![]() Part I

Part I

Autonomous Nature![]()

1 Greco-Roman Concepts of Nature

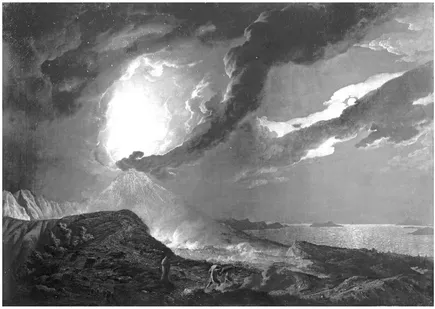

On August 24, 79 C.E. Mount Vesuvius volcano, near Naples, Italy, exploded. “Broad sheets of fire and leaping flames blazed at several points, their bright glare emphasized by the darkness of night.” Black clouds of ash, fumes, and pumice flew miles into the air for two days, raining down on the ancient city of Pompeii and burying it in debris. Pliny the Younger who at the age of eighteen survived the eruption wrote of its terror. His uncle Pliny the Elder perished. A few years later, the younger Pliny who had thrown off mounds of ash in his struggle for life summoned the courage to write about his uncle’s experience:

They debated whether to stay indoors or take their chance in the open, for the buildings were now shaking with violent shocks, and seemed to be swaying to and fro as if they were torn from their foundations. Outside, on the other hand, there was the danger of failing pumice stones, even though these were light and porous; . . .

Elsewhere there was daylight by this time, but they were still in darkness, blacker and denser than any ordinary night, which they relieved by lighting torches and various kinds of lamp. My uncle decided to go down to the shore and investigate on the spot the possibility of any escape by sea, but he found the waves still wild and dangerous. A sheet was spread on the ground for him to lie down, and he repeatedly asked for cold water to drink.

Then the flames and smell of sulphur which gave warning of the approaching fire drove the others to take flight and roused him to stand up. He stood leaning on two slaves and then suddenly collapsed, I imagine because the dense, fumes choked his breathing by blocking his windpipe which was constitutionally weak and narrow and often inflamed. When daylight returned on the 26th—two days after the last day he had been seen—his body was found intact and uninjured, still fully clothed and looking more like sleep than death.1

The experience of Pliny the Younger graphically illustrates the way in which peoples of the ancient world lived within autonomous nature. Volcanos, earthquakes, hurricanes, and disease, although not everyday events, loomed as exemplars of the wrath of the gods and of worldly chaos—unpredictable events over which humanity exercised no control.

Figure 1.1 Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples. Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797), ca. 1776–1780. Copyright Tate, London, 2015.

In this chapter, I discuss the Greco-Roman background to the idea of Nature as an active, creating entity versus Nature as the created world—ideas that during the Christian Middle Ages and Renaissance would become the concepts of Natura creans/naturans and Natura creata/naturata. The association of natural disasters with unpredictability and chaos has its roots in ancient philosophy. Especially important to later natural philosophy is the gendering of nature, matter, and chaos as female and Intellect, Ideas, and Form as male. I describe Plato’s idea of the Demiurge as an intelligent craftsman who creates the visible world and compare it with the craftsman in the Hippocratic corpus who attempts to extract secrets from the body of nature and the human being. I also discuss Aristotle’s merging of the creating and created within each individual object in the natural world and Lucretius’s concept of Natura Creatrix as a creating deity. Both Lucretius and Plotinus portrayed Nature as lawful and orderly, but sometimes rebellious and disorderly, hence unpredictable and uncontrollable. These ideas would be elaborated in ensuing centuries as Christianity drew on and integrated Greek and Roman ideas with those of the Bible and in the concepts of experimentation and mathematization as ways of predicting and controlling autonomous nature developed during the Scientific Revolution.

Chaos

In his Theogony (ca. 700 B.C.E.), Hesiod depicts Chaos (Khaos, the gap) as the gaping void, or primordial condition out of which everything emerged. Chaos, as female progenitor of the gods, was the chasm or open gap that gave birth to the gods and the cosmos. Next came Gaia, the female earth, and Eros, or sexual desire.

Verily at the first Chaos came to be, but next wide-bosomed Earth [Gaia], the ever-sure foundations of all the deathless ones who hold the peaks of snowy Olympus, and dim Tartarus in the depth of the wide-pathed Earth, and Eros (Love), fairest among the deathless gods, who unnerves the limbs and overcomes the mind and wise counsels of all gods and all men within them.2

For Hesiod, the Sky or Heaven (Ouranos; Uranus) was male and the Earth (Gaia) was female, a gendered division that was to play a central role in the history of science and the environment. “And Heaven came, bringing on night and longing for love, and he lay about Earth spreading himself full upon her.”3 The personifications of a male Sky and female Earth, along with Chaos (female and mother of the gods) as the gap between them, set the stage for later efforts to understand and control a chaotic, unpredictable world often depicted in female terms.

In attempting to understand the origins of nature, its laws and activities, and how to predict what a chaotic Nature might do next, Greek and Roman philosophers devised a number of theoretical frameworks. Nature in these systems was sometimes lawful, sometimes unruly, and sometimes simply the everyday world resulting from nature’s creativity. Many of the significant terms were gendered male or female and associated with ideas of order/disorder; form/matter; intellect/receptacle; being/becoming; lawful/unruly, and so on.

Early Greek Ideas of Nature

The foundational questions for Greek (and other) philosophers were:

- Of what is the world composed and how does change occur? The Ontological Question.

- How do we know? The Epistemological Question.

- How should we act? The Ethical Question.

The ontological question involves nature as a creating principle (natura creans/naturans) and nature as created world (natura creata/naturata). The created world is composed of entities such as ideas or matter (or particles of matter); change occurs through processes such as those brought about by a creator, a god or gods, a demiurge, by emanation from the original One, or as the ceaseless activity of atoms or corpuscles. The epistemological question involves knowing, e.g., (for Plato) through recollecting what was lost to the individual mind after birth, by comparing the world of appearances to the pure forms, through ideas such as mathematics or the Good, or (for Aristotle) by observation through the senses. The ethical question involves the choices that humans make in leading the good life and how those choices can be justified.

These questions set up major problems for Greeks, Romans, early Christians and beyond. Especially important were dichotomies and dialectics that existed between the concepts of order/disorder; stability/chaos; lawful/unruly; permanence/change; perpetuity/turmoil; creation/annihilation; good/evil. How did nature as an active, creative force come into conflict with nature as an unchanging, lawful order? What early ideas on the formation of the created world existed and how and when did the problem of nature as unruly and rebellious arise?

The ideas of nature and law emerged early in Western history. The terms Phusis (Physis), nature, and Nomos, law, presented a dichotomy containing embedded gendered meanings with women often being associated with physis (feminine) and men with nomos (masculine). Here the contradictions between nature as an active force and nature as a lawful order begin to arise.4

Two fundamental contradictions identified by early Greek thinkers laid the foundations for nature as both unchanging and changing, predictable and unpredictable, ordered and chaotic. The first idea of permanence and stability was expounded by Parmenides of Elea (fl. ca. 500 B.C.E.), the second idea—the lack of permanence and the continuance of change—was elaborated by Heraclitus of Ephesus (ca. 535–475 B.C.E.).5

Parmenides flourished in Elea on the coast of southern Italy around 500 B.C.E. Using a series of logical noncontradictory statements, he argued that Being exists and change cannot exist. By its very definition, Being is and Not-Being is not. Existence exists and nonexistence does not exist. Moreover, Being is eternal. It has always existed and has no beginning or end. Change does not exist and is, in fact, impossible. Why? Because Being cannot come from Not-Being, because Not-Being by definition does not exist. Logically, A (i.e., Being, a thing) cannot arise from not-A (i.e., Not-Being, no-thing). Nor can Being be destroyed, because by definition it cannot go into nonexistence to become Not-Being. Nor can Being arise from something, because if Being came from Being, how would it differ from its parent? It cannot vanish, for to do so it would become Not-Being, but Not-Being by definition does not exist.

Thus Being is, has always been, and always will be. There is no time; no past, present, or future. Being is one, continuous and without parts. For how could the parts of Being be distinguished from each other? One part could be distinguished from another only if some Not-Being existed beside it (as if cut into pieces by a biscuit cutter). But Not-Being does not exist (and therefore cannot act as a biscuit cutter). We define a thing by what it is not. But we cannot define Being by what it is not because Not-Being does not exist. Being is therefore without parts and continuous throughout. It is One. The unifying first principle of philosophy, therefore, is the One. The One would be interpreted by Plato as the unchanging pure Form, by Christianity as God, and by the mechanistic philosophy of the Scientific Revolution as God’s unchanging laws of nature.

Around the same time, i.e., 500 B.C.E. Heraclitus of Ephesus deposited at the temple of Artemis his untitled book containing all his knowledge. Among its maxims are: “Nature loves to hide”—Nature hides “her” secrets from humans. And, “You cannot step twice into the same river for fresh waters are ever flowing in upon you,”—Everything is in constant flux and ever changing. From these phrases emerge many of the complex, contrasting meanings associated with nature as an unpredictable, ever-changing, chaotic force versus nature as a predictable, lawful order.6

Heraclitus’s phrase “nature loves to hide” implies that nature’s secrets are hidden from human knowledge and must be discovered. Artemis, at whose temple Heraclitus deposited his book of knowledge, like her Egyptian counterpart Isis, personified a Nature who harbored secrets to be revealed, unveiled, and extracted in the search for insight and understanding. Extracting those secrets, or truths, from an active, creative nature (natura naturans) would allow not only for knowledge of the natural world (natura naturata), but also for the possibility of its control and management. Mathematical analysis of pure forms and logic was one approach; experimentation and technology (techne or art) the other. Plato’s divine Craftsman exemplifies the first approach, Hippocrates’ earthly Craftsman the second.

Plato's Demiurge as Divine Craftsman

Plato’s (424/3–348/7 B.C.E.) account of the creation of nature comes from the Timae...