- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ethics and Public Administration

About this book

"Ethics and Public Administration" refutes the arguments that administrative ethics cannot be studied in an empirical manner and that empirical analysis can deal only with the trivial issues in administrative ethics. Within a theoretical perspective,the authors qualify their findings and take care not to over-generalise results. The findings are relevant to the practice of public administration. Specific areas addressed include understanding public corruption, ethics as control, and ethics as administration and policy

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One |

The Problem—Understanding Public Corruption

1 |

Public Attitudes toward Corruption: Twenty-five Years of Research

Kathryn L. Malec

Several definitions of political corruption have been proposed, and generally can be classified according to three criteria: definitions based on legality, definitions based on the public interest, and definitions based on public opinion…. The definition of political corruption based on legalistic criteria assumes that political behavior is corrupt when it violates some formal standard or rule of behavior set down by a political system for its public officials…. Definitions of political corruption based on notions of the public or common interest significantly broaden the range of behavior one might investigate…. The researcher has the responsibility of determining what the public or common interest is before assessing whether a particular act is corrupt. A third approach to the definitional problem suggests that a political act is corrupt when the weight of public opinion determines it so. (Peters and Welch 1978a; 974–75, emphasis added)

Varieties of Corruption Definitions

Over the past twenty-five years, official corruption has frequently been a topic of public concern. Scandals such as Watergate, Abscam, the Iran-Contra Affair, and their state and local counterparts have lead to prosecutions and the ouster of elected officials, and legislatures have often responded by creating or strengthening official misconduct and campaign finance statutes. At the same time, specialists in political science and public administration have sought to increase understanding of corruption as a form of political behavior and as a management problem. As a result of this increased attention, there is now an extensive body of research literature documenting the many forms corruption has taken (see, for example, Malec and Gardiner 1987) and analyzing the philosophical issues involved in labeling behaviors as ethical or unethical.

As John G. Peters and Susan Welch indicated, corruption scholars have defined their subject matter in different ways. Joseph S. Nye (1967, 419) defines official corruption as “behavior which deviates from the formal duties of a public role because of private-regarding (personal, close family, private clique) pecuniary or status gains; or violates rules against the exercise of certain types of private-regarding influence”. Examples of behavior violating “formal duties” include bribery (use of compensation to pervert the judgment of a person in a position of trust); nepotism (bestowal of patronage positions by reason of ascriptive relationships rather than merit); misappropriation (illegal allocation of public resources for private uses); and willful failure to enforce laws or invoke sanctions that are appropriate to a situation. This definition assumes that behavior is corrupt only when it violates a formal standard or rule, which can happen only if legislators have labeled it corrupt.

Other scholars have built their definitions around the effects of corruption. Rogow and Lasswell (1963, 132–33) argue that

a corrupt act violates responsibility toward at least one system of public or civic order and is in fact incompatible with (destructive of) any such system. A system of public or civic order exalts common interest over special interest; violations of the common interest for special advantage are corrupt.

That is to say, corruption exists if the public trust or good is betrayed whether or not a violation of legislated standards transpires.

Public Attitude-Centered Corruption Research

This chapter will review and synthesize research that has used elite and mass interview techniques to explore public attitudes about official corruption. Barry Rundquist and Susan Hanson (1976, 2–3) provide a clear focus for this analysis: “Political corruption [involves] behavior by an individual or group (party, administration) which violates citizens’ conceptions of acceptable official behavior within their political community.”

Arnold Heidenheimer (1970) notes that corruption can be “black,” “white,” or “gray.” “Black” corruption involves actions that are judged by both the public and public officials as particularly abhorrent and therefore requiring punishment. “White” corruption might be political acts deemed corrupt by both the public and officials, but not severe enough to warrant sanction. “Gray” corruption involves those actions found to be corrupt by either one of the groups, but not both. The importance of such variations in attitudes is clear: “What may be corrupt to one citizen, scholar, or public official is just politics to another, or discretion to a third” (Peters and Welch 1978a, 74). If a society defines certain behaviors as corrupt and then supports the legal system in enforcing that definition, then, and only then, will the legal system be able to enforce ethical standards effectively and over a long period of time. However, if a society defines certain behaviors as not corrupt but the legal system defines them as corrupt, the legal system will be unable to enforce legal standards of ethical behavior.

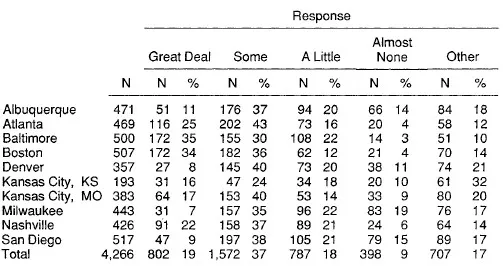

Table 1.1

Citizens’ Estimates of the Extent of Bribery and Other Illegal Activity in City Government

Source: David Caputo, Urban America: The Policy Alternatives (1976, 65). Data were collected as part of the Urban Observatory Program funded by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. The question asked was “In some cities, officials are said to take bribes and make money in other ways that are illegal. In other cities, such things almost never happen. How much of that sort of thing do you think goes on in [this city]?”

A major problem in corruption research has been the lack of reliable data to indicate the prevalence of corruption. Media reports and indictments may only indicate whether or how frequently journalists or prosecutors have gone looking for corruption, rather than how often it occurs (Malec and Gardiner 1987). However, a comparative study of ten major cities undertaken in 1970 by the National League of Cities attempted to measure prevalence by asking several questions that focus on public perceptions of the extent of political corruption (Caputo 1976, 63–66). When citizens were asked about the honesty of local public officials, their responses were, for the most part, relatively favorable. Although there was some variation among cities as shown in Table 1.1, about one-fifth of the respondents from all ten cities thought that local government officials were less honest than most other people; two-thirds thought that government officials were about the same as most other people. When asked how many public officials “take bribes and make money in other ways that are illegal,” 56 percent responded “a great deal” or “some.”

Hierarchies of Seriousness

Analogous to Heidenheimer’s scale of black, gray, and white corruption, a series of survey research projects have sought to construct hierarchies suggesting the factors that make some behaviors more or less “corrupt” in the eyes of the public. It is apparent from the research by Beard and Horn (1975), Gardiner (1970), Gibbons (1989), Howe and Kaufman (1979), Johnston (1983), Joseph (1988), Lane (1962), Peters and Welch (1978)b, and Smigel and Ross (1970) that people judge the severity of corruption by who is involved and what is done. Over and over, the research found that respondents judged elected officials more severely than they judged appointed officials; judges more severely than police officers; bribery and extortion more harshly than conflict of interest, campaign contributions, and patronage; and harmful behavior more harshly than petty behavior.1

As Lane (1962) discovered, a majority of the fifteen working- and lower-middle-class men of an Eastern seaboard city whom he interviewed believed that politics and corruption go hand-in-hand. It was not surprising to those interviewed that politicians would cheat a little when it came to campaign contributions, conflict of interest, and special favors. Beard and Horn’s (1975) study of fifty congressmen of the Ninetieth Congress found that a number of congressmen believed that “it is none of our business” to interfere with someone’s personal choices. If a fellow congressman accepted an honorarium for a speech, it was his business and no one else’s. If a politician had a secretary who could not type, it was his business and no one else’s. And if a politician hired his wife to be his office manager, it was his business and no one else’s. Smigel and Ross (1970, 7) determined in their study of crimes against bureaucracy that for many, “theft appears to be easier to excuse when the victim has larger assets than the criminal, as exemplified by the Robin Hood myth.” Therefore, size and the accompanying characteristics of impersonality, bureaucratic power, and red tape were the main reasons given for stealing from large organizations such as corporations and government.

Gardiner (1970) expanded the study of public attitudes toward corruption by surveying attitudes of non-elites in a small Eastern city (“Wincanton” or Reading, Pennsylvania) with a long history of political corruption and influence by organized crime. He asked whether widespread local corruption could be attributed to the preferences and attitudes of city residents by examining the question of public acceptance of official misconduct, especially in relation to nonenforcement of laws against gambling. While interviewing 180 randomly selected residents, Gardiner found that upper-status residents, who were better informed about politics and corruption, were less tolerant of official corruption. Those who gambled and those who had spent most of their lives in the city were most tolerant of gambling. However, in respect to acceptance of corruption, those who had spent most of their lives in Wincanton were less tolerant of corruption than those who had lived elsewhere. In addition, the study found relatively lower levels of tolerance of corruption among younger respondents and among those with more education.

In their analysis of responses by state senators to a series of items concerning ten hypothetical actions by public officials, John G. Peters and Susan Welch found that situations judged most corrupt by legislators were those that involved clearly illegal activity and/or direct personal financial gain by the public official: the driveway of the mayor’s home being paved by the city crew; a public official using public funds for personal travel; a state assembly member, while chairperson of the Public Roads Committee, authorizing the purchase of land he had recently acquired; a legislator accepting a large campaign contribution in return for voting “the right way” on a legislative bill (Peters 1977; Peters and Welch 1978a, 1978b, 1980; Welch and Peters 1977, 1980).

In the Peters and Welch survey, minor forms of influence peddling were least likely to be regarded as corrupt: a public official using his influence to get a friend or relative admitted to law school, or a congressman using seniority to obtain a weapons contract for a firm in his district. A variety of conflict-of-interest situations produced the lowest consensus among the respondents: a judge hearing a case concerning a corporation in which he has $50,000 worth of stock; a presidential candidate who promises an ambassadorship in exchange for campaign contributions; a secretary of defense who owns $50,000 in stock in a company with whic...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Bureaucracies, Public Administration, and Public Policy

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Contributors

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part One: The Problem—Understanding Public Corruption

- Part Two: Ethics as Control

- Part Three: Ethics as Administration and Policy

- Part Four: Conclusions

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ethics and Public Administration by H George Frederickson,John A. Rohr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.