![]()

1

Introduction

Every four years, or so it seems, the population of the United States gets to revisit the concept of international trade. This is typically inspired by the presidential election cycle and whether the combatants are pro-or anti-trade. The frequency of such learning opportunities might be read as an index of the inability of US politicians to understand trade theory (likely, given the claims that are made), the importance of trade to US voters (also likely, given the growing complexity of the global economy) or perhaps both. Who could forget the arguments of Ross Perot, running as an independent in the 1992 presidential election contest and his claims of a “giant sucking sound”, representing the movement of US jobs south of the border into Mexico that would follow passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement. In the current edition of this program we are reminded by Donald Trump that the US is a loser in terms of trade and that the only way to make the country “great again” is to allow him to renegotiate our trade deals with foreign partners. Meanwhile, Hilary Clinton and Bernie Sanders are battling over what kinds of trade agreements, if any, the United States should embrace. For them, the question is not that the US always loses through trade, but that the impacts of foreign trade are unevenly distributed across American workers. On the other side of the Atlantic, the benefits of trade are also being questioned as the UK voted to exit the European Union after decades of trade expansion with its continental neighbors. The so-called “Brexit” has generated great political and economic uncertainty and, perhaps, “the end of an era of transnational optimism” (Donadiojune, 2016).

What is trade, why do we trade and why do some groups rather than others benefit or lose as a result of trade? These are important questions that we explore throughout this book. Trade occurs when firms or consumers or even the government in one country purchase goods or services that are produced, in whole or in part, in other countries. The goods that we produce in the United States and sell in foreign markets are counted as US exports. The goods and services produced outside the US but purchased and consumed in this country are US imports. Firms and consumers in one part of the world purchase goods and services made elsewhere for a number of reasons. Perhaps the most obvious of these is that some commodities cannot be produced in all places. Certain fruits or vegetables can be grown only in locations with specific climate conditions. Other commodities require particular skills for their production that are found in relatively few countries. Advanced biotechnology products, for example, may be produced only in those places where workers and firms have the necessary capabilities or expertise. Yet, these firms produce drugs and medicines that can save lives across the world as a whole. In another case, consumers in one country might prefer a brand of automobile made in another country. Trade allows the consumer’s love of variety to be satisfied. Finally, some countries are much more efficient than others at producing certain types of commodities. By exploiting variations in relative efficiency for different goods in different countries, trading partners might all benefit from trade.

If trade is beneficial for trading partners, then why are so many people angry about the impacts of trade? There are a number of answers to this question. First, even though free trade generates economic gains, how those gains are distributed is important. By altering international commodity prices, some countries might be able to capture more of the gains than others. Second, there are costs to trade as well as benefits. For example, when a high-wage economy such as France imports goods made by low-wage workers in the rest of the world, low-wage workers in France face lower wages and potential job-loss. At the same time, high-wage workers in France might see their wages increase as a result of international market integration. For France as a whole, trade might mean a reduction in the price of many goods, but this is little solace for workers who lose their jobs to rising imports. Third, by fueling growth, trade is often linked to environmental pollution and climate change. Many who protest trade are focused on the negative consequences of production within the market system. Finally, some protest trade because they may not understand the complexity of production networks that link various countries. Thus, when a country such as the United States is running a trade deficit, a higher value of imports relative to exports, some will complain about the unfair nature of global trade, or about one-sided trade deals that hurt US labor. The usual refrain is to “buy American”. However, what many do not realize is that in today’s global economy, many “American” firms have shifted production out of the US only to set up factories in foreign locations. Thus, many of the imports that drive the US trade deficit are commodities made by US firms in other countries. It is not clear that moving such production back to the US would generate net benefits for the US economy. Let us briefly explore the case of Apple and production of the iPhone.

Apple’s iPhone is a commodity produced by workers spread across many countries of the world. The iPhone design and iOS software are developed at Apple’s headquarters in Cupertino, California. Key components of the iPhone are sourced from other firms in the United States, Europe and East Asia. All these components are assembled into the iPhone in the Chinese factories of the Taiwanese electronics firm Hon Hai Precision Industry, better known to many by the trade name Foxconn. It is estimated that Apple employs about 110,000 workers around the world, approximately 40% of that number in retail activities, with about the same proportion of its overall workforce located outside the United States. Duhigg and Bradsher (2012) of the New York Times suggested that approximately 700,000 people develop and assemble Apple products in firms linked to Apple through contracting and sub-contracting relationships around the world. Indeed, Foxconn employs over 1 million workers at its Chinese factories alone. Though the number of Foxconn workers employed directly on the iPhone is unknown, estimates put that number at well over 300,000.

The iPhone is a classic example of what we imagine as a “global commodity”, a product designed, manufactured and assembled in different parts of the world before being sold almost everywhere. Why did Apple adopt this global style of organizing its operations as opposed to producing the iPhone exclusively in the United States? The answer is that it is much more cost effective for Apple to exploit international variations in skills and prices of inputs, especially labor, than to produce its products in a single country, even after the cost of transportation is factored in. Most of the jobs associated with iPhone production are those that involve the assembly of components into the finished product. These jobs are relatively low-skilled and thus it makes sense for Apple to locate such production in emerging economies like China, where low-skilled workers are abundant and paid relatively low wages. But this is not the whole story. It is widely acknowledged that few countries can match the manufacturing flexibility of the Chinese economy. With vast numbers of workers distributed across different kinds of manufacturing operations, China offers advantages to firms operating at many different points along the supply chains (the networks of firms) that produce so much of the world’s output.

How does the production activity of a corporation like Apple impact trade? Many iPhones, once assembled, are shipped from China to the United States and to other countries around the world. These shipments represent exports from China and imports to the countries where they end their journey. In 2009, the value of iPhone exports from China to the United States was estimated at US$1.9 billion (Xing and Detert, 2010), contributing significantly to the US trade deficit with China. Thus, buying a smartphone from a US corporation like Apple would not help the US trade deficit and it might generate more jobs in foreign countries than in the United States. Most all trade economists would still insist that this global organization of production is a net positive for the US economy, and that it is not in the country’s best interests for the jobs in the Foxconn plants within China to return to this country. Low-wage workers in the US are likely to dispute these claims, and environmentalists might argue that there are additional costs to trade. While the net effect of Apple’s imports is still being debated, what seems clear is that trade has grown exponentially in the past few decades, driven by the global activities of companies like Apple.

The Growth of Trade

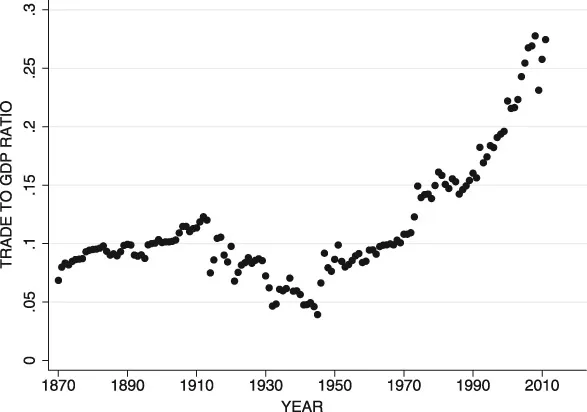

Figure 1.1 maps the ratio of trade ((imports + exports)/2) to gross domestic product (GDP) for the world economy since 1870. GDP measures the total value of goods and services produced within a given year (in this case for all countries in the world). The trade to GDP ratio is a common index of the importance of trade for an individual country or for the world as a whole.

Figure 1.1 Growth of world trade, 1870–2010

The sharp rise in the significance of trade since 1950 or so is clearly illustrated in Figure 1.1. In that year the trade to GDP ratio was approximately 8.6%. By 1980 the trade to GDP ratio had reached 16.1%, and it climbed further, peaking at just under 28% in 2008. Figure 1.1 illustrates what has become known as the “first golden age of trade” which occupied the years between 1890 and 1913. This period was marked by a rapid opening of international borders to flows of goods, capital and people, stimulated in part by improvements in transportation technology. This golden age ended abruptly with the onset of the First World War. The decline in trade continued through the interwar years pushed deeper by the Great Depression and increases in tariffs (taxes on the international movement of goods) that became a common policy response to economic decline.

After the Second World War, under the impetus of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), tariffs around the world gradually fell, new transportation technologies such as containerization emerged and new “global” forms of commodity production were rapidly embraced. This period might be regarded as “the second golden age of trade”, though it is more generally referred to as the period of economic globalization, where markets for many different types of goods and services around much of the world economy became increasingly integrated, driven by the emergence of transnational corporations. Much of our attention in this book is devoted to understanding the significance of trade in today’s economy.

History of Trade

Before we further the discussion on trade and globalization, let us first turn our attention to the history of trade. Trade is one of the oldest activities undertaken by humans. Archaeological evidence suggests that long-distance trade occurred well before the modern era. Chinese merchants traveled across Central Asia bringing luxury items such as silk and lacquer ware to Europe in the third millennium BCE. Maritime trade boomed in Southeast Asia as seafarers from the Middle East, India and China engaged in exchanges of cotton (India), sugar (Philippines), tin (Malaysia), spices (Indonesia) and tea and silk (China) destined for Europe (Lockard, 2009). Both the Indian Ocean and South China Sea became hubs of the medieval world’s most important maritime trade networks between the tenth and fifteenth centuries. Indeed, Asia was the center of trade exchanges during this period so much so that it attracted Europeans like the Portuguese to set up forts at Malacca (Malaysia) and Hormus (Iran) to control shipping routes across the Indian Ocean in a bid for a share of the trade activities here.

It was the industrial revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that unleashed historic transformations in Europe and later in North America, and these in turn affected trade permanently. The revolution created durable industrial structures and forms of economic organization for long-distance trade that established the international trade economy that we know today. The modern factory began in eighteenth-century England with the textile revolution and industrial production of cloth. Long a small-scale, cottage industry based largely on wool, cloth production moved into large-scale mills following the introduction of a series of new weaving technologies that rapidly increased the demand for yarn. A switch from wool to stronger cotton fibers fueled the growth of factory production assisted by the British Calico Acts, tariffs on the import of cotton fabrics (largely from India) put in place to protect the domestic British textile industry. In place of cotton fabrics, raw cotton was imported from British colonies, at first India, but then the Americas. As the scale of cotton production expanded, new mechanized spinning and weaving technologies were developed that allowed Britain to establish a position as the world’s most efficient producer of cotton goods. India, once the primary source of imported cotton fabrics to England, now became a major market for British cotton exports.

The growth of the textile sector in Britain stimulated the expansion of related industries. Firms producing industrial machinery developed to support the growth of manufacturing, while many other firms emerged to serve an expanding population of consumers demanding a greater variety of commodities from the rest of the world. All this required imports of raw materials: for example, copper from California, used to make electrical wires. Agricultural trade also became more important. Drinking tea in Britain became a fashionable social activity and most of that tea was imported from South Asia, along with sugar from the Philippines and South America. In other words, trade was central to industrial revolution in the UK, linking this economy to the geographical division of labor that was unfolding in order to support international trade.

As the industrial revolution spread to other parts of Europe, demand for agricultural and raw materials expanded. Unable to compete with England for India’s cotton and other raw materials from the country’s colonies, European countries began to search elsewhere. The era of colonialism is often associated with Europe’s search for raw materials to fuel its factories and industrial growth. It is also associated with the rise of an international economy. By this, we mean that trade in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries facilitated more durable linkages and interconnectedness between countries, and that contact strengthened economic relations. Having previously supplied cotton and sugar to Europe, the United States soon joined the industrial revolution. Major American industrial barons like John Rockefeller formed alliances with railroad and freight companies to develop a transportation system that would facilitate the export of oil, first from Pennsylvania to the rest of the country, and then to the rest of the world, building one of the country’s largest vertically integrated companies, Standard Oil (ExxonMobil today). In so doing, he helped transform the Northeast of the United States into an industrial powerhouse and trade center, served by an extensive network of transportation that ensured the uninterrupted shipment and export of commodities around the world.

Historians associate the spread of colonial trade during the industrial revolution to the change in technology from the invention of the steam engine that allowed ships and trains to ferry cargo across great distances, to the telegraph and telephone that enhanced information flows among trading houses. Such inventions signal a trend of technological progress that trade carried around the globe. Shipping goods great distances was possible because of the cumulative inventions of a number of technicians and scientists in Britain and continental Europe. For instance, Joseph Black’s theory of latent heat inspired James Watt to build a separate condenser that resulted in a more efficient steam engine. Installing the steam engine in ships meant that merchants could sail across the Atlantic Ocean in a week, speeding the movement of cargo. Britain’s precociousness in trade during this period was in part linked to the country’s successful application of new techniques that fuelled the industrial revolution (Mokyr, 2002). This in turn encouraged national and regional specialization that deepened the spatial division of labor between Britain (as producer of capital and consumer goods) and its colonies (as suppliers of raw materials).

Colonial trade was vital to Europe’s industrial modernization. Until then, trade bustled across the Mediterranean Sea, the Indian Ocean and South China Sea so much that the historical geographer Reid (1988) conferred the “Age of commerce” on Southeast Asia in the 300 years prior to the eighteenth century. Trade’s impact then was visible through the growth of cities. As centers of innovation, urban growth was partially explained by the number of port cities that sprang up to support maritime trade. The impacts of trade may be traced by levels of urbanization across Asia. India and China, for instance, had a higher urbanization rate at around 11% compared to levels...