![]()

Section 1

What is spatial reasoning and why should we care?

SECTION COORDINATOR: YUKARI OKAMOTO

Chapter 1: What is spatial reasoning?

Spatial reasoning has always been a vital capacity for human action and thought, but has not always been identified or supported in schooling. In recent years we have noticed its role in maneuvering through and managing one’s world much more. We survey its history and the recent recognition of its growing importance – within mathematics, across other disciplines, and in life beyond the school.

Chapter 2: The development of spatial reasoning in young children

Drawing primarily from the psychological literature, this chapter describes what we currently know about young children’s development of spatial reasoning. We provide an overview of spatial reasoning as a multifaceted construct through concrete examples. This chapter provides a context for the chapters to follow.

Chapter 3: Developing spatial thinking

Once believed to be a fixed trait, there is now widespread evidence that spatial reasoning is malleable and can be improved in people of all ages. In this chapter, we first discuss the relationship between spatial reasoning and mathematics and then present a variety of spatial training approaches shown effective in not only supporting children’s spatial reasoning but mathematics performance as well.

![]()

1

WALTER WHITELEY, NATHALIE SINCLAIR, BRENT DAVIS

In brief…

Spatial reasoning has always been a vital capacity for human action and thought, but has not always been identified or supported in schooling. In recent years we have noticed its role in maneuvering through and managing one’s world much more. We survey its history and the recent recognition of its growing importance – within mathematics, across other disciplines, and in life beyond the school.

Emerging emphases on spatiality

In recent years, large-scale and highly influential organizations, such as the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (2010) and the National Research Council (2006), have advocated for a more “spatial” approach to the teaching and learning of K–12 curricula.

This push to emphasize spatial reasoning signifies a shift in educational values and long-term educational objectives. These transitions are most frequently associated with the growing need for expertise in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics – the STEM disciplines. An important element in increasing STEM participation and success, it is widely asserted (e.g., Newcombe, 2010; Uttal et al., 2013), is to increase the education and development of spatial thinking.

The suggestion is not unwarranted. Extensive research has shown that spatial reasoning ability and success in STEM domains are strongly correlated (e.g., Wai, Lubinski, & Benbow, 2009). High school students who demonstrate strong spatial skills are more likely to enjoy, enter, and succeed in STEM disiciplines. Well-honed spatial skills are also associated with innovation by practitioners within these fields (Kell et al., 2013). The relation between spatial thinking and mathematics is pronounced; people with strong spatial skills are generally successful at mathematics (Wai et al., 2009; Mix & Cheng, 2012). These findings suggest that developing spatial thinking skills may support interest and achievement in STEM.1

Our particular focus in this book is on the development of spatial reasoning in early years (birth to Grade 3) mathematics, but it is important to note that spatial reasoning plays a vital role across all grades and within most, if not all, academic subjects. In this opening chapter, we situate the early years focus within the K–16 experience. This chapter also serves to frame our broad, collective intention to survey the available literature – historical and contemporary, academic and professional – with an eye toward providing a broad-based-but-useful introduction to the array of perspectives, the multiple fields of research, the spectrum of interpretations, and range of practices and children’s activities that are collected under the banner of spatial reasoning.

For us, this project demands close and sustained attention to both historical circumstances and emergent situations. Paying attention to the past helps us to understand how varied constructs of spatial reasoning have contributed to (or have not contributed to) current conceptions of mathematics as a network of mathematical science disciplines and popular enactments of school mathematics. Paying attention to the present compels us to be mindful of what it means to be educated in a rapidly changing world. And so, while we aim to speak to the realities of entrenched school mathematics, we also look toward a model of school mathematics that is fitted to emergent personal, social, cultural, and ecological circumstances.

Our spatial reasoning project

This book is a tightly integrated discussion, not an edited collection of papers. While principal authorship for each chapter has been attributed to specific individuals (based on weight of contribution), every member of our Spatial Reasoning Study Group took part in structuring, critiquing, and integrating every chapter.

That detail is of particular relevance because our project is deliberately transdisciplinary. Our group comprises individuals with expertise in psychology, mathematics and mathematics education. Given that diversity of specialization, one of our first shared realizations when we began to discuss the research on spatial reasoning was that core constructs are often treated in radically different ways across domains, in spite of highly similar vocabularies. (See Chapter 9.) This point is particularly obvious around diverse meanings, varied methodologies and key examples associated with the phrase “spatial reasoning.”

For example, there is considerable debate on the relationships among “visualization,” “visual-spatial reasoning,” and “spatial reasoning.” Some commentators use these terms interchangeably; others offer subtle distinctions; some argue they must not be conflated. Another topic that is engaged in various ways is the role of language in the development of spatial reasoning abilities, with extremes of opinion being, at one pole, they are inextricably intertwined and, at the other, spatial reasoning can develop relatively independently from language.

We do not aim to resolve these debates. On the contrary – and as undertaken mainly in Chapters 2 and 3 and returned to in Chapter 9 – a main strategy in the book is to preserve differences in perspective in order to bring them into productive conversation. That is, our focus is not an unambiguous definition, but a working knowledge that will support richer understandings of how children engage with/ in their worlds. That said, our project is to contribute to a more nuanced discussion of the phenomenon of spatial reasoning. We thus embrace work that tightly links spatiality to the visual – as exemplified, for example, in Tahta’s (1989) work. He proposed the following three “powers” involved in working with space:

• imagining, which involves seeing what is said;

• construing, which involves seeing what is drawn or saying what is seen; and

• figuring, which involves drawing what is seen.

While Tahta did not use the phrase “spatial reasoning,” for us his three powers illumine the developmental interplay of practices, highlighting in particular the movement in reasoning to and from language. These practices provide a powerful basis on which to organize a curriculum and a useful starting point for articulating our own working understanding of spatial reasoning.

Through our varied and collected experiences within mathematics and learning spatial reasoning, we have extended Tahta’s and others’ lists to include a range of dynamic processes that we see as characterizing spatial reasoning – and that can, but do not necessarily, involve concurrent work with language. Our preliminary list of verbs follows:

• locating

• orienting

• decomposing/recomposing

• shifting dimensions

• balancing

• diagramming

• symmetrizing

• navigating

• transforming

• comparing

• scaling

• sensing

• visualizing.

We are attempting to be suggestive here, not exhaustive. To that end, we revisit this list – critiquing, extending, and re-organizing it – in the closing chapter.

We see both theoretical and practical value in the exercise of identifying and organizing such aspects. On the level of theory, these verbs compel us to be clearer on what we imagine ourselves to be discussing. And in the realm of practice, for example, one way for classroom teachers to assess whether a lesson is tapping into spatial reasoning is to determine whether some of these dynamic processes are being targeted or called into action.

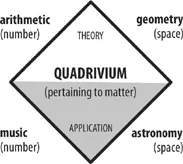

In somewhat different terms, this book is founded on the assumption that spatial reasoning is not an isolatable competence, nor one that can be parsed into discrete sub-skills. Rather, it is an ever-evolving potential that arises within the complex interplay of many aspects. This lens on spatial reasoning and the spatial dimensions of knowing reminds us that what it means to “do mathematics” cannot be dissociated from everything else that humans study and do – a point that we regard as a resurgence of a waning sensibility. For example, until the beginning of the 20th century, people who practiced mathematics also typically engaged in science. In particular, spatial reasoning figured prominently in thinking about physical properties and laws: Euclid wrote a book on Optics; Pythagoras and Archimedes worked in a world in which geometric reasoning was more trusted than arithmetic. Studies in the medieval university were organized in large part around the Quadrivium, comprising disciplines that are both number-focused (i.e., Arithmetic and Music) and space-focused (i.e., geometry and astronomy – see Figure 1.1). The applied spatial domain of Astronomy was of particular relevance, foundational as it was to the work of traders and others needing to locate, navigate, and survey (see Henderson & Taimina, 2005, “Introduction”). As recently as a century ago, it was common for such prominent mathematicians as Hilbert, Poincaré and Noether to be simultaneously occupied with the physical and applied sciences, especially Physics and Engineering. In other words, the dissociation of spatial reasoning from the practices of mathematics, both in formal educational settings and in popular conception, is recent.

Figure 1.1: The Quadrivium – which, along with the mind-focused Trivium of Logic, Grammar, and Rhetoric – constituted the core of study in the medieval university.

This point might be illustrated by looking at the treatment of geometry in school mathematics. As detailed in Chapter 4, a principal motivation for the first government-funded public schools was to fill needs for workers with particular skills created by industrialization, urbanization, and capitalism. A consequent priority in public schools of the era was basic numeracy, which was tethered to a diminished status of geometry in formal schooling. Much in contrast to mathematical study of earlier centuries, in which the sciences and geometry were obvious and rich locations for spatial reasoning, the mathematics of the Industrial-era school was stripped down to the bones of useful arithmetic and formulaic algebra. Not only was most geometric content removed, the elements of arithmetic and algebra that remained were formatted with minimal demands for visualization and spatial reasoning. That trend was actually amplified in the mid-20th century, when school mathematics saw an even further erosion of topics in geometry (Whiteley, 1999). Combined, such happenings have contributed immensely to the lacuna in opportunities to engage in spatial reasoning in the context of school mathematics.

On this point, it is not without irony that school mathematics, as experienced by most citizens of the modern world, has come to be mainly about “figuring things out.” That expression traces back to the 15th century, originally having to do with “picturing in ...