eBook - ePub

Corrections

Exploring Crime, Punishment, and Justice in America

- 660 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Corrections

Exploring Crime, Punishment, and Justice in America

About this book

Corrections: Exploring Crime, Punishment, and Justice in America provides a thorough introduction to the topic of corrections in America. In addition to providing complete coverage of the history and structure of corrections, it offers a balanced account of the issues facing the field so that readers can arrive at informed opinions regarding the process and current state of corrections in America. The 3e introduces new content and fully updated information on America's correctional system in a lively, colorful, readable textbook. Both instructors and students benefit from the inclusion of pedagogical tools and visual elements that help clarify the material.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Understanding Corrections: Where Are We?

Chapter Objectives

- Recognize that prison is a growth industry.

- Distinguish between punitive and rehabilitative ideals in corrections.

- Recognize and discuss the impact of the “war on drugs” on corrections.

- Understand and identify the restorative justice trend in corrections.

- Identify and discuss the justifications for sanctioning.

Key Terms

- Community justice

- Deterrence

- Frills

- Incapacitation

- Indeterminate sentences

- Lex talionis

- New penology

- Public safety

- Recidivism

- Rehabilitation

- Rehabilitative ideal

- Reintegration

- Restorative justice

- Retribution

- “Scared Straight”

- War on drugs

Introduction

When most people hear the term “corrections,” they probably think of prisons, striped uniforms, cell blocks, armed guards, and surly prisoners. Part of American corrections is prisons, but corrections is much more than that. Corrections includes prisons, jails, halfway houses, group homes, probation, parole, intensive supervision, electronic monitoring, restitution programs, victim–offender mediation, and even the death penalty. Corrections can be defined as all that society does to and with offenders after they have been found guilty of a crime. Corrections even includes some things done to offenders prior to conviction, such as detention in jails pending adjudication of guilt and programs for offenders who are diverted out of the criminal justice system.

This book examines and explores American corrections. We will look at all that corrections encompasses. We will try to help you understand what is happening in American corrections and why corrections is taking some of the directions it is taking. For example, American corrections appears to be continuing to emphasize punishment over treatment. We will attempt to examine trends such as the emphasis on punishment, explain where such trends originated, and discuss their consequences. To begin this process, we will take a brief look at some recent trends in corrections. Then we will discuss correctional goals and the themes of the book.

The Current State of American Corrections: Present Trends

Growth

One of the clearest trends in corrections is growth. Corrections is currently a major growth industry in our country. All aspects of corrections are growing. At year-end 2009, 7.23 million adults were under some type of correctional supervision in the United States. The majority of these offenders (70%) are supervised in the community either by probation or by parole. More than 1.5 million adults are incarcerated in prisons, while another approximately 760,000 are in local jails. This is a substantial increase from previous decades, roughly double the total correctional population that was witnessed in the mid–late 1980s. However, the corrections population growth seems to be slowing down. In fact, 2009 figures reflect a 0.7% decline in correctional populations, the first decline since 1980 (Glaze, 2010).

The recent growth in corrections populations has caused concern for many states. The Pew Center reported that in 2008 more than 1 in every 100 adults was incarcerated in a U.S. jail or prison. Of even more concern is that this figure is even higher for men ages 20 to 34 (1 in 30 is in confinement) and even higher still for black men ages 20 to 34 (1 in 9 is in prison or jail) (Warren, 2008). This trend is beginning to reverse itself. In 2008, more than half of the states witnessed a decrease in imprisonment rates (Sabol et al., 2009).

Explore on the Web

To find numerous reports and information on corrections, go to the National Institute of Corrections (NIC) web site at www.nicic.org or the Bureau of Justice Statistics web site at www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs.

The Punitive Ideal

A second major trend in corrections is a demand for greater punishment of criminals. There is demand for capital punishment, lengthy prison sentences, truth in sentencing (making offenders actually serve most of the time announced in their sentences), “three strikes and you’re out” laws (no parole after three convictions), “no frills” prisons, and little support for probation and parole (Austin & Irwin, 2001)(Figure 1.1).

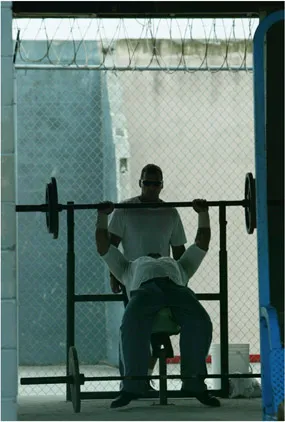

FIGURE 1.1 An inmate lifts weights at the Hendry Correctional Institution in Immokalee, Florida. Physical fitness programs and equipment in prisons have been labeled as “frills” by some who argue that inmates should fare no better than the least advantaged individuals in society. Credit: AP photo/Wilfredo Lee

We will examine this trend by discussing the call for “no frills” prisons. “Frills” in prison can refer to a number of educational, recreational, psychological treatment, or physical fitness programs and equipment. The frills label has been applied to college courses, access to cable television channels, exercise equipment (such as weightlifting equipment, tennis courts, and softball diamonds), and more. One argument against frills is philosophical: the “least eligibility” principle. This argument contends that prisoners should fare no better than the least advantaged individuals in society. Therefore, if disadvantaged or low-income individuals do not have cable television, exercise equipment, and so forth, it is unjustifiable for prisoners to have such amenities. Another argument contends that prisons are meant to be both punitive and deterrent (harsh enough to frighten persons considering committing crime out of actually committing the crime they are considering). Frills detract from both the punitive and deterrent dimensions of prison. Other arguments are that amenities are costly and that some, such as weightlifting equipment, can actually be harmful. Prisoners can use weights to become stronger and then assault other prisoners or guards (or both). The federal prison system has outlawed weightlifting equipment in new federal prisons.

Proponents of “frills” argue that educational, treatment, and recreational programs keep prisoners busy and help them develop life skills. Keeping inmates busy can reduce tension and aggression, thereby preventing problems such as riots or other forms of prison violence. Staff tend to like such “frills” because they help keep prisons safe for prisoners and staff. One response to the “least eligibility” argument is to make societal conditions better for the disadvantaged. In other words, rather than argue that the disadvantaged have no access to college courses or exercise programs, perhaps society has an obligation to provide more for the disadvantaged rather than keeping them in their current underprivileged state. (For more on frills in prisons, see Box 1.1.)

One author calls the emphasis on punishment the “penal harm movement” (Clear, 1994). Part of the reason for this emphasis on punishment is the conservative doctrine of

BOX 1.1 “No Frills” Prisons

Angola State Prison in Louisiana is a prime example of a “no frills” prison. Prisoners receive long sentences and spend much of their time farming the agricultural fields, which are an integral part of the prison complex (it is sort of a 20th-century plantation with prisoners instead of slaves). Prisoners do have a chance to watch television at night. If they work hard enough, they can move from hand labor (hoes, rakes, shovels) to the luxury of operating a tractor.

Eglin Federal Prison Camp, a federal minimum-security prison camp in Florida, is an example of a prison many would say is loaded with frills. Many of the offenders are white-collar criminals. There is no imposing concrete wall or fence around the perimeter of the institution. Instead, there is a painted white line. If an offender crosses it, he is considered an absconder and is subject to transfer to a traditional federal maximum-security prison. Cells are actually dormitory cubicles.

Prisoners work 7 hours a day for a token wage (a paltry per-hour rate). What makes the prison seem soft, however, is the presence of tennis courts, baseball diamonds, and a jogging track. If an observer were to visit Eglin, he or she might confuse it with a college setting. At a minimum, a visitor might confuse the physical fitness facilities at Eglin with similar facilities at a college campus or a physical fitness club.

The comments of Gresham Sykes (1958) put these two prisons in perspective (for a complete discussion of Sykes’s comments, see Chapter 7). Although one has traditional cells with iron bars and the other has dormitory cubicles, and although one forces the men out into the fields and the other may require federal prisoners to groom the adjacent Air Force golf course for 7 hours a day, both facilities share more similarities than differences. Both deprive the inmates of freedom, autonomy, goods and services, heterosexual sex, and security. (Eglin is less secure because of its white-collar crime clientele, but every offender is still a criminal, and riots and disturbances have occurred at minimum-security facilities like it.) In both places, the offender is constantly reminded that he is a number rather than a whole person and that the staff does not really care what he thinks or prefers. He is there to follow orders or else. It is true that a sentence to a prison camp like Eglin is easier to endure than a sentence to Angola, but both places take away freedom and dignity. As allegedly “frilly” as Eglin might appear, travel agents have yet to put it on their list of vacation attractions.

individual responsibility and free choice. Because many persons assume that individuals are free to choose and are responsible for their choices, punishment seems to make sense. Those who commit crimes are seen as deserving of harsh punishments. Harsh punishments are also considered to be a deterrent; they are supposed to scare or intimidate would-be offenders from committing crimes. Punishment advocates also view harsh sentences as incapacitative. Putting offenders in prison removes their capacity or ability to commit crime. If offenders are in prison, they cannot commit new crimes on the street.

The Search for Efficiency, Effectiveness, and Accountability

Still another trend in contemporary corrections is a concern for efficiency, effectiveness, and accountability. In the mid-1930s, there was little or no emphasis on the financial bottom line in corrections. Prisons were considered necessary, and state legislators passed budgets that provided for their funding. Today there is increasing concern about the costs of operating prisons and other correctional enterprises, which is magnified by the growth in correctional populations. That growth means that correctional populations consume an ever-larger portion of state budgets. When prisons became more expensive than state spending on education, prison costs became an issue of intense concern and debate. To give one example of costs, California spent almost $9 billion on corrections in 2007 (Warren, 2008).

One indicator of the emphasis on costs is the privatization movement in corrections. At year-end 2006, 113,791 state and federal prisoners were in privately run facilities. At midyear 2008, 126,249 state and federal prisoners were in privately run facilities. This represents 7.8% of all state and federal prisoners. The federal system had more than 32,000 prisoners in private facilities. Texas had more than 18,700 prisoners in private facilities (West & Sabol, 2009).

Another part of the focus on efficiency and accountability is simply a greater concern for results. Decades ago, both police officials and correctional officials did not have to justify their existence and their budgets. It was assumed that criminals had to be caught and locked up. Now, however, both law enforcement and correctional officials must state their goals and objectives and then demonstrate that they have been successful in achieving the desired results and achieving those results at the lowest possible cost.

Many state policymakers are calling for the adoption of evidence-based practices. The goal of evidence-based practices is to improve the criminal justice system by implementing programs and policies that have been shown empirically to reduce recidivism and to eliminate programs and policies that do not work to reduce recidivism (MacKenzie, 2006; Sherman et al., 2002). Aos and colleagues (2006) conducted a systematic review of 571 studies that assessed the effectiveness of a variety of correctional programs in Washington State. The findings of their study indicate that cognitive-behavioral therapy, drug treatment programs, adult basic education, and early childhood intervention programs are effective strategies for reducing recidivism. However, more research is needed to determine whether juvenile day-reporting programs, juvenile curfews, and domestic violence courts are effective (Aos et al., 2006). Throughout this textbook, we will continue to present the reader with evidence-based research.

The emphasis on efficiency and effectiveness has been labeled the “new penology” (Feeley & Simon, 1992). Whereas corrections used to be concerned with reforming or rehabilitating the offender, the new penology is concerned with managing prison and community corrections populations as efficiently as possible. In an interesting turn of events, what used to be considered failure is now considered success. In the new penology, it does not matter so much that an offender commits a new crime while on community supervision (probation, parole, or some other type of supervision). This used to be considered failure. What matters now is that the correctional workers note the offense and have the offender mo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Online Instructor and Student Resources

- 1 Understanding Corrections: Where Are We?

- 2 The History of American Corrections: Where Did We Come From?

- 3 Corrections and the Courts

- 4 Community Corrections

- 5 Restorative Community Justice

- 6 Jails

- 7 Prisons and Prison Life

- 8 Correctional Administrators and Personnel

- 9 Special Populations in Prison

- 10 Women Offenders and Correctional Workers

- 11 Juvenile Corrections

- 12 The Death Penalty in America

- 13 The Future of Corrections

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Corrections by John T. Whitehead,Kimberly Dodson,Bradley Edwards in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Criminal Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.