The marine industry is an essential link in the international trade, with ocean-going vessels representing the most efficient, and often the only method of transporting large volumes of basic commodities and finished products. ‘Bulk shipping’ is most often defined as the transportation of homogenous bulk cargoes by bulk vessels on an irregular scheduled line, as discussed in Veenstra (1999).

1.1.1 Dry bulk cargoes and vessels

Dry bulk shipping deals with the transportation of dry bulk cargoes, generally categorized as either major bulks or minor bulks. Major bulk cargoes constitute the vast majority of dry bulk cargoes by weight, and includes, among other things, iron ore, coal and grain. Minor bulk cargoes include products such as agricultural products, mineral cargoes (including metal concentrates), cement, forest products and steel products.

In 2012 the seaborne trade volume of major bulk cargoes reached 2,661 million tons, comprising 66 per cent of all seaborne trade of dry bulk cargoes, according to the database of Clarkson Research Studies (2012). Among all the dry bulk trade, approximately 1,110 million tons of iron ore was traded worldwide, about 27 per cent of the total, with the main importers being China, Japan and the European Union. The main producers and exporters of iron ore are Australia, Brazil and India. Second, the seaborne trade volume of coal in 2012 was 1,047 million tons, accounting for about 26 per cent of the total. An increase in the seaborne transportation of coking coal has been primarily driven by an increase in the steel production. Currently, major importers of coking coal are Asia, particularly Japan, India, China and South Korea, but also Western Europe. Australia provides a significant amount of coking coal to Asia, while South Africa, the United States and Canada are major sources for Western Europe. Furthermore, in the global market for steam coal, Japan, China, South Korea and India are major importers. The major exporters include Indonesia, Australia, South Africa, Russia and Columbia. Third, the seaborne trade volume of grain in 2012 was 368 million tons, accounting for 9 per cent of the total. Grain production is dominated by the United States. Argentina is the second largest producer followed by Canada and Australia. In terms of imports, Asia ranks first, followed by the Middle East, Africa and Latin America.

Apart from main bulk cargoes, the seaborne trade volume of minor bulk cargoes was 1,397 million tons, comprising 34 per cent of all the seaborne dry bulk trade, based on figures from Clarkson Research Studies (2012).

1.1.1.1 Dry bulk vessels

There are various ways to define bulk carriers. For example, the Inter-national Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea defines a bulk carrier as ‘a ship constructed with a single deck, top side tanks and hopper side tanks in cargo spaces and intended to primarily carry dry cargo in bulk; an ore carrier; or a combination carrier’. However, most classification societies use a broader definition in which a bulker is any ship that carries dry unpackaged goods.

At the end of 2012, dry bulk carriers represent 40.1 per cent of the world fleet in terms of tonnage and 10.4 per cent in terms of the number of vessels. The world’s dry bulk fleet includes 8,901 ships with a total capacity of 615.5 million tons. Due to economies of scale, dry bulk carriers have become much larger and more specialized.

In terms of deadweight, the worldwide dry bulk carrier fleet subdivides into four vessel size categories, which are based on the cargo-carrying capacity. The first class size is Capesize vessels. The traditional definition of a Capesize bulk carrier, in terms of deadweight, is over 80,000 dwt. However, the sector is changing. Because there have been a number of new super-Panamaxes ordered, which are 82,000 dwt to 85,000 dwt and are able to transit the Panama Canal with a full cargo, a more modern definition of a Capesize would be one based on vessels over 100,000 dwt. The Capesize sector focuses on longhaul iron ore and coal trade routes. Due to the size of Capesize vessels, there are only a comparatively small number of ports around the world with the infrastructure to accommodate them.

The second class size is Panamax vessels. Panamax vessels between 60,000 dwt and 100,000 dwt are defined as those with the maximum beam (width) of 32.2 metres permitted to transit the Panama Canal, carry coal, grain, iron ore and, to a lesser extent, minor bulks.

The third class size is Handymax vessels, which are between 30,000 dwt and 60,000 dwt. The Handymax sector operates in a large number of geographically dispersed global trades, carrying mainly grains and minor bulks. Vessels less than 60,000 dwt are built with onboard cranes that enable them to load and discharge cargo in countries and ports with limited infrastructure.

The smallest class size is Handysize vessels up to 30,000 dwt, which carry exclusively minor bulk cargoes. Historically, the Handysize dry bulk carrier sector was seen as the most versatile. Increasingly, however, this has become more of a regional type of trading. The vessels are well suited for small ports with length and draft restrictions and those that lack decent infrastructure.

The supply of dry bulk carriers is affected by vessel deliveries and the loss of existing vessels through scrapping or other circumstances requiring removal. It is not only a result of the number of ships in service, but also the operating efficiency of the worldwide fleet. For example, port congestion can absorb the additional tonnage and therefore can tighten the underlying supply/demand balance.

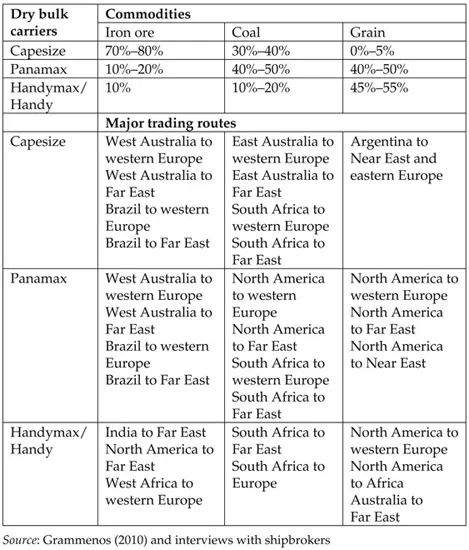

Three types of main cargo and major trading route that dry bulk vessels serve are listed in Table 1.1. (Some information in this table is acquired through interviews with shipbrokers and the remainder is from Grammenos (2010).)

1.1.2 Dry bulk markets

Basically, there are three general types of shipping market, as suggested by Veenstra (1999):

- freight markets

- ship markets

- maritime service markets.

The first type contains markets in which freight or charter contracts are traded; the second contains markets in which ships are traded and the third includes markets in which maritime services, such as finance, insurance and management are traded. Because the first two types of market are relatively uniform in an economic sense and the third one is not, maritime service markets are not the focus of this book, while charter markets and ship markets are.

In freight markets, a subdivision can be made based on different types of contract, including the spot market, the period market and the future/forward market. In light of the substantially increasing influence of the freight forward agreement on the spot freight market, the freight forward market is incorporated into the analysis of the freight market, while freight options, freight futures, etc. are not. Each submarket can also be divided by different types of vessel, such as Capesize, Panamax and Handymax.

Table 1.1 Different types of bulk carrier with main cargoes and major trading routes

In the ship markets, a subdivision can also be made by different ship transaction parties, namely the newbuilding market, the second-hand market and the scrapping market. A further division can also be seen in each submarkets by different types of vessel, such as Capesize, Panamax and Handymax vessels.

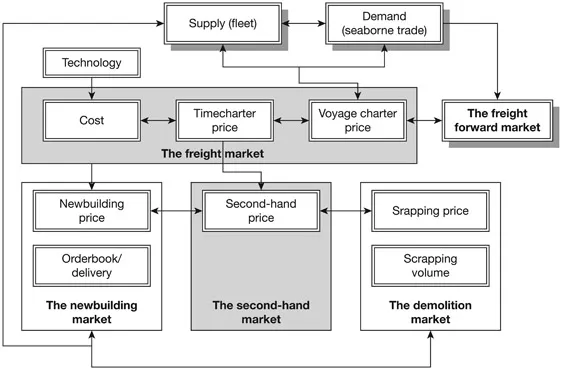

Consequently, economic features of maritime variables in major markets in each ship size are extensively discussed in the book, including the freight market, the freight forward market, the newbuilding market, the secondhand market and the scrapping market. Because the same companies are trading in these four or five shipping markets, their activities are closely interrelated through economic relations. The relations between these markets are thought of influence in one market on the development of another, which can be illustrated as in Figure 1.1.

As can be seen, first, a lead-lag relationship exists between the freight market and the freight derivatives market. Because prices in the freight derivatives market imply the expectation of market players about future movements in the spot market, changes in returns and volatilities in the forward market will spill over into the freight market and will influence market sentiment and activities, causing a subsequent increase or decrease of spot prices. The freight rates and freight derivatives rates are basically determined by market fundamentals, but a distinct difference can be found between these two markets.

Figure 1.1 Economic relations between markets in the dry bulk shipping industry

Second, there are significant influences from the freight market on the ship markets. The ups and downs of timecharter rates in the freight market are the primary mechanism driving activities of market investors. When the freight market is in an upward trend, the effect will be transmitted into the newbuilding market and shipowners will start ordering new ships, while a continuously downward trend in the freight market will possibly cause delay in delivery of new ships or order cancellations.

Changes of timecharter rates in the freight market also influence the prices of second-hand ships, due to changes in expected earnings. Furthermore, old or obsolete ships will be scrapped in an extremely weak freight market, especially during a recession. The newbuilding market and the demolition market together form changes in the supply of the freight market.

Finally, the three ship markets are linked through economic relationships. High prices in the second-hand market will attract shipowners to order new ships, while a full orderbook in the newbuilding market will drive up second-hand prices.

Decisions to scrap ships are also affected by second-hand ship values. If the scrapping value is higher than the second-hand value, old ships will be scrapped. Furthermore, the newbuilding price or the second-hand price can be determined through a net present value relation, as the sum of the expected future earnings, the expected scrapped price and a risk premium, if any.

Each of these central markets can also be divided into segments categorized by ship type: Capesize, Panamax, Handymax and Handy. Dynamics in each market differ with each ship type. Although dry bulk vessels are nowadays standardized vessels, different quality of ships measured by major technical indicators, such as deadweight, main dimensions, speed and the fuel consumption, still has a significant impact on the earnings potential during ship operation. The different quality of a ship can be evaluated by the economic performance of a ship.