eBook - ePub

The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Prison

A Reader (2-downloads)

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book shows students that much that goes on in the criminal justice system violates their own sense of basic fairness, presents evidence that the system malfunctions, and sketches a whole theoretical perspective from which they might understand the failures and evaluate them morally.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Prison by Jeffrey Reiman,Paul Leighton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Readings on

Crime Control

in America

EDITORS’ INTRODUCTION

Chapter 1 of The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Prison has four main objectives: (1) examining the exclusive use of police and prison as the response to high crime rates in the United States, (2) reviewing the “excuses” that are made for the failure to significantly reduce our high crime rate, (3) discussing the known sources of crime and thus the kinds of policies that stand a good chance of reducing crime significantly, and (4) introducing the Pyrrhic defeat theory to explain the continued existence of policies that fail to reduce crime. The subtitle of Chapter 1, in our original text, The Rich Get Richer, is “Nothing Succeeds Like Failure,” which highlights an important aspect of the larger argument: The criminal justice system is allowed to continue to fail to reduce crime because this failure benefits those with power to change the system. Crime in the streets draws people’s attention away from crimes in the suites and, even more so, from the noncriminal harms that result from the actions of the well-off.

Crime rates have fallen noticeably since the early 1990s, and many believe this is because of the success of criminal justice policies, especially the increasing imposition of harsh prison sentences. The Rich Get Richer reviews some of the research showing that changes in criminal justice policy had little to do with the drop in crime rates, and Chapter 1 of this reader provides additional evidence so that criminology students can have a more sophisticated understanding of the dynamics behind the falling crime rates. This chapter also has several readings that highlight the important sources of crime, such as the availability of guns (which increase the temptation to crime and the harm that results from it), the illegality of drugs (which makes a criminal occupation more appealing to people with few alternative opportunities), the extent of poverty (which makes crime more tempting and staying straight less attractive), and the overuse of prison as well as prison’s harsh conditions (which harden inmates and make it harder for them to succeed legally once released). They all provide intervention points that could be used to reduce crime instead of exclusive reliance on police and prisons.

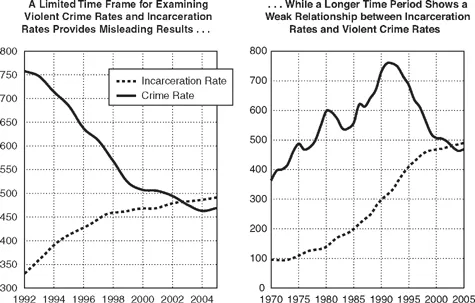

“Why Is Crime Falling—Or Is It?” by Alfred Blumstein is quoted in Chapter 1 of The Rich Get Richer in support of the assertion that increases in incarceration had little to do with the decrease in crime rates. Blumstein notes that attempts to show that increased incarceration leads to reduced crime mistakenly focus only on the period from 1991 on, which yields a “simplistic” understanding that creates “misleading” results. Crime rates started falling in 1991, so the increasing incarceration rates seem to be strongly related to a falling crime rate. Looking at a longer time period illustrates the weak relationship that Blumstein and others have found. This point is illustrated with updated data in Figure 1.1.

Blumstein presents a range of data and analysis based on a book he co-edited with Joel Wallman, The Crime Drop in America. Blumstein argues that “multiple factors” contributed to the crime drop, “including the waning of crack markets, the strong economy, efforts to control guns, intensified policing (particularly in efforts to control guns in the community), and increased incarceration.” Poverty lures many people into the drug trade but a strong economy supports the declining crime rate. His analysis implies that a great deal of drug violence could have been reduced if the drug trade were not illegal and drug dealers had legitimate means to resolve their disputes. Thus his analysis supports The Rich Get Richer’s contention that the illegality of drugs is a source of crime. Blumstein also notes that the proliferation of high-powered fast-action guns were a major cause of the increasing number of homicides and that successful efforts to control guns deserve some of the credit for the declining crime rate. Consequently, his argument is consistent with the notion that the availability of guns in the United States is a source of crime. Finally, some of the positive effects of incarceration on reducing the crime rate were “at least partially negated by violence committed by the replacements,” those individuals who are quickly recruited to take the place of imprisoned drug dealers. Indeed, because many replacements were young people, who have a greater propensity to settle disputes with violence, the net effect of imprisoning so many drug dealers may have been an increase in violent crime.

FIGURE 1.1 Incarceration and Violent Crime Rates for Different Time Periods

Source: Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics Online, Table 6.29.2006 and Table 3.106.2006. For an extended discussion of these charts, see Donna Selman and Paul Leighton, Punishment for Sale (Rowman and Littlefield, 2010).

The question mark in the title of Blumstein’s piece reflects caution based on the flattening out of crime rates in the preliminary data from 2000, the latest available when he did the presentation. Crimes rates did flatten out in 2000 and 2001, although violent crime rates finally bottomed out in 2004; property crimes increased from 2000 to 2001, then started declining again.

In “High Incarceration Rate May Fuel Community Crime,” Michael Fletcher of the Washington Post reports on a study suggesting that when many people from the same small community are taken out of that community and put in prison for crimes, the community itself is weakened in ways that may lead to crime. This early study making this link is supported by a growing body of evidence that under certain conditions high incarceration rates can have the unintended consequence of undermining the informal social processes that keep crime and other antisocial behavior in check. When many of the adults in a community are in prison, families are broken up, and because the vast majority of prisoners in the United States are men, there are fewer male role models for young people and fewer husbands for young women (some of whom are supporting children). Children are traumatized by the loss of a father, and more children grow up without ever having a man in the house. Criminology has well-developed theories about how social disorganization contributes to crime by eroding families and communities. Theories that link high incarceration to crime suggest that social disorganization arises from people being pulled out of the community into prison and dumped back into the community after a brutalizing prison experience.

Further, when many adults from a community are in prison, there is less money in the community, more poverty, and thus less trade to attract potential stores and businesses. Also, for purposes of the census, prison inmates are counted as residents of the county in which their prison is located, not where they lived before prison and will likely return. This practice inflates population counts in rural areas, where most prisons are sited, and causes changes in who gets elected and how federal aid grants are distributed and in other processes based on population. Cities then find themselves with more disorganization but less aid money and fewer elected representatives to advocate for help.

But perhaps the psychological effects are worst. With many adults from a community in prison, crime and imprisonment come to seem normal rather than exceptional. Youngsters growing up in such a setting come to think there is little they can do to avoid crime, little reason to try to avoid it, and little point to staying straight. This article should make readers wonder about the rationality of basing criminal justice policy exclusively on the idea of deterring crime by threatening lengthy prison sentences. Blumstein pointed out an unintended consequence of high incarceration rates was the increased violence from replacing older drug dealers with younger ones whose lack of maturity made them more prone to use lethal violence. Similarly, this article suggests the high incarceration rates in some communities have contributed to increased crime by undermining the ability of communities to raise and nurture lawabiding youngsters in the long run.

“From C-Block to Academia: You Can’t Get There from Here” is written by Charles Terry, one of a new breed of criminologists called “convict criminologists.” After spending much of his youth in prison because of drugs, Terry managed to get himself together, go to school, and get a Ph.D in criminology. He speaks about crime and punishment with a special kind of authority. He’s been there, on the other side. Terry tells here about his experiences with the criminal justice system. He makes it clear that convicts, even those who want to go straight, must fight an uphill battle that in most cases they will lose. Terry makes no excuses for his early criminality, but he describes as well how very little was done for him besides locking him up. He tells of the lack of support and encouragement, the absence of treatment programs for poor drug addicts, and of how the prison experience alienated him from the “straight” world. He tells of the difficulty of reentry and the ex-convict stigma. Terry’s struggle would be even more difficult today because the student loan programs he used to get an education and change his perspective are no longer available. About 700,000 people a year are released from prisons in the United States. With a prison record, and usually no job training, they face incredible obstacles to going straight. Is this intelligent social policy? Terry tells us it is not, and makes a number of suggestions to change prison, reentry, and even criminology itself. If we lock people up to prevent crime, shouldn’t we help them avoid crime when they are released?

In “A New Suit by Farmers against the DEA Illustrates Why the War on Drugs Should Not Include a War on Hemp,” Jamison Colburn introduces readers to a cost of the so-called “war on drugs” that they probably have not imagined. We know that the war on drugs costs billions of dollars, that it has largely failed to stem the drug trade, that it has led to the arrest and imprisonment of thousands of people who did nothing more than sell other people something that they wanted. But here is a cost of the war on drugs that you probably didn’t expect: Marijuana is made from the same plant from which we obtain hemp. Hemp is a very useful material, grown from time immemorial to make paper, canvas, rope, and seed oil with numerous uses. Moreover, hemp can be produced in a manner that is ecologically sound. Hemp cultivation is far less dependent on pesticides and herbicides than crops like cotton. But because hemp comes from the same plant that produces marijuana, U.S. farmers have been legally prevented from cultivating and marketing this valuable material even though industrial hemp has just a trace of the chemical THC that gives marijuana users a “high.” This article, written by a former lawyer for the United States Environmental Protection Agency, gives a useful history of the attempts to outlaw marijuana. Interestingly, lawmakers tried to exempt hemp production from the legal prohibition but were thwarted by government agencies such as the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) that appear in retrospect to have been uncritically opposed to anything even remotely related to marijuana, no matter how harmless, no matter how useful. The suit discussed in the article ends up being another unfortunate example of the negative consequences of criminal justice policy.

Currently, hemp products like fiber and oil are legal in the United States. However, cultivating them requires growing cannabis plants that have trace amounts of THC, which makes them a controlled substance under federal law. Thus, the United States imports hemp from countries such as Canada and China, which are among the thirty industrialized nations where it is legal to grow cannabis for hemp. To help their own farmers, North Dakota passed a law allowing for the cultivation of industrial hemp so local farmers could supply the hemp products we currently import, but federal drug law was still a potential barrier. The federal court decision in this case explains the controversy over the law:

The state regulatory regime provides for the licensing of farmers to cultivate industrial hemp; imposes strict THC limits precluding any possible use of the hemp as the street drug marijuana; and attempts to ensure that no part of the hemp plant will leave the farmer’s property other than those parts already exempt under federal law. The plaintiffs are two North Dakota farmers who have received state licenses, have an economic need to begin cultivation of industrial hemp, and apparently stand ready to do so but are unwilling to risk federal prosecution of possession for manufacture or sale of a controlled substance.1

The court dismissed the suit, thus not allowing the farmers to grow hemp. The court refers to the language of the Controlled Substances Act and prior cases interpreting the language to rule that the Act’s “definition of ‘marijuana’ unambiguously includes the Cannabis sativa L. plant and does not in any manner differentiate between Cannabis plants based on their THC concentrations.”

The court’s opinion states that “there may be countless numbers of beneficial products which utilize hemp in some fashion” and there is “little dispute that the retail hemp market is significant, growing, and has real economic potential for North Dakota,” but “the policy arguments raised by the plaintiffs are best suited for Congress rather than a federal courtroom in North Dakota.” Unfortunately, a bill that would have amended the Controlled Substances Act to allow for hemp farming, the Industrial Hemp Farming Act of 2007 (H.R. 1009), died in Congress without even a subcommittee hearing on its merits.

Note

1. Monson and Hauge v Drug Enforcement Administration and U.S. Dept of Justice, 522 F. Supp 2d 1188 (2007)

WHY IS CRIME FALLING—OR IS IT?

THE RECENT CRIME DROP

To those who worry about crime in the United States, the period from 1993 through 1999 was a welcome relief. We witnessed a steady drop in crime rates to a level lower than we have seen for more than 30 years. My presentation focuses on violent crime, primarily homicide, because it is so serious. It also is the most reliable and consistently measured crime and is highly correlated with many other aspects of crime. Between 1993 and 1999, the U.S. homicide rate dropped by an impressive 40 percent to a level of 5.7 per 100,000 population, a rate not seen since 1966. This almost brings the United States into the range of some of the countries in Western Europe….

These current favorable trends, however, cannot continue indefinitely. We should try to identify the factors that contribute to the downward trend and, as those effects are saturated, determine whether the downward trend will flatten or, because of other factors, reverse.

Whenever crime rates decrease, there are usually claims of both credit (e.g., “it’s a result of my administration’s policy of …”) and explanation (e.g., “demographic shift”). Television newscasters always look for a single explanation and are particularly troubled when more than two mutually supportive factors come together. I recently co-edited with Joel Wallman The Crime Drop in America,1 which...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Readings on Crime Control in America

- Chapter 2 Readings on A Crime by Any Other Name …

- Chapter 3 Readings on … And the Poor Get Prison

- Chapter 4 Readings on To the Vanquished Belong the Spoils

- Conclusion Readings on Criminal Justice or Criminal Justice