![]()

1

___________________________

The Emergence of Sustainable Strategic Management

Case Vignette 1

Creating Value Through Sustainability at Eastman Chemical Company

Jim Rogers, chairman and chief executive officer (CEO) of Eastman Chemical Company, contemplated the question and then responded, “Sustainability is an area where we can show our hearts but use our brains. We show our hearts by doing things that protect the next generation of the world that we live in—things like reducing greenhouse gases, volatile organic compounds, and energy use. Sure, this saves us money, but we know it is the right thing to do. However, the fun part is when we get to use our brains, which involves looking for ways to drive growth with sustainability. Doing this means giving our customers what they want so that they can ride the sustainability wave with us. We want to be right there alongside our customers helping them drive sustainability as a competitive advantage.”

Rogers went on to say, “Sustainability is a mega trend sweeping over our industry and many others. It makes sense for our business, it makes sense for our world, and it is very consistent with Eastman’s culture of continuous improvement, innovation, and responsibility.” He pointed out that Eastman has made significant progress in its sustainability efforts over the past year, including naming Godefroy Motte chief sustainability officer (CSO). According to Rogers, Motte, who is located in the Netherlands, “brings with him Europe’s pioneering sustainability thinking and a personal passion for sustainability.”

In commenting on his firm’s commitment to sustainability, Motte said, “Eastman is an advanced materials and specialty chemical company developing innovative, sustainable solutions to improve the world. As such, sustainability has become an integral part of what we do—it is part of our DNA. Thus sustainability has become an important driver of our new product developments. We are working hard to create value through environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and economic growth both now and for future generations.” Motte further points to the fact that Eastman’s sustainability efforts are not new. He said, “We’ve been an active participant in the chemical industry’s voluntary Responsible Care® initiative for nearly a quarter of a century. After all, sustainability is an attitude and not just an activity to participate in from time to time.”

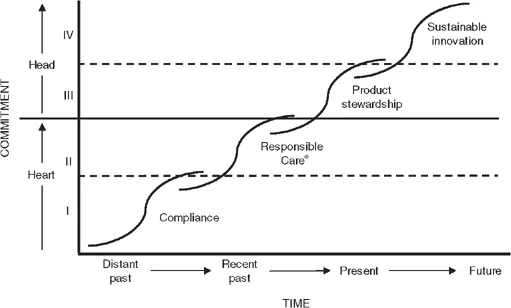

Case Exhibit 1.1 Eastman Chemical Company’s Sustainability Evolution

Motte expanded on Roger’s point that Eastman’s commitment to sustainability has coevolved to include both doing what is right for current and future generations—working from the heart—and creating innovative new products that protect nature, improve society, and create economic value for Eastman and its customers—working from the head. He said that he sees Eastman’s sustainability journey as progressing through four stages: Compliance, Responsible Care®, product stewardship, and sustainable innovation (see Case Exhibit 1.1).

Both Rogers and Motte described the first two stages as coming from the heart—doing what is right regardless. Compliance, obeying the law, is certainly the right thing to do, but it is also quite expensive. Nonetheless, they both pointed out that compliance was the primary sustainability focus of the chemical industry until the 1984 explosion at Union Carbide’s pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, which killed thousands of people and exposed hundreds of thousands to methyl isocyanate and other deadly chemicals.

This incident and others like it, along with an increasingly complex and expensive regulatory environment, became imminent threats to the chemical industry in the 1970s and 1980s. Thus, in the late 1980s, chemical firms, including Eastman, joined together under the auspices of the American Chemistry Council (known then as the Chemical Manufacturers Association) and established the Responsible Care® program, which helped shift the industry’s sustainability focus from regulatory compliance to voluntary ecological and social responsibility. Not only did Responsible Care® significantly improve the image of the chemical industry during some of its darkest days, it also encouraged firms to find ways to create value via improved ecological and social performance (i.e., energy reduction, resource reduction, pollution prevention, materials substitution, employee safety, community safety, improved community relations, etc.).

Such efforts are now central to the design and function of Eastman’s products and processes. For example, the firm was named an EPA Energy Star® Partner of the year in both 2012 and 2013, was actively involved in the European Chemical Industry Council’s (CEFIC) Build Trust program, and reported its sustainability activities to the Global Reporting Initiative for the first time.

Motte believes that Eastman has fully embraced the two heart stages and is currently operating in the first head stage—stage three—product stewardship. This stage involves the firm’s taking full stewardship of the value chain by working with customers to provide sustainable solutions and by providing life cycle analysis (LCA) data to help customers reduce their footprints. Tritan™, a BPA-free plastic for containers, and Perennial Wood™, an ecologically safe alternative to pressure-treated lumber, are two examples of what Eastman refers to as “sustainably advantaged” products that have recently emerged in this stage.

Eastman now wants to move into stage four, sustainable innovation, which involves establishing ecological and social sustainability all along its value chain and serving customer needs in all global markets, including the base of the economic pyramid. For example, the HydroPack™ (discussed further in Case Vignette 5) resulted from a partnership between Eastman and its customer Hydration Technology Innovations to provide clean drinking water for disaster victims. Also, Eastman is currently working with a diaper manufacturer to develop a more affordable, eco-friendly diaper, which is a desperate need for BoP customers. In commenting on Eastman’s desire to fully embrace stage-four sustainability, Motte said, “It is an opportunity to use our creativity and innovation to be part of the solution, for our world today and for future generations.”

___________________________

Eastman’s sustainability journey is typical of firms in its industry. All organizations survive by successfully adapting to changes in the business environment, and the environment of the chemical industry has become progressively more sustainability demanding over the past half century (Hoffman 1999). The dangers of its products and by-products were exposed by Rachel Carson in Silent Spring in 1962, and they were again brought to the headlines in the 1970s and 1980s with issues like Agent Orange, Love Canal, and Bhopal. Chemical tragedies like these eventually led to a regulatory environment in the industry that was oppressively expensive. Firms in the industry responded to these dire events and costly regulations by implementing strategies and processes designed to reduce both their regulatory burdens and their costs of environmental management. Strategies implemented included reducing or eliminating wastes and toxins, reducing energy, and making other improvements in their environmental performance. Thus, firms in the industry began seeking competitive advantages via total product stewardship. Today chemical firms in the industry are beginning to seek competitive advantages by innovating new products and processes that will allow them to expand into previously ignored markets, including those heavily populated markets at the base of the pyramid (BoP).

Unfortunately, sustainability is not just a chemical industry issue. If it were, achieving it would be simple. But sustainability—typically defined as providing a high quality of life for current and future generations—is a global issue that involves all people and all business organizations. Sustainability is more a global vision of the future than a specific state of being, and it is usually portrayed as having three interdependent dimensions: the economy, the society, and the natural environment. The interactions among these dimensions are complex, and many of these interactions lie outside the realm of traditional business models.

Sustainability has grown from a fringe issue in the 1970s to a central issue in the global consciousness today (Aburdene 2005; Edwards 2005; Hawken 2007; Senge et al. 2008; Speth 2008). Paul Hawken (2007, 12) says, “Social and cultural forces are currently converging into a worldwide movement that expresses the needs of the majority of people on Earth to sustain the environment, wage peace … and improve their lives.” Of course when an issue becomes central in society, it becomes an important part of the business strategy landscape (Kiron et al. 2013). Peter Senge (2011) says that the rising sustainability consciousness is a “profound shift in the strategic context” of business organizations, and two recent surveys of global business executives bear him out. In the first survey (Kiron et al. 2012), 90 percent of the 2,874 responding executives said that implementing sustainability strategies is now or soon will be a competitive necessity for their organizations, and 70 percent said that they have put sustainability on their strategic agendas within the past six years. In the second survey (Kiron et al. 2013), 50 percent of the 2,600 responding executives said that they had changed their basic business models to incorporate sustainability because of the strategic opportunities that it provides them, a full 20 percent increase over the previous year’s survey. Data such as these leave little doubt that the 2012 survey researchers were correct when they concluded, “The sustainability movement [is nearing] a tipping point” (Kiron et al. 2012, 69).

The Changing Economic Worldview

Reaching that tipping point has taken humankind about 350 years. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, humans have built their hopes and dreams on a worldview that unlimited economic growth is possible and desirable forever. This belief in the possibility and desirability of unlimited economic growth has led to the global belief that more production and consumption are good regardless of the environmental and social consequences. Gross domestic product (GDP) is viewed as a measure of pure good, regardless of what actually constitutes it. Indeed, in today’s world, personal and societal welfare are measured almost solely on economic growth factors.

So this longstanding worldview encourages humans to produce and consume, produce and consume, produce and consume, at breakneck speeds. Whereas doing so in early economic history when few nations and few people were participating in economic activity is understandable, humans today clearly realize that their economic activities are threatening the very resources and systems that support quality human life on the planet. If humans continue to foul the air and water, degrade the land, ignore the poor and disenfranchised, and exploit the natural beauty, they are in danger of leaving a world to their future generations that is not as hospitable to humans as the one they inherited from their ancestors.

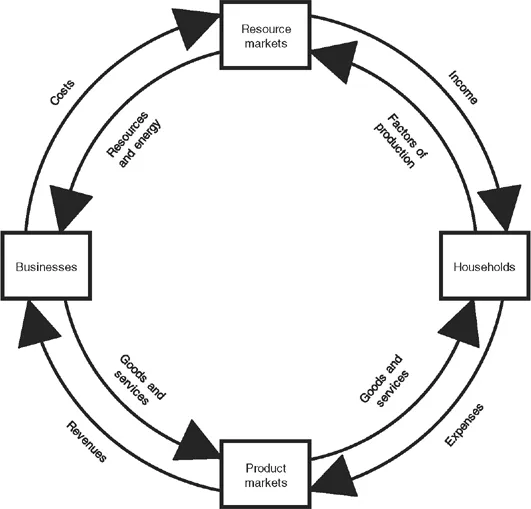

At the heart of the worldview that has guided strategic decision makers over the past 350 years is the image of the economy as a closed circular flow (see Figure 1.1). This framework depicts the production-consumption cycle in which resources are transformed by business organizations into products and services that are purchased by consumers. Note in the model that resources flow in one direction and money flows in the other. The problem with the closed circular flow model is not what it depicts, but what it ignores. Depicting the economy as closed implicitly assumes that the economy is isolated and independent from the social system and ecosystem. Under such an assumption, the economy is not subject to the physical laws of the universe, the natural processes and cycles of the ecosystem, or the values and expectations of society. Assuming these away leaves humankind with a mental model of an economy that can grow forever as self-serving insatiable consumers buy more and more stuff from further and further away to satisfy a never-ending list of economic desires without any serious social and ecological consequences.

Figure 1.1 The Closed Circular Flow Economy

Unfortunately the economy is not isolated from the earth’s other subsystems as depicted in the closed circular flow model. Now is the time to break free from the mythic drive for economic growth in favor of a new economic worldview, one based on the image of an interconnected global community of people functioning in harmony with one another and with nature. Long-term economic health is possible under this worldview only if the social system and ecosystem can support it. Thus global economic activity has to function within the natural and social boundaries of the planet. The earth is the ultimate source of natural and human capital for the economic system. Thus, a healthy flow of economic activity can be sustained for posterity only if strategic decision makers operate under the paradigm that the economy serves the needs of the greater society within the limits of nature.

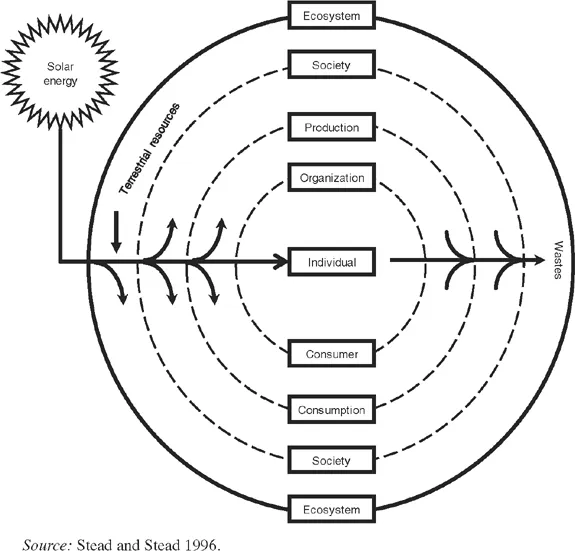

Figure 1.2 The Open Living System Economy

Source:Stead and Stead 1996.

Figure 1.2 depicts such a worldview. In this model, the earth is a living system. As such, its survival is dependent on achieving a sustainable balance within its various subsystems. The most basic living subsystems on the planet are the individual organisms that inhabit it, and the most dominant of the planet’s individual organisms is humankind. Because of this dominance, the decisions made by human beings are major forces influencing the ultimate state of society and nature. The ability of human beings to make effective decisions about how they interact with one another and with the planet depends on the accuracy of the mental processes they use to make those choices. At the heart of these mental processes are the underlying assumptions and values human beings hold. Thus, human values and assumptions have a huge influence on the state of society and nature.

Of course, humans make their decisions in a variety of collective contexts. Decisions are made in the context of families, business organizations, educational institutions, governmental agencies, and interest groups, to name but a few. In the economic realm, individuals make decisions as members of organizations that produce goods and services, and they make decisions as part of the collective of consumers who purchase and use...