- 204 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

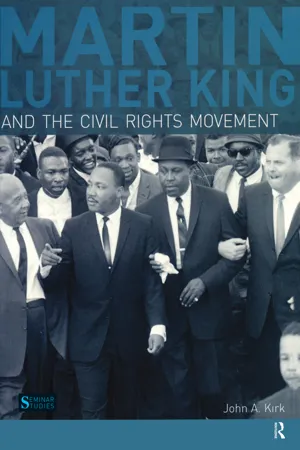

Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement

About this book

Martin Luther King, Jr is one of the iconic figures of 20th century history, and one of the most influential and important in the American Civil Rights Movement; John Kirk here presents the life of Martin Luther King in the context of that movement, placing him at the center of the Afro-American fight for equality and recognition.

This book combines the insights from two fields of study, seeking to combine the top down; national federal policy-oriented approach to the movement with the bottom up, local grassroots activism approach to demonstrate how these different levels of activism intersect and interact with each other.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Civil Rights Movement by John A. Kirk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Background

Introduction: Martin Luther King, Jr.: Saint, Sinner, or Historical Figure

Early histories of the civil rights movement that appeared prior to the 1980s were purely biographies of Martin Luther King, Jr. Collectively, these works helped to create the familiar ‘Montgomery to Memphis’ narrative framework for understanding the history of the civil rights movement in the United States. This narrative begins with King’s rise to leadership during the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama, and ends with his 1968 assassination in Memphis, Tennessee.

Since the 1980s, a number of studies examining the civil rights movement at local and state levels have questioned the usefulness and accuracy of the King-centred Montgomery to Memphis narrative as the sole way of understanding the movement. These studies have made it clear that civil rights struggles already existed in many of the communities where King and the organization that he was president of, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), ran civil rights campaigns in the 1960s. Moreover, those struggles continued long after King and the SCLC had left those communities. Civil rights activism also thrived in many places that King and the SCLC never even visited.

Southern Christian Leadership Conference: A black minister-led civil rights organization founded in 1957 and headed by Martin Luther King, Jr. from 1957 to 1968.

The historiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the civil rights movement, as that term itself implies, has consequently developed in two distinct strands. The literature is made up, on the one hand of biographies of King in the ‘Montgomery to Memphis’ mould, and on the other of histories of the civil rights movement that have increasingly tended to frame that movement within the context of a much larger, ongoing struggle for black freedom and equality unfolding in the twentieth century at local, state, national and even international levels.

Partisan movement activists have played their own role in reinforcing the idea that there is a division between the ‘man and the movement’. Notably, there is the over-used quote from Ella Baker, a former SCLC staff member, who, disillusioned with the organization and King, went on to become instrumental in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), that ‘The movement made Martin rather than Martin making the movement.’ Contrast this with the claim by C. T. Vivian, a stalwart SCLC staff member and, like King, a black Baptist minister, that ‘Man, Dr. King was the movement.’

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee: A student-led civil rights organization that grew out of the 1960 sit-ins.

The revelation of personal fallibilities have challenged King’s saint-like image in early historical works and in the popular imagination. In 1989, Ralph D. Abernathy, King’s closest friend and confidant, revealed in his autobiography a number of salacious details about King’s alleged affairs. In 1990, Claybome Carson, director of the King Papers Project at Stanford University, broke the news that King had plagiarised significant portions of his PhD thesis while at Boston University. Much controversy and debate has raged on these subjects since.

Yet at the same time, King’s sanctification as an American hero has continued. Since 1986, every third Monday in January has been celebrated as a federal Martin Luther King, Jr. Day holiday. In 2011, the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial was unveiled on the National Mall in Washington DC. King is the first and, to date, only black American to have been honoured by a national holiday and a national monument. Hundreds of streets in the United States have been named, or renamed, after him.

The central focus of this book is not to cast King as a saint or a sinner, nor as a simplified national hero, but, by using the available historical evidence, to fully assess his role and influence as a historical figure. In utilizing the ‘Montgomery to Memphis’ narrative, it does not look to simply repeat earlier versions of it, but, rather, to rethink and recast it within the light of recent historical scholarship. This study differs from other, particularly shorter, studies of King, in that it locates him firmly within the context of other leaders and organizations, voices and opinions, and tactics and ideologies, which made up the movement as a whole.

There were, this book argues, four distinct stages to King’s development as a civil rights leader. The first stage was King’s rise to leadership during the 1955–1956 Montgomery bus boycott. During the boycott, King used his status as a black southern Baptist minister to help mobilize the black community. He harnessed the black church both as a spiritual base for legitimizing and shaping the nature of the protest movement, and as a physical base for mass meetings and information dissemination.

The second stage of King’s career, stretching from the Montgomery bus boycott to the 1963 Birmingham Campaign, saw King struggling to translate the mass black community activism of the Montgomery bus boycott and the idea of non-violence into a coherent strategy for social and political change. To that end, King, along with other movement activists, helped to found the SCLC. However, early efforts to expand mass black activism through bus boycotts and voter registration campaigns met with little success. Events elsewhere, unfolding largely independently of King and the SCLC, fared much better.

The 1960 student sit-in movement led to the formation of a new student-oriented organization in SNCC and forced concessions for the desegregation of public and private facilities in a number of communities. The 1961 Freedom Rides were instigated by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and forced federal intervention to uphold civil rights in interstate transportation facilities. The sit-ins and the Freedom Rides led the way in demonstrating how non-violent direct action might effectively be applied to bring about social change.

Sit-In: An act designed to directly challenge segregation laws and to force businesses to consider the economic viability of practising segregation.

Freedom Rides: Testing of desegregated bus terminals initiated by CORE in 1961.

King tried to capitalize on these developments in 1961–1963 in two community-based campaigns in Albany, Georgia, and Birmingham, Alabama. Although King and the SCLC’s campaign in Albany at the end of 1961 and the beginning of 1962 encountered a number of difficulties, it proved a vital learning experience in running a far more successful campaign in Birmingham in 1963.

Congress of Racial Equality: One of the ‘Big Six’ civil rights organizations, founded in 1942 and a pioneer in non-violent direct action.

In Birmingham, King and the SCLC developed a strategy of short-term black community mobilization in non-violent direct action demonstrations that successfully forced concessions from whites for civil rights at a local level and engaged support and action from federal government for civil rights at a national level. Historian David J. Garrow notes that the Birmingham strategy marked a significant break from King’s earlier attempts to use ‘non-violent persuasion’, relying on the moral aspects of non-violence to persuade whites to instigate racial change, to a use of ‘non-violent coercion’ to force change through non-violent direct action demonstrations.

Civil Rights Act of 1964: Required the desegregation of public facilities and accommodations and a range of other pro-civil rights measures.

The third stage of King’s career, and his most successful, unfolded between the 1963 Birmingham Campaign and the 1965–1966 Chicago, Illinois, Campaign. During this time, King and the SCLC attempted to repeat the strategy of the 1963 Birmingham Campaign in other communities.

Segregation: The enforced separation (sometimes legally mandated, sometimes not) of facilities and resources by race.

Of these campaigns, King and the SCLC’s Selma Campaign was by far the most successful, engaging the highest level of public attention, of northern white support, and of federal intervention and action. Following on from the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which had legislated an end to segregation in public facilities and accommodations, President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced and oversaw the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which removed obstacles to black voting rights and provided active federal assistance to black voters.

Voting Rights Act of 1965: Act outlawing discriminatory voting practices such as literacy tests and establishing federal oversight of administering elections.

The fourth stage of King’s career is the most complex and generally the least understood. It began with the 1965–1966 Chicago Campaign and ended with King’s assassination in Memphis in 1968. During this period, King was forced to re-evaluate the Birmingham strategy in the face of a rapidly changing struggle for black freedom and equality.

With the goal of legislation to compel desegregation and to enforce the black franchise achieved, King and the civil rights movement looked to consolidate these victories while seeking to address new challenges. A number of urban riots in black ghettos of the West and North of the United States between 1965 and 1967 highlighted the problems faced by blacks outside of the South, where King and the SCLC had been predominantly based.

Black Power: Slogan popularized by Stokely Carmichael in 1966 and often associated with black militancy, black nationalism and black armed self-defence.

Vietnam War: A war between the communist North Vietnam and the South Vietnamese regime which the US backed with political and military support from 1955 until its collapse in 1975.

The popularization of the ‘Black Power’ slogan emerged from the experiences of SNCC workers in the rural counties of Alabama and Mississippi, areas where King and the SCLC’s influence was also slight, since the Birmingham strategy was focused more on towns and cities. Amid these changes, the Vietnam War increasingly overtook civil rights as the most important domestic issue in the United States and the anti-war movement began to sap civil rights movement activists and volunteers.

The urban riots, the rise of Black Power, and the anti-war demonstrations, all played their part in prompting a white conservative political backlash to the perceived excesses of liberalism, which conservatives believed was the cause of these developments. King, the SCLC, and the civil rights movement as a whole, were challenged to move beyond desegregation and black enfranchisement to tackle the fundamental economic problems that underpinned black powerlessness and to engage with larger unfolding social and political developments.

King responded to these developments in a number of ways. He tried to tackle the problems faced by urban blacks by implementing the Birmingham strategy of non-violent direct action demonstrations in Chicago. He sought to temper Black Power’s anti-white rhetoric and advocacy of black nationalism, black separatism, and black armed self-defence, by insisting that integration and non-violence were still relevant to the struggle for civil rights. He joined the anti-war movement to oppose the United States’ actions in Vietnam and he attempted to fuse the energies of the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Series Page

- Contents

- Author's acknowledgements

- Publisher's acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chronology

- Who's who

- Glossary of terms and organizations

- Map

- Further reading and primary sources

- Part 1 Background

- Part 2 King and a Fledgling Movement, 1955–1960

- Part 3 King and a Developing Movement, 1960–1963

- Part 4 King and an Expanding Movement, 1963–1965

- Part 5 King and a Fractious Movement, 1965–1968

- Part 6 Documents

- Index