![]()

1 The miracle of the West

Scholars discussed in this chapter believe the West rose mostly because of inherent qualities of its culture. In general, those who emphasize internal factors – as opposed to external ones, like climate, geography, or interactions with other peoples – tend to emphasize cultural values and beliefs, in particular those stemming from the Christian religion, which for centuries formed the core of Europe’s value system. Even historians who give the most explanatory weight to institutions or technology in answering the “how” question, typically resort to cultural underpinnings when trying to address the “why” question.

Christian Europe: uniquely dynamic (Christopher Dawson)

In a series of writings beginning in 1922 and culminating with his Religion and the Rise of Western Culture (1950), Christopher Dawson traced the rise of the West to medieval Europe when, in his interpretation, the “barbarian” cult of heroism and ideal of aggression fused with the Christian cult of saintliness and ideal of self-renunciation. The elements of this dualism struggled for mastery not merely within society but within people’s heart and conscience, creating conditions of extraordinary dynamism, constant soul-searching and self-criticism, and ultimately world-changing innovation. The West rose, according to Dawson, for distinctive cultural reasons.

Christopher Dawson (1889–1970) spent his early years in Hay Castle, Wales, his mother’s ancestral home, an ancient ruin dating to the twelfth century. He later recalled: “What I felt most at Hay was the feeling of an antiquity – the immense age of everything, and in the house, the continuity of the present with the remote past.”1 When he was seven, his family moved to his father’s estate in Yorkshire. The family prayed together every morning, and both father and mother taught the precocious child a variety of subjects, both spiritual and secular. After a miserable experience at two private schools on account of poor health and athletic inability, Dawson had more success with a private tutor before entering Oxford University in 1908. He fell head over heels in love with a Catholic girl in 1909, converted to Catholicism in 1914, and married her two years later. After brief stints in the law before, and in military intelligence, during World War I, he settled into a life of independent research, freelance writing, and occasional university teaching.2

Extremely learned in both the classics and religious subjects but also in sociology, history, and economics, Dawson early on vowed to devote his life to understanding and explaining how cultures flourish and deteriorate. Using an interdisciplinary and cross-cultural approach, he found in each society’s religious life the key to understanding its successes and failings, its rising and declining. As he wrote in 1950, “the great world religions are, as it were, great rivers of sacred tradition which flow down through the ages and through changing historical landscapes which they irrigate and fertilize.”3

He conceived of human history as unfolding in stages across Eurasia over several thousand years beginning with the emergence from 4500 to 2700 BC of isolated river-valley civilizations – in Egypt, Mesopotamia, northern India, and northern China. These societies came to be dominated by priestly castes, centralized economies, and theocratic god-kings. In the next age, from 2700 to 1100 BC, intercultural diffusion and mutual influencing flourished across Afro-Eurasia, as dozens of new societies emerged along the margins of the core areas of civilization. The great classical cultures and most of the world religions appeared next – the third age – from the Athenian city-states and the Roman Empire in the west to the Gupta Empire and Imperial China in the east. In the fourth age, according to Dawson, great cultures flourished across Eurasia – medieval Christendom, Byzantium, the Islamic civilization, and Tang and Song China. Devastating invasions in the 1200s-1400s, however, stunted the development of China, Persia, India, and the Near East, leaving only Western Europe unscathed.4

What distinguished Europe from other major cultures, according to Dawson, and made it capable of uninterrupted innovation and development for nearly ten centuries, was an inherent dynamism and tendency to almost continual reform. The essential ingredient in Europe’s dynamic culture was an unremittingly missionary form of Christianity. This missionary movement originated in the first century after Christ in Hellenistic cities of the Near East and continued for hundreds of years as apostles and preachers spread the faith further and deeper into Western Europe. After the fall of Rome, scores of charismatic spiritual leaders – like St. Patrick in Ireland and Gregory the Great in England – laid the foundations of medieval European culture. As the intellectual life of the continent fell into decline in the sixth century, the movement reversed itself, with scholars and missionaries from Ireland and England reinvigorating cultural life among the Germanic and Frankish peoples. For the first time in the evolution of human culture, according to Dawson, there emerged in Europe a distinctive form of societal dualism in which political and cultural elites wielded power and influence in separate but complementary and relatively balanced spheres. In all the other great cultures, including Byzantium, one leader and one set of elites dominated both politics and culture. Europe’s organic “separation of powers” made it possible for innovators in many walks of life – first in the spiritual realm but gradually also in commerce, urban development, and intellectual pursuits – to transform and to create European traditions and institutions through “a spontaneous process of free communication.”5 Dawson goes on:

It is only in Western Europe that the whole pattern of the culture is to be found in a continuous succession and alternation of free spiritual movements; so that every century of Western history shows a change in the balance of cultural elements, and the appearance of some new spiritual force which creates new ideas and institutions and produces a further movement of social change.6

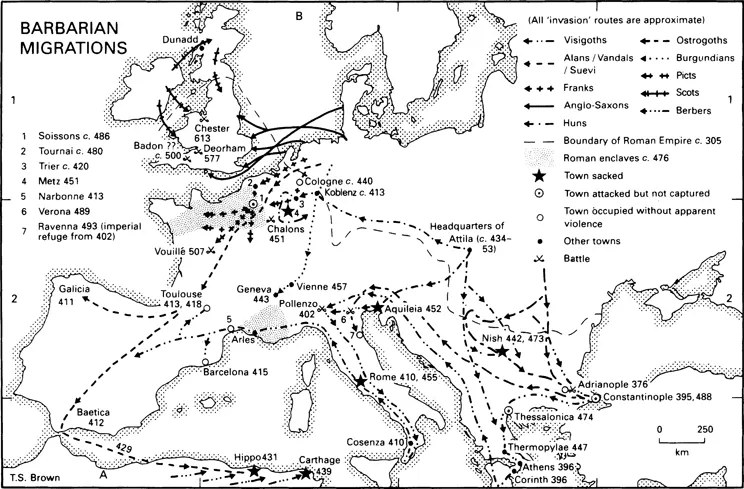

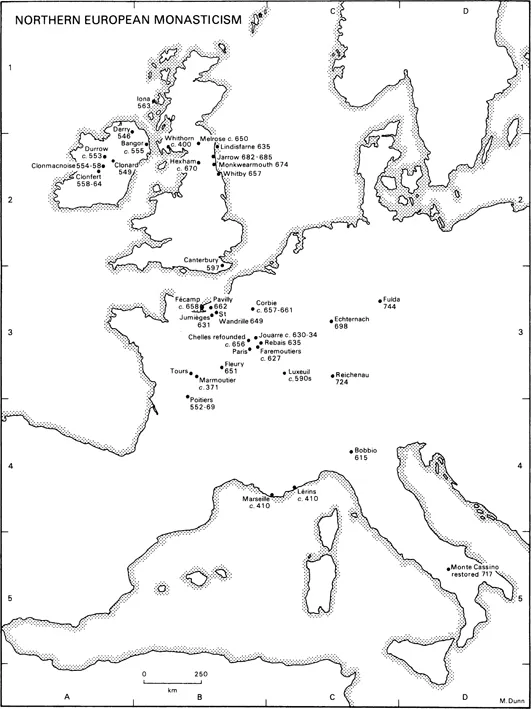

Europe’s tendency to innovation and reform was fostered not only by ruling elites and institutions in competition but also by competing ideals and outlooks – the “cult of heroism and of aggression” of the mostly Frankish tribes that dominated Western Europe after the fall of Rome and the sophisticated theological culture and the ideals of nonviolence, asceticism, and self-denial of the Christian Church and successive generations of religious reformers. Yet these apparently incompatible visions gradually fused into a single, transformative cultural mix (see Map 1.1 and Map 1.2). For example, the Anglo-Saxon warrior-king, Alfred the Great (849–899), translated into Old English the hugely influential late-Roman Consolatio Philosophiae by the Christian thinker and saint, Boethius (ca. 480-ca. 524).

It was precisely the high culture and Christianity infused from the Mediterranean and Near Eastern lands by spiritual leaders like Sts. Paul and Augustine and Boethius and Pope Gregory the Great (r. 590–604) that created from the largely undeveloped European interior a unified and vibrant Christendom. This new culture combined the refinement and discipline of the classical world with the raw energy of the “barbarian” cultures but also a radically different view of values and authority. According to Dawson, “a new principle had been introduced to the static civilization of the Roman world that contained infinite possibilities of change.”7 He quotes the popular reaction to St. Paul’s preaching at Thessaloniki. He and other Christians “have turned the world upside down … and [they] are all acting contrary to the decrees of Caesar, saying there is another king – Jesus” (Acts, 17:6–7). Never before in history had a rapidly spreading faith justified placing one’s primary allegiance in a transcendent deity and relegating earthly authorities to a secondary status. Within a few centuries, moreover, the Roman Church had replaced the Roman Empire as both spiritual and at times even temporal leader of Western Europe.

Yet the key element in the Christian faith that conquered pagan Europe was not the subtle theology of the Church Fathers but the reputedly awe-inspiring supernatural powers of saints and martyrs. For centuries after the fall of Rome, much of Western Europe fell into deep material poverty, extreme lawlessness, fierce exploitation, and barbaric warlordism. The Church offered not “civilization” but a promise of divine judgment and salvation from the horrific depths of earthly depravity into which the world had sunk. The heart and soul of the Christian cultural and intellectual life in those centuries was the celebration at mass of the redemption of mankind by the Incarnation of the Divine Word. The mass told a sacred history of human creation and salvation, of the divine purpose on earth and in eternity. In the dramatically rich and beautiful liturgy – full of music and poetry – the people found meaning to life in ways far surpassing the nature myths of the Eleusinian and other ancient mysteries.8 In such a dark age, one can imagine the fervor with which both rich and poor sought solace within the only stable and continent-wide institution of Western Europe – the Church.

Map 1.1 Barbarian migrations: Invasion by successive waves of warlike migrants imparted to Europe a “cult of heroism and of aggression.”

Map 1.2 Early European monasteries: Monasticism infused sophisticated theological culture and ideals of nonviolence, asceticism, and self-denial throughout Europe.

A web of monasteries and monastic orders – often under the nominal authority of the papacy but de facto independent of local prelates – preserved classical culture and spread the Christian faith across Europe. Western monasticism, while deeply influenced by Eastern practices emphasizing asceticism and withdrawal from society, was far more oriented toward building community and developing social order in an environment woefully lacking them. Monastic communities became microcosms of social and economic life where the brothers and sisters followed strictly articulated rules, sharing everything in common, diligently providing for their own upkeep regardless of social status and origin, ministering to the neighboring populations, but above all devoting themselves to the life of the spirit, praying up to eight hours a day for the salvation of the world.

Europe’s elites – even many men and women of royal blood – eagerly joined the communities, which to some extent replicated the society of warriors from which they came. One swore absolute obedience to an abbot just as to a chieftain and pledged self-sacrifice and devotion to sanctity instead of to honor and bravery. Both lifestyles aimed at extreme heroism – the willingness to forfeit one’s life for a cause. In practice the monastic life involved many arts and sciences necessary to high culture, like reading, writing, calligraphy, music, and – especially important – a proper understanding of the flow of time in order to faithfully observe the complex daily, weekly, and yearly religious offices. Monastic houses in the most far-flung places became centers of learning, teaching, social cohesion, and economic development. Hundreds of able disciples of charismatic abbots gradually established similar institutions in distant lands, implanting the seeds of a new, dynamic culture all across Western Europe. Many of the great monasteries actually served as urban centers north of the Alps until cit...