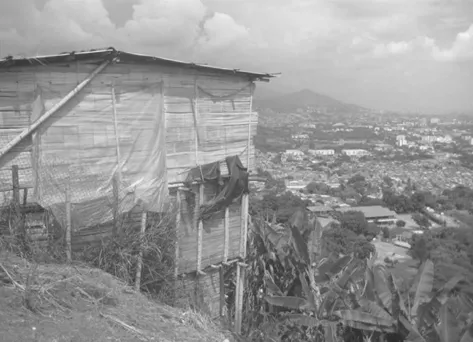

Whereas there are ambiguous and controversial definitions of urban slums and other forms of informal settlements, it has been found that they are characterized by increased physical, social and economic vulnerabilities (see Figure 1.2). Chapter 7 will explore the causes of such vulnerabilities, but for the moment let’s just state that they represent limited or insufficient access to three types of resources: “hard” resources, such as income, safe shelter, savings and food, and “soft” resources, such as education, insurance, political representation and security, along with services such as sanitation, clean water, roads, electricity, public transportation and health care. Slum dwellers and residents of informal settlements are therefore more susceptible to damage in the wake of natural disasters triggered by landslides, floods, earthquakes and fires (see Figure 1.3), to diseases and child mortality (resulting from exposure to toxic and industrial waste, indoor air pollution, polluted water, etc.) and to violence and crime. They typically rely on informal work, and have unclear land tenure and property rights, increasing their vulnerability to social injustices.

FIGURE 1.2 Informal settlements are characterized by increased vulnerabilities. This house in an informal settlement in Cali, Colombia, is at high risk of being destroyed by landslides.

It is not surprising, therefore, that slums are often seen as limiting the human potential of their residents3 and causing significant public health problems. It is estimated that half of the population of Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean suffer from diseases linked to inadequate water and sanitation.4 Despite a recent worldwide trend recognizing the merits of urban agriculture, the increased presence of animals in urban slums is also frequently associated with infectious diseases that undermine public health.5 Slums are also accused of reducing the efficiency of cities and the economic growth of countries. It is estimated, for instance, that every GDP dollar generated in Chile’s capital, Santiago, requires 60% more energy than a GDP dollar generated in Helsinki, Finland.6 More surprisingly, some authors have argued that, contrary to common belief, living in slums is also a financial burden to their inhabitants. In a study conducted in the mid-1980s, housing specialists...