![]()

Chapter 1 | | University Planning and Architecture 1088–2015: An Evolving Chronology |

1.1 Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio, the seat of the University of Bologna from 1563 to 1803.

University design is a civic art form. This is a lofty claim, yet the following sweep through its rich history from its medieval beginnings to the icon buildings of the present day will serve to demonstrate how social, philosophical and cultural forces have come to mould academic design across the eras. This chapter will chronicle the history of campus architecture as a condensed narrative of the most energetic and innovative phases of university design over the last 900 years. This summary methodology necessarily omits many countries and institutions which have contributed to this story, and focuses primarily on the UK, continental Europe and the US, where many of the most stimulating or influential achievements in this field have originated. Yet even an abridged survey can demonstrate the theme that links university design across its long history: the architecture of higher education is an architecture of ideology. From the colonial colleges of early America which personified in built form the utopian ideals of its settlers, to the modernist set-pieces of post-Second World War institutions, which were informed by a new mood of optimism, democracy and utopianism, universities have consistently explored the expressive capacity of the built environment to symbolise the cultural and institutional zeitgeist.

1.2 The earliest universities were itinerant communities with no fixed premises. Lectures took place in churches, rented rooms, and anywhere else that could be found.

Early Beginnings

The medieval university was largely a European phenomenon, inaugurated by the University of Bologna, allegedly founded in 1088.1 Bologna, together with Paris and Oxford, form the triumvirate of European university prototypes from which all subsequent examples descend. Medieval universities were essentially the products of the twelfth-century Renaissance, the rediscovery of classical learning that flourished in the 1100s. In centres of learning across Europe, renowned masters drew increasing numbers of students around them. Eager to safeguard and promote their mutual interests, they collected into scholastic guilds, akin to those of merchants and artisans. Gradually these guilds were officially sanctioned by popes, prelates and princes, attracting an increasing number of students and thus evolving into the forerunners of the modern university. In Italy, the model of Bologna was copied at Modena, Reggio nell’Emilia, Vicenza, Arezzo, Padua and Naples. Spain saw the founding of great schools at Salamanca, Valladolid, Palencia and Seville. Universities in Cambridge, Coimbra, Prague, Cracow, Vienna, Heidelberg, Cologne, Louvain, Leipzeig, St Andrews, and others ensued in quick succession (see Appendix, Table 1). Over the course of two centuries, the university had established itself as the prime sponsor of learning within major towns and cities.2

Universities took root in thriving cities supported by prosperous agricultural regions that allowed for relatively inexpensive living costs. They were ingrained within the urban centres and gradually shaped the characters of their host towns. Yet despite this union, the early medieval university had no tangible presence within the city. Lectures took place in houses rented by the masters, while examinations and assemblies were typically held in churches and convents; it possessed no buildings (Figure 1.2). The institutions were, as yet, itinerant communities of masters and students drawn from throughout Europe. The members of Paris’s university, for example, largely originated from outside the Ile-de-France region. As ‘foreigners’ the students and masters bore little fidelity to their host city, and, when scholarly privileges were called into question, they felt no compunction in moving to another centre of learning. University migrations were a common phenomenon, and were frequently the force which stimulated the birth of new universities, as evinced by scholarly migration from Bologna to Vicenza in 1205 and Oxford to Cambridge in 1209. These episodes stimulated some of the first examples of university architecture. Following a major exodus of Bolognese professors to the University of Sienna in 1321, for example, the following year the municipality purposed to bind the university to the city by building a chapel exclusively for scholars; it was the University of Bologna’s first edifice.3

As the Middle Ages progressed, as student populations increased and ceased to migrate, universities began to acquire property. In the fifteenth century, the University of Paris procured lecture halls, colleges, lodgings and churches on the left bank of the Seine, giving the university a distinctive presence in the area that became known as the Latin Quarter. The University of Orléans built its Salle des Thèses from around 1411, the only secular medieval university building to survive in France. In the same century, Salamanca erected a quadrangle to house teaching facilities, Las Escuelas (Figure 1.3). Meanwhile, as the Renaissance gathered pace, the universities of Italy also increasingly felt the desire for the prestige that accompanied having a physical presence of purpose-built academic facilities. By 1530, the scholars of Padua were taught in the university building, and, spurred on by rivalry, Bologna soon followed suit. The University of Bologna obtained permanent quarters in the Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio in the city centre in 1563 (Figure 1.1). Entered through a magnificent portico, and sited around a courtyard, the complex housed seven lecture halls for law, six for arts and medicine, and two large halls. Today, over 6,000 heraldic shields, immortalising the university’s professors and students, and an incredible array of art work throughout the staircases, halls, teaching rooms and arches offer a glimpse of the rich history this building holds.4

The Palazzo dell’Archiginnasio typified Spanish and Italian universities of the Renaissance in its four-sided courtyard format surrounded by arcaded cloisters plus an impressive main façade. The model was transported to South America when its colonialists founded its first universities, the University of San Carlos in Guatemala (main building circa 1763) being one such example (Figure 1.4).

1.3 Escuelas Menores at the University of Salamanca, dating to the fifteenth century.

1.4 University of San Carlos (c. 1763) in Guatemala reproduced the cloistral, quadrangular typologies of the early European universities.

As the Renaissance progressed, universities old and new acquired befitting academic quarters, comprising lecture theatres, assembly rooms, chapels, libraries and lodgings. These structures, often incredibly lavish, were physical manifestations of the omnipresence of the European university, a visible sign that the university had evolved from a loose association of scholars and masters into an institution. The distinctive architecture and central urban locations of the late medieval and early modern university indicate that its place in the life of the city was firmly established; the university towns became stamped with a personality of their own. The most iconic expressions of this were, undoubtedly, the universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

The two medieval universities of England distinguished themselves from their fellow European institutions through one decisive feature: their adherence to the collegiate system. This not only came to determine approaches to living and learning, but fundamentally shaped the physical evolution of the two institutions. The college first came into being, in fact, in twelfth-century Paris. Students as young as 14 were drawn there from throughout Europe, and so halls or dormitories known as hospita catered for their housing needs. The Collège des Dix-huit, for instance, was founded in 1180 by a wealthy English merchant, Jocius of London, to shelter 18 poor clerics while they attended lectures. Only a small amount of supervision took place in these foundations, usually by a master or cleric, and instruction remained external. A small number of residential colleges existed in Italy, but they failed to achieve the same popularity as in Paris and England, probably because the supervision of scholars was not such a priority. Italian universities, unlike Paris, Oxford and Cambridge, did not enrol very young students. The colleges housed only a fraction of students, and, since Italian communes forbade teaching outside what they deemed the ‘public university’, teaching colleges did not evolve there.5

It was only in England, at Oxford and Cambridge, that academic colleges, comprising a body of scholars living under the teaching and guidance of masters, gathered real momentum. Yet, the colleges were not present from the outset. In both centres, it was at first the norm for students to lodge with townspeople. Quickly, ‘halls’ or ‘hostels’ became popular, in which groups of students lived communally in a rented building presided over by a master. Beam Hall was one such establishment in Oxford; surviving intact in Merton Street, it illustrates their inherently domestic character that made little imprint on the architecture of the town. These transient establishments came and went; some 200 names have been recorded in Oxford. The colleges, however, achieved a permanent presence. With precise stipulations regarding discipline, study and the attendance of religious services, the colleges quickly assumed the residence functions of the halls, and in time took on teaching responsibilities. They differed from the early academic halls in that the colleges received endowments of lands, rents and church revenues, which made them financially secure, and this in turn enabled them to wield the tremendous architectural impact upon the two ancient cities that they still boast today.6

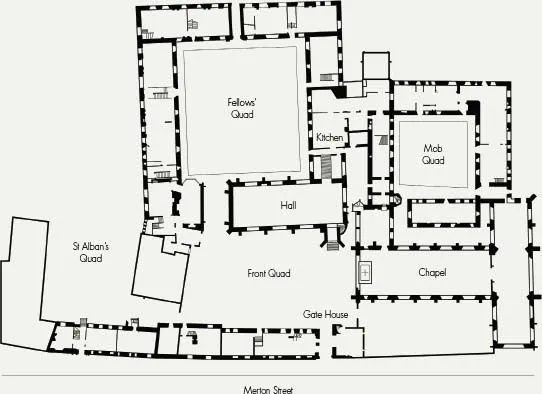

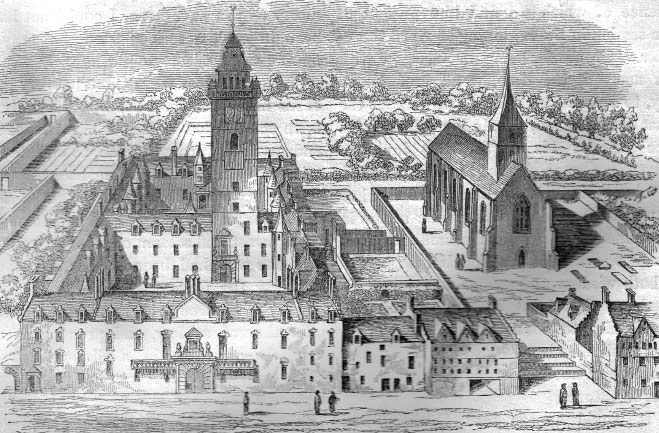

The colleges erected the universities’ first impressive buildings. Their financial independence meant that they could build liberally and lavishly. The first colleges were founded in quick succession in the thirteenth century at Oxford: University College (1249), Balliol (1263) and Merton (1264), which possesses the earliest surviving collegiate buildings. When Merton was founded, no model existed as to the form an Oxford college should take. Its buildings arose in piecemeal fashion from 1266, irregularly placed around a courtyard, reproducing an arrangement found in contemporary bishops’ palaces and some manor houses. The first buildings to be constructed were the dining hall (much rebuilt 1872-4) forming the south side of the quadrangle, the Warden’s house on the opposite side, and a chapel on the third side, where work commenced in 1290. A residential courtyard followed from 1287 with the construction of Mob Quad, sited to the south of the chapel. Consisting of four ranges of roughly equal length and height, this was Oxford’s first regular quadrangle (Figures 1.5, 1.6).7

1.5 Merton College, Oxford, from David Loggan’s Oxonia Illustrata (1675).

1.6 Plan of Merton College, Oxford, built from 1266.

1.7 University of Glasgow as it appeared c. 1650, organised around enclosed quadrangles.

The enclosed quadrangle, first seen at Merton, set an enduring precedent for collegiate architecture at Oxford and Cambridge, and indeed yielded considerable worldwide influence. The medieval universities of Scotland (St Andrews, founded 1413; Glasgow, founded 1451 (Figure 1.7); and Aberdeen, founded 1495) appropriated much the same pattern. Reminiscent of conventual cloisters, the format recalled the tradition of monastic learning that the universities inherited. Indeed, several colleges were actually founded in, or ...