![]()

1

Our Vision of Effective Teaching and Teacher Leadership

Let’s be honest: Teaching looks pretty easy. Teachers are done working by 3 o’clock every day, they have summers off, and some even get snow days! They are in charge. They tell students what to do and then decide how well assignments are done. Teachers have power in the classroom, and they use it. Many of us believe these notions of teaching are true because of our experiences as students. As a result of compulsory education in the United States, we have all watched and listened to teachers for up to eight hours a day, five days a week, thirty-six weeks a year, for thirteen years. Lortie (1975) calls this our “apprenticeship of observation” (p. 67). These in-school experiences lead us to believe we know what teaching is all about—that the years we spend in classrooms make us experts on teaching. This informal apprenticeship can be likened to watching a chef prepare a meal. It looks so simple. All the ingredients are prepared, the appliances are ready, and the oven is preheated. We watch as the chef adds a dash of this and a little extra of that, creating a seemingly perfect plate, both in looks and in flavor. What we don’t see are the complex decisions the chef makes beforehand based on the available fresh, local food. Nor do we understand exactly how the chef determines what subtle touch the dish needs to make it perfect. Even though the chef makes it look easy, when we try to replicate it in our own kitchen, it doesn’t typically turn out with the same exact results. Like cooking, there is more to teaching than meets the eye, and, like the chef, a teacher must make complex decisions on a daily basis.

Still, it seems that when it comes to education, everyone has an opinion, idea, or reform that is intended to fix the reportedly broken system in the United States. The media often portrays teachers as lazy and ineffective or kindhearted but naïve. Certainly, we acknowledge that although there are some teachers who do fit these descriptions, most teachers we know are hardworking, intelligent, thoughtful people who care deeply about their students. Our view seems to be supported by years of national surveys conducted by PDK International/Gallup in which respondents answer a number of questions related to the state of public schools in the United States. One telling indicator involves the United States’ trust in teachers. Nearly three quarters of those surveyed responded that they trusted the men and women who are teaching in public schools. They also rated their own neighborhood schools positively, with 53 percent of respondents giving an A or B rating to their community schools—the highest percentage ever recorded (Bushaw & Lopez, 2013).

In the current educational environment, where scripted curricula are common, students’ standardized test performance is tied directly to teacher evaluation, and change seems the only constant, it is not surprising that many teachers are feeling overwhelmed. Far too often, these feelings are accompanied by claims of powerlessness, silenced voices, and resentment that lead to increasingly negative school and classroom environments. There is little doubt that teachers face challenging circumstances on a daily basis, but we believe that teachers do indeed hold power—power that can be used to influence the external voices of authority attempting to dictate what goes on in day-to-day classroom instruction.

Although out-of-school factors like student health, secure housing, and socioeconomic status, affect student achievement far more than in-school factors (Berliner, 2009), as classroom teachers, we have no control over them. However, when it comes to in-school factors, it is teachers that are most significant (Goldhaber, 2002). Although estimates posit that in-school factors account for approximately 20 percent of variation in student achievement, with teacher quality contributing less than 10 percent of that, one heavily relied upon study found that if a student has a good teacher three years in a row, that student’s achievement scores could be as much as 50 percent higher than a student with ineffective teachers during the same time span (Sanders & Rivers, 1996). Despite the fact that out-of-school factors contribute more significantly to student achievement, we cannot overlook the impact of the teacher, both in the classroom and in the school, since those are factors over which educators can yield some level of influence. Thus, we believe it is important to consider the key characteristics of effective teachers.

What Does Effective Teaching Look Like?

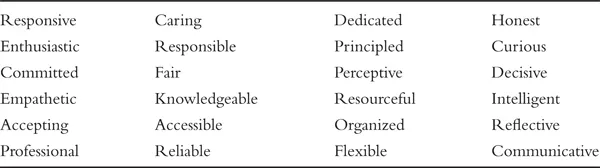

We think everyone agrees that teachers should all possess a certain repertoire of knowledge, skills, and dispositions. Should a fifth-grade teacher understand the difference between a proper and improper fraction? Absolutely. Should a first-grade teacher understand how to teach phonemic awareness through shared writing activities? Most educators would agree that this is important. Take a look at the list of characteristics of effective teachers listed in Figure 1.1. Which knowledge, skills, and dispositions do you think are most important and contribute to effective teaching? Do you already possess many of these? Which might be challenging for you?

FIGURE 1.1 Characteristics of effective teachers (based on: Gabriel, 2005; Stronge, 2007)

Not only are what you teach and how you teach imperative; it is crucial to look at who you are as a teacher as well. We believe “[g]ood teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher” (Palmer, 1998, p. 10); teaching techniques are only as powerful as the teacher presenting them. As we begin our journey to become effective facilitators of student learning, we must first look inside ourselves and examine our own beliefs related to what education means. Teacher enthusiast Parker Palmer theorizes “we teach who we are,” and

… teaching holds a mirror to the soul. If I am willing to look in that mirror and not run from what I see, I have a chance to gain self-knowledge—and knowing myself is as crucial to good teaching as knowing my students and my subject.

(p. 2)

It is just about impossible to disconnect who we are from how we teach. We are shaped by our prior experiences, for better or worse, and these experiences leave an indelible mark on our decision-making processes. By examining experiences and beliefs, we can begin to identify possible biases, assess our own dispositions, and explore how these dispositions can influence student learning. We suggest considering how you apply your knowledge, skills, and dispositions within three broad categories:

- Who are my students?

- What should I teach?

- How should I teach?

Once you begin looking within yourself, you can examine what is occurring around you.

Who Are My Students?

Effective teachers understand where their individual students are coming from, where they are going, and how to get them there. The individual life stories that students enter your classroom with can serve as powerful entry points for instruction. Effective teachers consider students’ prior knowledge and experiences, the language they possess, their interests, and what motivates them as they set instructional goals and carry them out.

The community in which your school is located will likely have a strong impact on how your students perceive themselves. Some students are surrounded by the big city, ride the subway to school each day, and have never seen a live cow or cornstalk. Others may live on a farm, can drive a tractor, and have never seen a building over ten stories tall. When examining your own beliefs, you may realize that you feel students from certain geographic locations are better suited for school or might be more likely to be successful in school. Perhaps you believe a student whose background is most similar to yours will be most successful, or maybe you think just the opposite. It is imperative that you unpack all of your preconceived notions. Instead of focusing on what some students might be ‘lacking’ in their own background, you need to begin to focus on the unique funds of knowledge (Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzáles, 1992): the language (Chapter 7), their interests, and their motivations (Chapter 9) that each child brings to school each day.

The term “funds of knowledge” developed out of the research conducted by Moll and González (1994) to examine the literacy practices of working-class Latina/o children. They define funds of knowledge as:

These historically accumulated and culturally developed bodies of knowledge and skills essential for household or individual functioning and well-being. As households interact within circles of kinship and friendship, children are ‘participant-observers’ of the exchange of goods, services, and symbolic capital which are part of each household’s functioning.

(p. 443)

As children enter school, they bring with them their understandings of the dominant culture of the community and the expected behavioral norms. These forms of capital are sometimes overlooked or undervalued by the dominant school culture when a deficit view is taken. The goal of any effective teacher should be to instruct students in a way that mediates “the schools’ class-based norms and the students’ values, knowledge, and instead of’ (Tozer, 2000, p. 158). Instead of viewing students as an empty vessel to be filled (deficit view), teachers should respect the unique ‘capital’ that each child brings to school, thus, building a reciprocal relationship in which the teacher and student learn from one another without the assumption that one’s prior knowledge and social norms are more important or useful than the other’s. Building this common ground of respect for each child’s background will provide a more equitable learning environment for all students.

What Should I Teach?

Effective teachers also understand how to perform the balancing act between teaching the breadth and depth of the curriculum (Chapter 4) and adapting their teaching based on what their students need (Chapter 5). Think back to when you were a student in elementary school. Do you remember all the textbooks, workbooks, and supplementary materials you and your teacher had at your disposal? If you had effective teachers, they not only understood the goals of the district’s curriculum, but also took into account the needs of their individual students—you! Their instructional goals most likely went beyond the curricular materials located inside your desk or on a bookshelf. Effective teachers constantly engage in a decision-making process to determine what material should be taught, the extent to which it should be taught, and how it can be best conveyed to a variety of learners.

How Should I Teach?

The National Academy of Education (2005) purports that “a teacher has not taught if no one learns” (p. 6). Merely covering all of the standards presented in your curriculum is not effective if your students fail to grasp and retain the material you present. Effective teachers employ instructional frameworks that empower student learning (Chapter 6). These instructional frameworks are even more robust when paired with the differentiation and a variety of instructional groupings and materials (Chapter 5) and teacher responsiveness to individual students’ needs (Chapters 2, 3, and 8).

Some teachers simply think that teaching is all about instruction. This is obviously an important component of effective teaching, but it is not enough. Less effective teachers tend to focus almost exclusively on instruction, whereas more effective teachers realize it’s important to invest in planning and assessment as well. Effective teachers first think about their individual students, what is most important to teach those particular students, and how to provide responsive instruction to the unique group of individuals.

What Makes an Effective Teacher Leader?

We’ve established that although teaching may appear to be a simple task to the observer, it certainly is not. We believe that, at a minimum, teachers must be classroom leaders. Interestingly, although we’ve all had years of experience watching leaders, most people don’t view leadership as an easy task. This belief may explain why the word leadership can be defined in so many ways. The Oxford Dictionary (2014) defines it as, “The action of leading a group of people or an organization,” but a simple Internet search for “definition of leadership” returns literally millions of results. Northouse (2010) defines leadership as, “… a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal” (p. 3), whereas Bennis and Nanus (2003), scholars and pioneers in the contemporary field of leadership studies, define it in a more complex manner, indicating that leadership is a function of knowing yourself, having a vision that is well communicated, building trust among colleagues, and taking effective action to realize your own leadership potential. Even though definitions of leadership like those presented here tend to be associated with politics, sales, and other business-related endeavors, these definitions can quite easily apply to educational leadership. However, educational leadership itself typically refers to leadership by those in administration—curriculum directors, principals, and superintendents—rather than teachers. Despite the fact that few people typically view teachers as leaders, teachers do indeed have a history of leadership.

York-Barr and Duke (2004) indicate that the concept of teacher leadership reco...