![]()

Part I

Fundamentals

Construction claims, and BIM/VDC

![]()

1 Traditional construction claims

A review of existing literature concerning traditional construction claims and disputes reveals a path that is broad, clearly marked, and very well-trodden. Accordingly, the sections that immediately follow are intended to provide the design, engineering, construction, or construction law beginner with an introductory survey course in the broad topics of this established field. In simplistic terms and without a hint of cynicism, construction disputes are about money and why one party feels they are entitled to compensation from another party. The central issues of claims can vary widely from technical issues, to matters of law, to legal standards of care, and so on. As such, this chapter will briefly and succinctly convey the essence of typical construction claims and the monetary damages associated with each.

The goal of this chapter is to present a practical outline of a construction claims taxonomy that one might more easily recall when considering BIM and VDC issues. Whereas entire books might be (indeed have been) dedicated to individual claims topics, the intent here is to provide a general survey overview which is used as a basis for analysis in the chapters that follow. For example, while the concept of “delay” will be summarized, additional discussion of “concurrent delay” and the “apportionment of delay” will not be.

At the highest setting of the blade, this claims taxonomy will be divided into three primary segments: contractor claims against owners, owner claims against contractors, and claims in tort. The summaries within each segment will be drawn with single lines and will outline general shapes. Footnotes, the References and the List of cases will provide a gateway to further detail, nuance, and interpretation. Additionally, the summaries favor those aspects of claims which could find themselves first in line for renewed consideration under the lights of BIM and VDC. For example, defective and/or deficient construction documents versus differing site conditions.

Finally, in keeping with a survey methodology a brief note on general context and vocabulary: While non-traditional contracting methods including design–build (DB), integrated project delivery (IPD), and public private partnerships (P3s) continue to receive consideration by contracting parties (and in the case of P3s growing instances of legislative support1 and implementation2), the typical construction claims analyzed here are rooted in the world of traditional design–bid–build (DBB) contracts. This is a contract framework wherein the owner has a contract with the architect or engineer to design the work, and a separate contract with a contractor to construct the design. Additionally, the general use of “contract” may include examples or discussion of private and/or government contracts, and/or any number contractual arrangements, including, for example, lump sum payment, guaranteed maximum price, and so on. Likewise, “design professional” may be used to refer to architects and/or all form of consulting engineers (mechanical, electrical, civil, etc.) with “contractor” similarly referring to a general contractor or construction manager of various type, unless specifically noted otherwise.

1.1 Contractor claims against owners

Claims on a construction project often arise in the contract for construction between the contractor and the owner. Thus, contractors and owners initially look to the four corners of the page in establishing the terms for the resolution of their differences. In doing so, it is important to appreciate that the page includes not only express clauses and provisions, but equally influential implied terms and industry custom. The well-crafted construction contract is no mere napkin scribble. As described by construction law scholar and practitioner James Arcet, construction contracts reflect multiple facets of the modern condition in regards to design and construction. Building codes, insurance, licensing and bonding, a long history of common law perspective on damages – each has a place.3 Arcet also notes that construction contracts are influenced primarily by two types of knowledge, “construction knowledge” and “legal knowledge.” The former privileges the holder in negotiating the requirements of the plans and specifications describing the work, the latter favors an understanding and anticipation of how contract terms have been interpreted by the courts.4 While there may exist a current dearth of case law dealing specifically with BIM and VDC, the fact that these technologies and processes can fundamentally influence construction – both substantively with regards to means and methods, and procedurally in terms of typical duties, obligations or implied warranties – suggests that practical knowledge about both will well serve any party to a modern construction contract.

Contractors typically pursue claims against an owner under the following classifications: scope changes, acceleration claims, delay claims, and disruption claims. (Also included in this list are payment claims and termination claims, but for the summary purpose of this chapter a discussion of such claims is excluded.). These claims types often correspond loosely, if not directly, to given section headers or sub-headers in the written contract itself.5 These classifications are not always mutually exclusive, hence a contractor’s claim against an owner might include, for example, both a delay claim and a disruption claim.

As noted above, while claims are often pursued under specific contract clauses, there are also non-explicit, or implied, warranties in each construction contract including the contractor’s workmanlike performance and the owner’s implied warranty of contract documents. These doctrines establish, respectively, that the contractor has a duty to perform the work in accordance with the level of skill and care expected of the average qualified contractor in a given location, and that the owner will supply the contractor with drawings and specifications that are accurate, correct, and buildable. Implied warranties will receive further elaboration and consideration in later sections.

A brief summary of the typical construction claims brought by a contractor against an owner are presented below. These summaries will serve as the referential basis to more in-depth BIM and VDC analysis in subsequent chapters and sections.

1.1.1 Scope changes – overview

Defining exactly what work the contractor is going to do in fulfilling their obligations under the contract documents – the scope of work – is typically an extremely complex endeavor, some even suggesting impossible.6 It usually requires the design professional to prepare detailed drawings (often voluminous) describing the quantitative aspects of the work, as well as detailed written specifications (often voluminous) describing the qualitative aspects of the work. Together, the drawings (graphic symbolism) and specifications (narrative text) set forth the requirements for the construction of the design.

The drawings and specifications must in turn be coordinated with the requirements of applicable building codes and industry standards. As anyone who has participated in a large design and construction project knows, it would not be unreasonable to imagine these documents filling a room, or even multiple rooms. In many cases the shear administrative task of keeping the specifications and drawings coordinated within and between themselves can be overwhelming.

It is from this proverbial mountain of information that the contractor must infer just what the expected end result is and how to get there on time and within budget. Hence, the colliding realities that serve as the nexus of claims. One variable includes extensive, highly detailed, interconnected and interdependent specifications, drawings, building codes and industry standards as prepared by the design professional. A second variable requires a contractor to interpret the aforementioned network of information. Both of which must contend with the inevitability of change on design and construction projects. Needless to say, these conditions provide a healthy environment for the birth of scope changes. Indeed, some consider a 5 to 10 percent cost growth due to scope changes within an acceptable normal range.7

In some instances scope changes are the result of explicit instructions by the owner. Such changes are referred to as directed changes. A simplistic example is, “Please add another floor to the parking garage that was not part of the original plan.” Construction contracts often contain “changes” clauses that give the owner the flexibility to make such changes and formalizes the administrative processes of effecting the change. These changes clauses will typically define the type and timeliness of notice that must be given by the owner, and the amount of time the contractor has to respond with an estimate for the requested change. Typically, if the owner and contractor follow the process established by the changes clause, the owner achieves their desired outcome and the contractor receives an equitable adjustment to the contract cost and/or schedule. If, however, the owner and contractor cannot agree on the exact scope of work for the directed change and the related costs for the change, a claim may ensue.

In contrast with a directed change is the concept of a constructive change. In a constructive change claim a contractor and an owner may have a disagreement over what the original contract documents actually show, say, or mean. Or, there may be events or conditions such as improper owner rejection of work, or excessive testing requirements that may result in a scope change. Thus, a constructive change is conduct (either action or inaction) by an owner that is not a formal change order (a directed change) but which has the effect of causing the contractor to perform the work in a manner different from what the terms of the original contract required. Furthermore, a constructive change does not necessarily mean there is a change to the character and quantity of the work.8

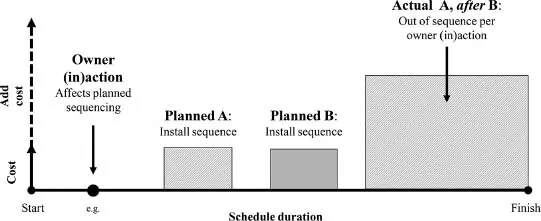

In contrast to the previous example of an owner directed change “add another parking level,” a constructive change might take the form of an owner action (or inaction) around sequencing of work. For example, consider a construction drawing showing elements A and B. The contractor reviews the drawings and, bringing to bear their expertise in the means and methods of construction, prepare a bid to complete the scope of work for installing A and B. Their bid includes plans to install A before B. The owner accepts the bid and the contractor begins the work. However, subsequent actions or inactions on the part of the owner result in the contractor being forced to install B before A. The effect of forcing the contractor to alter his planned sequence or duration for installing A before B may cause the contractor to experience cost and/or schedule inefficiencies without altering the scope of work originally defined by the contract and used as the basis of the bid, that is, installing A and B (Figure 1.1).9

Generally accepted theories by which a contractor might make a claim for a constructive scope change include, amongst others, defective and deficient contract documents, and implied warranties and duties. In the interest of a longer term focus on BIM and VDC issues, these two items are summarily reviewed here.

Figure 1.1 Constructive change: altering...