![]()

1

W(h)ither the European Shrinking City?

William J. V. Neill and Hans Schlappa

There is a consensus on the key principles of future European urban and territorial development which should: be based on balanced economic growth and territorial organisation of activities, with a polycentric urban structure; build on strong metropolitan regions and other urban areas that can provide good accessibility to services of general economic interest; be characterised by a compact settlement structure with limited urban sprawl; enjoy a high level of environmental protection and quality in and around cities.

(European Commission, 2011: vi)

One of the main ways economies increase worker productivity, and thus grow richer, is through the reallocation of people and resources away from low productivity segments to more efficient ones. In business this means that bad firms go bust and good ones grow to great size. Something similar should hold for cities. Where workers can be put to use at high levels of productivity labour scarcity will lead to fast growing pay packets. Those pay packets will attract workers from other cities. When they migrate and find new, high paying work, the whole economy benefits.

(The Economist, 2015: 20)

While European urban policy confronts different visions of the future as cities struggle to find a niche in the current competitive global economic environment, it has been commented that much of mainstream planning theory is too preoccupied with ‘talk about the talk’, with the underlying assumption that the ‘right kind of talk’ can provide answers to pressing concerns (Yiftachel, 2012: 542). Another planning theorist usefully reminds us that ‘we as planners need to focus attention on our capacities to envisage alternatives and demonstrate the possibilities for a better world’ (Campbell, 2010: 475). This book deals with one policy aspect of a sorely needed more imaginative planning approach to conjuring with spatial imaginations. Specifically, in the face of the phenomenon of shrinkage in many European cities, it asks the basic question: What is to be done to make the situation better?

The approach taken in the contributions presented is essentially pragmatic. Theory abounds on the current unfolding of global urban dynamics but the common perspective that ties the chapters together is the belief that proactive governance, at all spatial scales in the management of shrinkage, is crucial. Implicit is the endorsement of a latticed approach to horizontal and vertical governance within the European Union, albeit open to the interpretation of the advancement of the wider project of integration by a ‘softly, softly’ approach (Morphet, 2014: 167–169). Within this perspective the contributions, from a combination of academics and practitioners, focus on what seems to improve matters in shrinkage contexts and what further possibilities can be explored. The key question pursued is what planning actions could avert or mitigate the worst effects of contraction or indeed seek spatial re-envisioning opportunities that are not so driven by the relentless concept of growth.

At these times of continued and severe budgetary austerity it seems important to work on the development of tools which facilitate the creation of initiatives that are based on the existing capabilities and resources local actors have access to and can control. While this does not remove the need for the development of policy that specifically deals with urban shrinkage at national and European levels, many suggestions put forward here would provide some immediate support for the many European cities caught up in an ongoing spiral of decline. In short, while there can be little doubt that shrinking cities need help to tackle the problems they face, the question is how can they be supported to ‘shrink smart’?

The urban vision endorsed is that there does remain space for better planning in a neoliberal world (Campbell et al., 2014). As opposed to what can be a pessimistic ‘post-political’ academic outlook (Oswald, 2009: 95) lamenting the managerial as opposed to social visionary approach to running many European societies, it is important to acknowledge that good management can make a difference for the better. Before a brief review of authorial content, the introduction proceeds by way of an overview of the extent of shrinkage, debates on causality and the broader European urban policy context represented in particular by the document Cities of Tomorrow: Challenges, Visions, Ways Forward (European Commission, 2011), embedded as it is within the Europe 2020 competitiveness agenda.

Extent and Causality of Shrinkage

Increasing numbers of cities in Europe and elsewhere are losing out in the fight for investment and growth, finding themselves on the sidelines of global shifts in production and consumption. This is the central argument of the recently published OECD report on demographic change and shrinking cities which is based on a wide range of case studies from across the globe (Martinez-Fernandez et al., 2012b). The picture that emerges from this and earlier global studies (UN-HABITAT, 2008) is that large cities will continue to attract financial and social capital which will facilitate their continued growth, while many small and medium-sized cities will begin or continue to decline (Pallgast et al., 2013; Martinez-Fernandez et al., 2012a).

The causes of shrinkage in a European context remain a matter of intense debate with a major study of European shrinking cities reporting ‘multiple, intersecting causations of shrinkage, as well as variegated experiences’. It points to changing drivers of population shrinkage at different spatial scales related to economic decline, demographic change, suburbanisation and political upheaval. While recognising the range of theoretical positions with various lenses to explain shrinkage (stage and life-cycle theories of urban development, uneven development perspectives, for example) the researchers contend that ‘shrinkage should not be universally attributed to a single macro explanation’ with the particular local governance arrangements always having to be borne in mind (Haase et al., 2013: 4–5). In short there is ‘enormous variety of real, existing “shrinkages” across Europe’ (ibid.: 14).

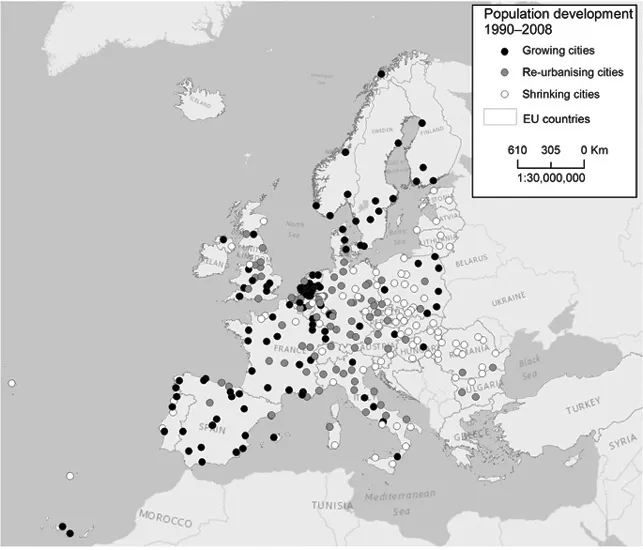

While the debates on the definition of shrinking, declining or stagnating cities are ongoing (Pallgast, 2010; Pallgast et al., 2013; Großmann et al., 2012) there is some consensus that in Europe the proportion of small and medium sized cities caught up in a spiral of socio-economic decline has been on the increase for several decades (Haase et al., 2013; Bontje and Musterd, 2012; Bernt et al., 2012). Using the definition of urban shrinkage developed by the Shrinking Cities International Research Network (SCiRN) and the COST Action Cities Regrowing Smaller (CIRES), Wiechmann and Wolff (2013) show that almost half of Europe’s cities, which are home to one-third of Europe’s population, are shrinking. Their comparative analysis of spatial distributions of growth, stability and decline between 1990 and 2010 comes to the following conclusion:

This overview of shrinking cities in Europe provided … clearly demonstrates that urban shrinkage is an incontrovertible and increasingly important fact as well as a major challenge for future urban policies and urban research in Europe … It proves that shrinking cities can be found in 33 out of 37 countries in Europe and that today a substantial part of cities of all sizes shrink.

(Wiechmann and Wolff, 2013: 16)

Many scholars warn that without targetted action the number of urban settlements where local and regional governments are unable to gain control over socio-economic and physical decline will continue to grow, together with the associated effects of unemployment, social polarisation, exclusion and poverty. Academics working on the CIRES project argue that ‘in Europe we are dealing with islands of growth in a sea of shrinkage’ (Wiechmann, 2012: 40), and suggest that decline rather than growth is the most likely ‘development’ trajectory for many European cities (Bontje and Musterd, 2012; Bernt et al., 2012; Mykhnenko, 2005). In drawing together contemporary research on shrinking cities Großmann et al. conclude:

Shrinkage will not disappear from Europe’s urban picture; on the contrary, given the global demographic change and the local dynamics of the global economy (and of global crisis effects), it is very likely that urban shrinkage will become an even more widespread phenomenon in the near future.

(Großmann et al., 2013: 224, parentheses in original)

Figure 1.1 Population development in large European cities 1990–2008

Source: Kabisch et al., 2012

European Policy Context

Despite a rapidly growing number of studies which show that urban shrinkage is continuous and widespread in Europe, many policymakers and practitioners still consider urban shrinkage as a localised and temporary problem. In an earlier study Wiechmann shows that the administrative systems and strategies in shrinking cities persist in remaining solely growth oriented with decision-makers believing that strengthening economic competitiveness and aiming for demographic growth are the best ways of arresting or reversing the shrinkage process (Wiechmann, 2003). Many scholars argue that such attitudes need to change because a market led recovery of cities in decline cannot be relied upon. They suggest that EU policy needs to provide an explicit focus on the needs of shrinking cities (Bernt et al., 2012; Wiechmann, 2012) and that public agencies must develop their abilities to engage local stakeholders to collaboratively develop viable forward strategies (Martinez-Fernandez et al., 2012a; Haase and Rink, 2012; Hospers, 2012). Here Schlappa and Neill (2013) have recently argued that the rosy goals in both the EU Cities of Tomorrow report and the Europe 20/20 strategy need to be tempered with a less growth driven approach when it comes to shrinking cities. This is a challenge facing the EU directorate general for Regional Policy, now rebranded as the DG for Regional and Urban Policy with a mandate to coordinate the urban initiatives of the Commission as a whole.

Chapter Focus

The structure of the book takes us from broad issues concerned with policy and planning frameworks, governance, participatory planning and the social economy to specific challenges encountered by shrinking cities. These include facilitating interim uses of land and buildings, developing urban green spaces, reducing service infrastructures and the collaborative development of strategy and services. The contributions to this book have been chosen so that a wide range of issues was addressed, including:

- learning from shrinkage experience in the United States

- civic engagement, leadership and community development

- the temporary use of facilities and resources

- addressing problems of oversized utility infrastructures

- environmental design and land-use planning

- opportunities for urban food production

- the management of urban land markets

- the co-production of public services and strategy

- fostering the social economy

- age-friendly strategies

- bearing in mind all of the above, considering the need to rethink the strategy process in shrinking cities.

More specifically the chapter by Neill charts the reasons for the final coup de grâce of bankruptcy in the incredible shrinking city of Detroit. It argues that regional strategy is all-important and that development scenarios without cooperative metropolitan governance have ended in urban tragedy in Detroit. Detroit’s new small steps to recovery are reviewed and lessons for European practice drawn. The selection of Detroit as an American case study builds on previous work for the seminal major study of shrinkage by Oswalt (2006) where Detroit was painted as the nightmare which stalks the boundaries of European shrinkage discussion (Neill, 2006: 731–739).

Drawing on examples from the Czech Republic, Italy and East Germany Cortese et al. analyse the effectiveness of different local governance arrangements to facilitate social cohesion in the context of urban shrinkage. Their findings include that policy responses tend to be selective and sectoral, rather than comprehensive and focused on shrinkage. Hence cities try to address social cohesion through policies ranging from demolition and new build to active ageing and social inclusion initiatives, but struggle to put forward coherent social inclusion programmes that address the complex problems arising from long-term decline.

The chapter by Houston et al. argues that much is to be learnt from the long acknowledged challenges of shrinkage in rural contexts where, especially in fostering participatory forms of development, there is no need to completely reinvent the wheel. It examines how civic engagement can be allied to development strategies drawing in particular on the capacity building of citizens and the support of civil society organisations. The lessons for urban crossover from the EU LEADER programme are discussed in the context of the increasing urban purview of the EU policy outlook.

The following chapter by Murtagh shows that the social economy is a source of resilience shrinking cities can draw on. A range of issues central to the development of the social economy, including the encouragement of non-monetised trading, are discussed. Collectivised forms of non-monetised trading not only provide a deprived and often ‘cashless’ community with services but also show that monetary exchange and profit is not the only logic to supplying the things that local people need. Experience in the UK takes central place but with extensions made to the experience of shrinking cities in a broader European perspective.

Schlappa explores the practicalities of co-production in the context of urban shrinkage. Drawing on the case of a small manufacturing town in Germany he illustrates the challenges associated with overcoming often deep rooted denial of shrinkage, the prerequisite for a realistic baseline from which new strategies can be developed. The case study highlights the importance of demonstrating to citizens that public agencies are not im...