- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Automatic Fiscal Policies to Combat Recessions

About this book

Drawing on the most prominent research in the field, this timely book offers bold new fiscal policies that can complement current automatic stabilizers and counter-cyclical monetary policy to help combat recessions. Dr. Seidman argues for an independent fiscal policy board or the Federal Reserve to decide changes in the magnitude of Congress's fiscal policy package of stimulus or restraint, with recommendations going into effect immediately, subject only to Congressional override.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Automatic Fiscal Policies to Combat Recessions by Laurence S. Seidman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

1

Fiscal Policy to Combat a Severe Recession

Suppose the economy falls into a severe, prolonged recession. What should be done?

A half century ago, most economists would have prescribed a combined expansion of both fiscal and monetary policy—a money-financed fiscal stimulus. In the past few decades, however, many economists have ignored fiscal policy and recommended sole reliance on a monetary expansion; some economists have contended that simply keeping the money supply from contracting would be sufficient. This chapter makes the case for implementing a money-financed fiscal stimulus to combat a severe, prolonged recession.

Krugman’s Challenge

In an article titled, “It’s Baaack: Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap,” Paul Krugman (1998) asks whether monetary policy has the power to rescue a depressed economy when the interest rate is already near zero. John Maynard Keynes, observing the near-zero interest rates during 1930s, argued that monetary policy alone could not revive an economy mired in such a “liquidity trap.” Krugman says that since World War II the liquidity trap has generally been unimportant because interest rates have stayed well above zero. He notes that most modern macroeconomists think that a liquidity trap “cannot happen, did not happen, and will not happen again” (1998, 138). He then says, “But it has happened, and to the world’s second-largest economy.” He points out that over the past few years, Japanese money market rates have been below 1 percent, yet the Japanese economy has remained depressed for a decade. Krugman warns that if this can happen to Japan, it can happen elsewhere.

Krugman is surely correct that policy makers should be ready to revive a depressed economy in which the interest rate is very low. He acknowledges that economists in the Keynesian tradition have prescribed a simple straight-forward solution: expansionary fiscal policy. Expansionary fiscal policy means either a cut in taxes, or an increase in government cash transfer payments, or an increase in government purchases of goods and services. Tax cuts and cash transfers should raise consumer spending, stimulating production of consumer goods, and in turn inducing businesses to raise their investment spending in order to develop the capacity to produce these consumer goods. Government purchases stimulate the production of the goods that the government buys. All of this generates income that in turn further raises consumer spending.

But rather than simply recommend this straightforward solution, Krugman surprisingly chooses to investigate the problem in a “modern” macroeconomic model in which fiscal expansion does not work. A key element of this “modern” model is the unrealistic assumption of Robert Barro (1974) that people will entirely save any tax cut or cash transfer. Why would people, who usually spend most of their disposable income and save only a small portion, now save all of their additional disposable income and spend none of it? According to Barro, it is because the typical person would say to himself, “If the government leaves me with more cash today (either by cutting my tax or sending me a cash transfer), it will have to borrow more today and will therefore have to tax me more tomorrow to pay back its debt; so I better set aside all of the cash I get today so that I am ready to pay the tax tomorrow.” Barro, however, has never provided any empirical evidence whatsoever that people (other than a few economists) actually think this way.

Krugman knows Barro’s assumption is unrealistic, but he finds it intellectually challenging to figure out how to rescue a depressed economy in a liquidity trap without using fiscal policy. How can it be done? Krugman says by having the central bank announce it will bring about a steady inflation of 4 percent per year for a decade and a half. Why will this work? According to Krugman, the central bank’s announcement will cause people to believe there will be 4 percent inflation, and this belief will cause them to borrow and spend. Thus, two things must happen for Krugman’s plan to work: people must believe there will be 4 percent inflation, and this belief must induce them to borrow and spend more. Each can be questioned.

First, will the central bank’s announcement actually raise the inflation rate that people in Japan expect? In the discussion following Krugman’s presentation of his paper at the Brookings panel, several panel members were skeptical. Robert Gordon doubted that the Bank of Japan can easily change inflationary expectations because expectations depend largely on actual experience, and actual inflation will rise only when there is excess demand in the markets for goods and labor. I interpret Gordon’s comment this way: There is no magic connection from a central bank’s increase in high-powered money to a rise in the price of goods and services; only if the central bank’s action actually raises people’s demand for goods and services will it result in a rise in the price of goods and services. Hence, people are right to be skeptical about whether the central bank, with the nominal interest rate near zero, has the power to raise the price of goods and services. Alan Blinder noted that Krugman’s policy would require the Bank of Japan to persuade people that the future was going to be fundamentally different from the past because Japan has had no inflation for most of the 1990s. Martin Baily said that it would be easy for Russia to be credible in announcing inflationary policy but hard for Japan.

Second, even if the announcement causes people in Japan to believe there will be 4 percent inflation, will this belief induce them to borrow and spend more? Many economists contend that people “should” borrow and spend more if they suddenly expect more inflation, because people “should” look at the “real” interest rate—defined as the nominal interest rate minus the expected inflation rate—not at the nominal interest rate per se, and a rise in expected inflation, by definition, reduces the real interest rate. Thus, many economists contend that a rise in expected inflation from 0 percent to 4 percent “should” do as much to stimulate borrowing and spending as a cut in the nominal interest rate from 4 percent to 0 percent. But will it? It is obvious to the ordinary person that a cut in a bank’s interest rate from 4 percent to 0 percent makes it a better time to borrow. But it may not be obvious to the ordinary person that expected inflation is a good reason to borrow and spend more.

Krugman concedes that in the actual economy a fiscal policy would do some good and should therefore be utilized, but he worries about whether fiscal policy can be sufficiently expansionary in practice. He notes that to cure a severe recession a successful fiscal expansion might have to be large and continue for several years. He wonders whether the consequences in terms of government debt are acceptable, and whether any Japanese government would have the “political nerve” (1998, 178) to propose a fiscal package large enough for long enough to cure a stubborn recession.

Gordon’s Reply

Krugman’s concern about running up too much debt with an expansionary fiscal policy is directly addressed by Robert J. Gordon (2000). He compares Japan in the 1990s to the United States in the 1930s. Although Japan’s slump has not been nearly as deep as the Great Depression, it also has lasted a decade. In both cases, interest rates have been very low. The Japanese short-term interest rate fell below 1 percent after 1995 and in 1996–99 was roughly constant at about 0.5 percent. In the United States the short-term interest rate fell below 1 percent after 1931 and in 1938–40 was less than 0.05 percent. Gordon says that if monetary policy is impotent because it cannot reduce the interest rate any further, a fiscal stimulus is required to end the slump. Gordon notes that the Japanese government appears hesitant to propose a large fiscal stimulus because the public debt in Japan, roughly 100 percent of GDP, is high among economically advanced countries.

But Gordon argues that this reluctance is mistaken, provided the fiscal stimulus is combined with a monetary expansion. He makes this crucial point that with a joint fiscal/monetary expansion there is no need for a further increase in the national debt held by the public, because to achieve its monetary expansion, the central bank can buy the government bonds issued as a result of the increased fiscal deficit. Gordon notes that Japan has not pursued this “obvious solution.” Why not? The joint fiscal/monetary expansion requires the Bank of Japan to buy up the government bonds issued when the government spends more than it taxes, and this purchase of bonds by a central bank is sometimes called “monetizing the debt.” Historically, excessive infusion of money into an economy has often led to high inflation, and apparently the Bank of Japan seems reluctant to do it.

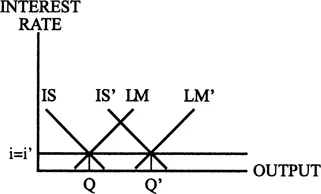

Gordon explains his prescription in terms of the standard textbook IS/LM diagram shown in Figure 1.1. In that diagram, the interest rate is plotted vertically and output horizontally. The IS curve has a negative slope and the LM curve has a positive slope. The intersection of the IS and LM curves determines the interest rate and output of the economy. The IS curve embodies spending by consumers, businesses, and government. A fiscal stimulus (a tax cut or increase in government spending) shifts the IS curve to the right, thereby raising output (while raising the interest rate). The LM curve embodies monetary policy. A monetary stimulus (engineered by the Federal Reserve System through open market operations) shifts the LM curve to the right, thereby raising output (while lowering the interest rate). Now note a key point. As the monetary stimulus is raised further, the LM curve shifts further right, and the intersection with the IS curve occurs at a still lower and lower interest rate. When the intersection finally occurs at a zero interest rate, there is nothing more that monetary policy can do to raise output, because no matter how much money is injected into the banking system by the Federal Reserve, banks will not reduce their interest rate below zero; after all, what bank would lend $100 if the borrower agrees to repay only $99, implying an interest rate of -1 percent? Thus, the most monetary policy can do is raise output to point where the IS curve intersects the horizontal axis.

Figure 1.1 shows the problem for monetary policy in Japan in the 1990s and the United States in the 1930s. In both cases, a stock market plunge, bank failures, and consequent pessimism caused consumers and businesses to reduce their spending so much that the IS curve shifted so far to the left that it intersected the LM curve at a very low interest rate and low level of output. The most monetary policy can do is nudge the interest rate to zero, resulting in only a slight increase in output. The fundamental problem is the position of the IS curve—it is too far to the left—and as long as it stays there, monetary policy will be powerless to cure the recession. The solution should be evident: shift the IS curve right to IS’ with fiscal policy, and shift the LM curve right to LM’ with monetary policy.

Figure 1.1 IS/LM Diagram

Gordon writes:

If monetary policy is impotent because it cannot reduce the interest rate any further, a fiscal stimulus is required to end the slump and bring the output ratio [the ratio of actual output to “natural output”] back to its desired level of 100 percent….The low level of the Japanese interest rate created a policy dilemma in Japan. Monetary policy could not push interest rates appreciably lower, yet fiscal policymakers felt constrained in achieving a large fiscal stimulus by the high existing level of the fiscal deficit in Japan and by the fact that the public debt in Japan had reached 100 percent of real GDP.However, the IS-LM model suggests a way ou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- References

- Index

- About the Author