![]()

Part I

Policy studies and

qualitative research

![]()

Introduction

Studying senior policymakers and policy in education via qualitative research methods

Pour faire le portrait d’un oiseau/Jacques Prévert

Peindre d’abord une cage

Avec une porte ouverte

Peindre ensuite

Quelque chose de joli

Quelque chose de simple

Quelque chose de beau

Quelque chose d’utile

Pour l’oiseau.

I was conducting an interview with a senior policymaker who runs a conservative think tank in England. The subject of the interview was education policy and reform and its role in promoting equity tools and equality, with regard to legislation. The interviewee, an educated man, presumably in his late thirties or early forties, was criticizing the policy of Prime Minister Tony Blair.

There are good things going on, this government is handing things over to the practitioners. It’s not done through buildings. With the previous government, every part of the building had to be accessible to every person, you have to have wheelchair access to every part of the school without making sure this is cost-effective or practical, this was taking the equality issue to the extreme there was no place for heads [head teachers] to have some common sense. You didn’t get your money for the new school if you didn’t do that. I think people in LAs will adapt, people will not like it, but cutbacks bring rigor, and a need that is more practical and concerned with teaching the kids, and not having a perfect aspect of the building.

Now being a below-knee amputee, who often walks around in shorts, but (fortuitously) not on this cold January London morning, I encountered a dilemma: do I pull up my trouser leg just a bit so the person I am interviewing will get a glimpse of the shining titanium pole, and rethink his comment on accessibility to schools? Or do I keep quiet, to allow open and authentic disclosure of the interviewee’s opinions, not offending or embarrassing him. Being a pretty senior respondent, with whom setting up the interview took two months, and eager to see what he had to say I decided to keep my mouth shut regarding my personal problem.

This vignette presents several ethical and methodological concerns. What is the role or perhaps place of the researcher in the interview with senior respondents? How can expectations be conveyed and settled prior to or during the interview? How does the researcher involve himself/herself in the interview, or detach himself/herself from the respondent and the issues discussed? This is not a ‘classic’ ethical dilemma, often described in literature (Miller et al., 2012; Midgley et al., 2012). The dilemma of the researcher who aspires to uncover the deepest opinions of the interviewee, and perhaps even touching the tangy aspects of the study, the ‘hard core’ intriguing data clashes with the understanding that a qualitative researcher is not a reporter working on an exposé, and should refrain from the dramatic, and the tabloid aspects of research. Policy studies often involve issues that are of public, not just scholarly, interest, and the researcher might be tempted to pursue the spectacular.

This book, however, focuses on the exclusive situation of the researcher studying senior figures in education policy. Several years of experience and numerous encounters have brought me to understand that this specific niche deserves explicit attention.

Prévert’s poem provides delicate metaphors for ethical and methodological dilemmas of a qualitative policy study. He suggests that to catch the bird one has to paint an attractive cage, and paint something beautiful in it, to lure the bird inside. It is delicate because Prévert offers to paint a cage, not to put the bird in a real cage. He explains that the bird may come quickly or you might have to wait for it – but that the time you wait does not result in the quality of the painting. This is an important point for studying policymakers. I have chased one interviewee for four years and eventually had a lovely interview with him. I have chased another interviewee twice over five years, received his agreement only to be canceled finally. Policymakers are busy and sometimes hold sensitive high profile posts, and have access to sensitive information, often shunning exposure. Research, especially qualitative research, reminds policymakers of journalistic interviews. Contrary to completing a questionnaire in a quantitative study, the interview or observation discloses personal focused information on one person and his or her post and responsibilities. This can be interesting, even flattering, to the policymaker, but also intimidating. Having conducted 150 interviews over 14 years with some of the most senior policymakers in England’s education system, this book tells something of the experience and the methodology of this type of study. Some of the issues are: How does the researcher present his/her background, profile, world view? What is the unique quality of doing research on policy, approaching high-powered influential institutions and figures and involving them in your study? How does the researcher balance between the eagerness to contact an interviewee, sometimes after months of futile attempts, and the interviewee’s well-being and safety? Are senior policymakers, with their knowledge, power, and education, exempt from ethical concerns once they agree to take part in a study? Are they immune from the study’s collateral effects? Richard Elmore (2011) from Harvard has edited a recent publication titled ‘I Used to Think and Now I Think’. Drawing upon Elmore’s reflective theme, I used to think that doing research among the most senior figures in a political or organizational system is ethically the easiest. Altogether, senior respondents are supposedly equipped with high awareness of issues of privacy and disclosure. They know something (perhaps more than the researcher) on the possible shortcomings for them or for their organization, and are therefore invulnerable to the possible negative outcomes of revealing in an interview their thoughts or the data they own. The researcher is ostensibly not in a dominant position. Is that truly the situation? The power is still in the hands of the researcher. The interviewee is a person, often eager to present his/her views on the issues at hand, tell about his/her work, achievements, and hardships, perhaps being lured into telling more than he/she had planned, only because, as Prévert writes, of the beautiful painting of the tree and the cage painted with an open door. Sometimes it is not only the researcher who has waited for a long time, but the interviewees themselves who have a grudge against their place of employment, or are looking for an opportunity to express themselves on a contentious issue that resides in the heart of public debate. Is it legitimate to overlook this in order to receive data?

The second vignette is from another interview with a senior government policymaker, in charge of an important department in a large organization, with thousands of academic and professional employees. This interviewee made it clear, at the end of a frank, open, lengthy, and intriguing interview, that he would like to see, and approve, the quotes from the interview, before publication. One year later, as promised, I sent the quotes, which comprised a few hundred words, for approval. I received an email questioning the whole idea of quoting from the interview. First, he said, the quotes do not highlight the essence of his thoughts or the true role of the agency as he saw it. Second, his views were a year old and therefore dated. The correspondence that followed, all via email and with a 2000-mile distance between us, was fascinating and gave me much room for thought on doing this type of research.

As in the previous vignette, several questions arose. To whom does the information ‘belong’ after it has been conveyed to the researcher? How assertive or argumentative can the researcher be with the respondent? How can the researcher protect the respondent’s past opinion, if the mood in the studied organization had meanwhile swung elsewhere, the management had changed, or the policy had been redesigned? Should the researcher be sensitive to such situations, and perhaps alert the interviewee to the dangers of disclosure, even when they openly declare their disregard for any privacy issues? Does the participant’s senior position allow the researcher to be less vigilant on consent and privacy? Does a study cohort, comprised of senior policymakers, necessitate, tolerate, or yield, a unique strategy of the researcher in comparison with other cohorts of participants? The exchange of opinion with the participant in this second vignette caught me a bit off balance; my understanding of the promise I had made at the time of the interview was that it was to warrant that I quoted the exact things said, not to re-write the interview in accordance with the Zeitgeist at the time of publication. I expected senior policymakers, who characteristically hold several academic degrees and are familiar with academic writing and research procedures, to understand that a 90,000-word monograph is not a newspaper article that represents the organization’s situation accurately on the morning of publication, but presents an arc of information, along a period of time. I was also a bit surprised to realize that despite the pleasant interview we had, the respondent did not automatically trust me to safeguard his interests, his privacy, and to represent his concerns with integrity. Reflection pointed inwards by the researcher is needed, and the questions raise serious issues for a researcher to think about. The codes of ethics do not necessarily cover these questions and I intend to address them in this book. Jacques Prévert’s poem continues:

Quand l’oiseau arrive

S’il arrive

Observer le plus profond silence

Attendre que l’oiseau entre dans la cage

Et quand il est entré

Fermer doucement la porte avec le pinceau

Puis

Effacer un à un les barreaux

Et ayant soin de ne toucher aucune des plumes del’oiseau

Faire ensuite le portrait de l’arbre

En choisissant la plus belle de ses branches pour l’oiseau

Peindre aussi le vert feuillage et la fraîcheur du vent

La poussière du soleil

Et le bruit des bêtes de l’herbe dans la chaleur de l’été

Et puis attendre que l’oiseau se décide à chanter

Doing field research, among any population, presents an immanent conflict between the indwelling ethical-intellectual position, and the stance of someone who has a career in research, who wants to publish and disclose new things to the world, and perhaps merely to fulfil plain human curiosity. Furthermore there is a conflict between gaining trust by declaring objectivity or even sympathy, and critical theory. Supposedly senior policymakers are aware of the streams of thought in social research. But are they? Critical theory cautions that research is also about power, colonialism, and dominance (Cannella and Lincoln, 2011).

This book is written to equip emerging and experienced researchers with practical tools to study public policy, and education policy, among senior respondents, and to design a study within the upper tiers of government and civil society (e.g., NGOs, quangos, and ALBs). There is vast literature on qualitative research in general (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011; O’Reilly, 2011), on studying public policy (Moran et al., 2006), on education policy research (Fuhrman et al., 2007; Sykes et al., 2009), on planning and doing qualitative research (Daymon and Holloway, 2010; Maykut and Morehouse, 1994; Morehouse, 2012; Savin-Baden and Major, 2012), on qualitative data analysis (Bernard and Ryan, 2010; Bryant and Charmaz, 2007; Charmaz, 2006; Smith et al., 2009), and on ethics in qualitative studies (Miller et al., 2012). Notwithstanding, this book is a theoretical and practical guide for doing qualitative research on education policy and public policy, as explained above, and focuses on three main issues. The first of which is doing qualitative research on education policy, with the focus on large scale studies; the second issue is the methodology of studying senior participants and analyzing data; the third issue is that of ethics of policy studies and exploring senior participants.

The style of the book is of a hands-on manual with many ‘live’ examples from studies and from personal experiences being provided. Conflicts that riddle qualitative policy studies are explored in detail. The use of interviews versus observations, and combining them; validating qualitative policy studies; conceptual, intellectual, and disciplinary conflicts between the researcher, the participants, and the data; treating methods of analysis as paradigms or a toolbox; are but a few examples.

The conceptual framework of the book

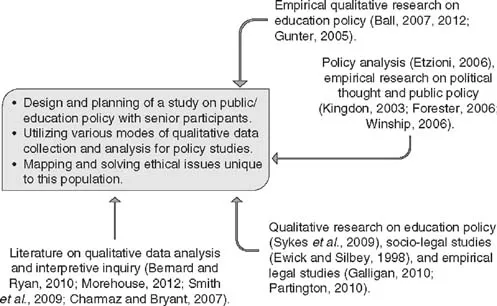

The conceptual framework of the book includes theory that lays the foundations for mapping a field (Bourdieu, 1987; Woods, 2000), for conducting a study in education policy, locating and targeting organizations and individuals for the study, and for identifying the major conceptual themes for the study. Further on, literature on policy analysis (Etzioni, 2006; Forester, 2006; Kingdon, 2003; Winship, 2006), some relating to quantitative work, will be adapted to qualitative research. This will draw upon literature on applicable fields that have already harnessed qualitative research to policy (e.g., sociolegal studies) and of course literature on qualitative research and qualitative data analysis (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011; Bryant and Charmaz, 2007; Bernard and Ryan, 2010).

The following figure presents the literature on which the conceptual framework is based.

Policy studies adopt a linear approach that presupposes a world with separately controlled denominators (Winship, 2006). Qualitative research, in contrast, with its main divisions (interpretative – Moran, 2002; Smith et al., 2009, constructivist and grounded theory – Charmaz, 2006, – the latter both a sub-stream and an analysis method – Corbin and Strauss, 2008), subsumes a multi-layered, complex narrative-based interdependent world in which:

The logical extension of the constructivist approach means learning how, when, and to what extent the studied experience is embedded in larger and, often, hidden positions, networks, situations, and relationships. Subsequently . . . hierarchies of power, communications and opportunity that maintain and perpetuate such differences and distinctions. A constructivist approach means being alert to conditions under which such difference . . . arise.

(Charmaz, 2006: 130–1)

Figure 1.1 The conceptual framework of the book.

Policy analysis draws upon a multidisciplinary assortment of theory. This includes philosophy (Floden, 2007), economics (Levacic, 2008), organizational and political theory (Kingdon, 2003; Manzer, 2003), institutional theory (McDonnell, 2009), social theory (Lauen and Tyson, 2009), and critical theory (Ball, 1994; Dryzek, 2006; ...