eBook - ePub

Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media

Images of World War II in the Japanese Media

- 552 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media

Images of World War II in the Japanese Media

About this book

This unique window on history employs hundreds of images and written records from Japanese periodicals during World War II to trace the nation's transformation from a colorful, cosmopolitan empire in 1937 to a bleak "total war" society facing imminent destruction in 1945. The author draws upon his extensive collection of Japanese wartime publications to reconstruct the government-controlled media's narrative of the war's goals and progress - thus providing a close-up look at how the war was shown to Japanese on the home front. Many of these visual and written sources are rare in Japan and were previously unavailable in the West. Strikingly, the narrative remains consistent and convincing from victory to retreat, and even as defeat looms large. Earhart's nuanced reading of Japan's wartime media depicts a nation waging war against the world and a government terrorizing its own people. At once informed, scholarly, and readily accessible, this lavishly illustrated volume offers an accurate representation of the official Japanese narrative of the war in contemporary terms. The images are fresh and compelling, revealing a forgotten world by turns familiar and alien, beautiful and stark, poignant and terrifying.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Certain Victory: Images of World War II in the Japanese Media by David C. Earhart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Development Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1. EMPEROR SHŌWA

Emperor Shōwa (usually referred to in the West by his princely name, Hirohito [1901–1989]) combined in his person the aura of a head of state, commander-in-chief, and a living god (that is, a manifest deity, arahitogarmi). The degree to which the emperor himself directed and controlled the government, the military, and religious faith was shrouded in secrecy and remains a source of controversy.1 His authority in all matters was, however, beyond question. By the time his photograph first appeared in PWR, three generations of Japanese had been taught to revere the emperor. The Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors (1882) and the Imperial Rescript on Education (1890), documents inspired by simplified Confucian ethics, emphasized obedience to the authority of the emperor and his “proxies” in the military and the government.

The chrysanthemum seal of the imperial house adorning each sword and rifle carried into battle was a constant reminder that soldiers and sailors were agents of imperial will. When troops captured a fort, a city, or an island, they posed for the inevitable “banzai” photograph and gave the obligatory cheer of “Long Live His Majesty the Emperor!” (Tennō heika banzai!) And the press regularly reported that these were the final words of those who died in battle. When a man gave his life in the service, he became a warrior-god (gunshin) and a nation-protecting deity (gokokushin) enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo alongside the spirits of the imperial ancestors. This practice was inaugurated by Emperor Meiji in 1869 when he founded Yasukuni Shrine in the newly renamed capital, Tokyo.

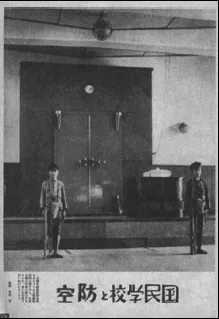

1. PWR 184, 3 September 1941, p. 17. “Citizens” Schools and Air Defense.” The accompanying text says, “We patrol guards do our utmost to protect the vault containing the August Image (goshin’ei). Someday, we will become fine national defense warriors. A heavy sense of responsibility swells our breast.” The chrysanthemum seal is directly above the vault doors.

The official portraits of the emperor and empress were usually kept in a small storehouse (hōanden) in the schoolyard, built specifically to house them. In the event of fire or earthquake, the teacher or person responsible on that day had to transport them to safety, even at the risk of his or her own life. The loss or destruction of the imperial portrait could result in dire consequences.2 Photograph: Nakafuji Oshie.

In Japan, as in China, there was no custom of the emperor’s profile serving as a symbol of the nation or the government. In Europe, from the time of the Romans down to the present day, monarchs adorn currency, but the Japanese did not adopt this custom. Indeed, money was considered vulgar and defiling, and the god-emperor himself never handled it. The chrysanthemum seal on currency, postage stamps, savings bonds and other governmental instruments, on the bow of imperial warships, and above the entranceway to government buildings was emblematic of the emperor. The emperor’s person was synonymous with Japan, but his face was not. Consequently, although the entire war was fought in the emperor’s name, and every military and civilian sacrifice was ostensibly made for him, photographs of the emperor in the wartime press were few. Only thirty-three of 375 issues of PWR (about one of every eleven issues) contained an image of the emperor. The one hundredth issue of PWR contained a breakdown of coverage in the magazine up to that time (24 January 1940); only one percent of the magazine’s coverage was devoted to the emperor and the imperial family.5

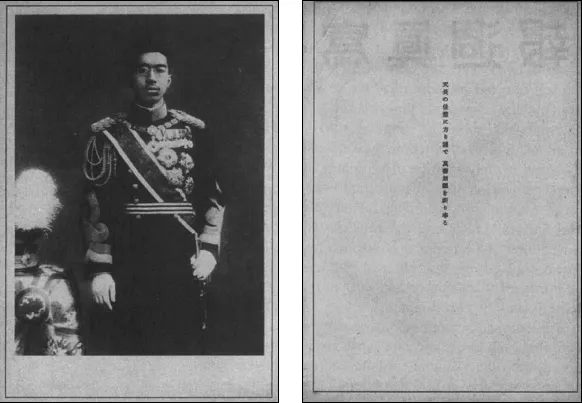

2 and 3. PWR 11, 27 April 1938, inside front cover and p. 1.

The first photograph of the emperor to appear in PWR was the formal portrait of him enshrined in government offices and schools throughout the empire at the time of his enthronement in 1928. It appeared in PWR a few days before 29 April, a holiday honoring his birthday.3 The uniform he wears is that of the sovereign, largely unchanged since the time of his grandfather, Meiji, and patterned after the mid-nineteenth century military-inspired imperial dress then in fashion in Europe. The stiff portraiture also owes much to customs established in Meiji’s day. The caption was something of a command: Offer prayers for myriad and unlimited blessings received through the benevolence of His Majesty.4

The page facing the emperor, the inside front cover (in later issues, numbered page 2), was left blank so that it would act as a tissue-guard protecting the imperial image. PWR usually left the opposing page blank whenever it contained a single-page photograph of a member of the imperial family. The magazine’s title on the cover has bled through this blank page, but has not affected the emperor’s photograph. This portrait was reprinted for New Year’s 1939, along with the official portrait of the empress, in PWR 46, 4 January 1939, pp. 2–3. The photographer is unknown.

The thirty-five different photographs of the emperor within the approximately nine thousand pages of PWR provide examples of the official presentation of his image to the people. He appeared four times in 1938 and six times in 1939 (one of these being a repeat of the “official portrait” [figure 1]). During the same two years, Hitler appeared more frequently in PWR. In 1940, the emperor appeared seventeen times. Seven photographs of him were included in PWR 145, the special double issue commemorating the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of the nation, which centered on the imperial dynasty and its mythology. (Of these seven, four were repeat images from earlier in the year.) Photographs of the emperor were scaled back to three in 1941. The following year, there were six photographs, the same number as in 1939. But in the final three years of the Great East Asia War, his resplendent form was only pictured in PWR one time each year.

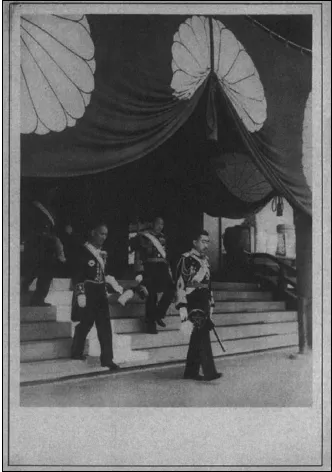

4. PWR 12, 4 May 1938, p. 1. “His Majesty the Emperor was pleased to attend the second day of the Grand Festival at Yasukuni Shrine on 26 April. His Majesty deeply prayed before the spirits of the 4,533 newly enshrined nation-protecting deities and ancestor deities.”

His uniform here is that of the official portrait: sash and cordons, elaborate ribbed sleeves, shoes and pants, and doffed shako with pentacle mark. This is the only contemporaneous photograph of him in this attire to appear in PWR. At this time, the all-out war in China (the “China Incident”) was ten months old and had not yet been declared a “long-term war” by Japan’s military leadership.

For the remainder of the war, the emperor would always appear in what was evidently the field uniform of the commander-in-chief, which came in two colors, khaki for the army (with boots, jodhpurs, and brimmed military cap), and white for the navy.

The chrysanthemum seal on the raised curtain denotes the imperial patronage of the shrine, which was founded by decree of Emperor Meiji in 1869. The photograph is uncredited.

In the pages of PWR, no individual photographer was ever credited with capturing the imperial visage. Many of the photographs of the emperor are not credited at all, even to an agency or ministry. (Of course, PWR often did not credit photographs.) For those that are credited, the Cabinet Information Bureau (publisher of PWR) and the Imperial Household Ministry (in the postwar period, the Imperial Household Agency) were named as photographers. Photographs of the emperor on board navy ships are credited to the Navy Ministry.

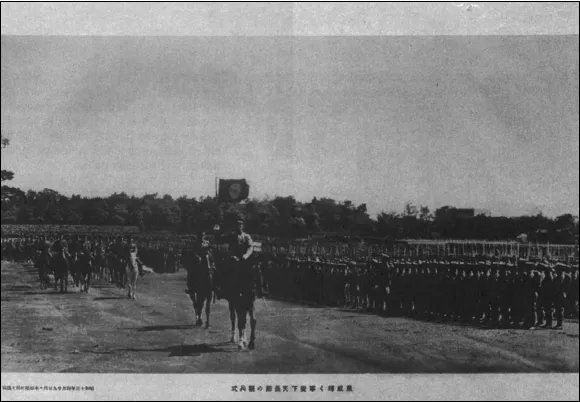

All thirty-five of the photographs of the emperor appearing in PWR (with the exception of the official portrait, figure 1) show him performing some aspect of his official duties as head of state, commander-in-chief, or high priest of State Shinto. Of course, these roles were not strictly segregated, a fact borne out by the emperor’s dress: in all PWR images of the emperor from mid-May 1938 until the end of the war, he appears in the uniform of commander-in-chief, even when visiting shrines. He donned the white naval commander-in-chief uniform for naval inspections. Nearly half of these thirty-five photographs—seventeen images—are devoted to the emperor’s duties as commander-in-chief. Nine feature the emperor on horseback at outdoor military reviews, of which seven were taken at Yoyogi Field, most from an almost identical distance and vantage point. (Photographs like these had appeared in the press before the Manchurian Incident and the creation of PWR.) Two picture him conducting naval reviews, one aboard the battleship Nagato and the other aboard the destroyer Hie. One shows him saluting a graduating class of military students in the palace plaza, while another shows him saluting graduates of the Imperial Army Air Force. Two show him receiving congratulations from the people after important victories. The two most compelling photographs of the commander-in-chief show him reviewing captured war booty in 1942 and presiding over the Imperial High Command in 1943.

5. PWR 13, 11 May 1938, pp. 10–11. “Imperial authority shines at Emperor’s Birthday Dress Review of Troops during the [China] Incident.” The venue is identified as Yoyogi Field, 29 April 1938, the photographer is not. This is the first of nine photographs of the emperor p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Map of the Japanese Empire and the Pacific Theater of World War II

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: A Picture Worth a Thousand Arguments

- 1. Emperor Shōwa

- 2. The Great Japanese Empire

- 3. Men of the Imperial Forces

- 4. A People United in Serving the Nation

- 5. Warrior Wives

- 6. Junior Citizens

- 7. “Now the Enemy Is America and Britain!”

- 8. The Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere

- 9. Uchiteshi Yamamu: “Keep Up the Fight”!

- 10. Faces of the Enemy

- 11. Dying Honorably, from Attu to Iwo Jima

- 12. The Kamikazefication of the Home Front

- Conclusion: Endgame

- Appendix 1 : Annotated Bibliography of Japanese Wartime News Journals

- Appendix 2: Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index