eBook - ePub

Women in World History: v. 1: Readings from Prehistory to 1500

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women in World History: v. 1: Readings from Prehistory to 1500

About this book

Presenting selected histories in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas, this work discusses: political and economic issues; marriage practices, motherhood and enslavement; and religious beliefs and spiritual development. Famous women, including Hatshepsut, Hortensia, Aisha, Hildegard of Bingen and Sei Shonangan, are discussed as well as lesser known and anonymous women. Both primary and secondary source readings are included.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women in World History: v. 1: Readings from Prehistory to 1500 by Sarah Shaver Hughes,Brady Hughes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

–1–

PREHISTORIC WOMEN

Shaping Evolution, Sustenance, and Economy

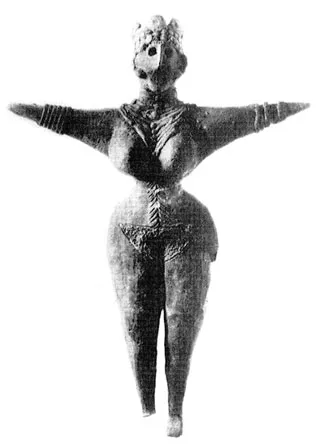

A 2,000-year-old figurine from a Bronze Age tomb in present-day Iran. (UPI/Bettmann, photo © 1975 by Andreas Feininger from his book Roots of Art.)

When anthropologists and archaeologists explain the origins of human societies, “man the hunter” is the dominant figure. The meat he lugs to the family fire sustains his dependent wife and children. The powerful image of his protective brawn pervades Western culture from cartoons to serious science. A weak, subordinant woman is his implied mate: someone whose dull, repetitive chores need not be discussed because she contributed nothing to culture, history, or civilization. The assumption that the representative human being is male is rooted in nineteenth-century speculation about the beginnings of human cultures. In the past twenty-five years, some scholars have worked from different assumptions. What if “woman the gatherer” returned to camp with most of the family food? What if women’s choices were fundamental to human evolution? What if the first great human technological revolution—the discovery of agriculture—was carried out by women? What if the earliest economic development of human societies was based on trade in surplus food and textiles produced by women?

Much of the writing of archaeologists and anthropologists is speculative, so assumptions matter. Stone ruins, burials, broken pots, fragments of cloth, and arrowheads can reveal material cultures of the prehistoric past, but they do not speak directly of the social environment. Who chipped the arrowhead, shaped the clay, wove the cloth, shrouded the body, lifted the stones? Usually there is no way to know the answers to these questions. Scientific analysis has transformed the study of prehistory in the past fifty years: radiocarbon dating and physical and chemical studies of trace elements in pottery shards, human bones, and ancient seeds have solved many old puzzles about when settlements were built and what botanical and mineral resources were available.

Less progress has been made in gendering the prehistoric past. The gender and age of skeletons are routinely considered today when graves are opened, and it is possible to determine by carbon isotope values and chemical analysis whether men or women, adults or children, were fed better during their lifetimes. Until new techniques permit analyses to determine the sex of fingerprints or other molecular residues, no one can tell us whether women or men created the baskets, pottery, cloth, or metal artifacts of a prehistoric people. Even when that is known, interpretation and assumptions will guide teasing out the motivations underlying a social structure. New techniques and more evidence may fail to yield a better understanding of prehistoric peoples unless there is an acknowledgment of present androcentric biases.

1.1 Women in the “Gatherer-Hunter” Phase

Before we can confidently say what gender had to do with human accomplishments in any prehistoric period or place—or how gender patterns may have changed over many thousands of years—we need to free our minds from stereotypes of “man the hunter,’ as Adrienne Zihlman illustrates.

About 5 million years ago forest-ranging, knuckle-walking apes—very much like living chimpanzees—evolved through the process of natural selection into the earliest humans, the hominids, who walked upright on two legs, used tools, and lived and gathered food on the African savannas. Females, so long ignored in evolutionary reconstructions, must have played a critical role. Influencing the evolutionary direction of the species, they invested time and energy in their offsprings’ survival (maternal investment) and chose as their mates those males more protective and willing to share food than the average male ape (sexual selection). Whereas male apes depart from their mothers and siblings at puberty, male hominids were integrated along with the females into their mothers’ kin group and contributed to the survival of long-dependent young (kin selection). These relatively sociable males probably became the preferred sexual partners of females in neighboring groups, and, in this way, reinforced the evolutionary process by changing human males through sexual selection.

The presently popular “hunting hypothesis” of human evolution argues that hunting as a technique for getting large amounts of meat was the critical, defining innovation separating early humans from their ape ancestors. This view of “man the hunter” has been used to explain many features of modern Western civilization, from the nuclear family and sexual division of labor to power and politics. But as more and more data have accumulated in recent years, and as approaches to them have changed, the notion that early “man” was primarily a hunter, and meat the main dietary item, has become more and more dubious. Consequently, interpretations of early human social life and the role of each sex in it must be reevaluated. The usual question in most interpretations of human prehistory is “What were the women and children doing while the males were out hunting?” Here I ask instead, “How did human males evolve so as to complement the female role?”

Even without fossil evidence, Darwin deduced that bipedalism and tool using must have been early characteristics of the human line which originated in Africa. Evidence supporting his hypothesis began turning up in South Africa in the 1920s. In the past two decades, hundreds of hominid fossils and thousands of stone tools have been unearthed in both East and South Africa. Our early ancestor, Australopithecus, “southern ape,” was neither ape nor exclusively southern. It had a brain size that was a little larger than that of the apes, but was entirely bipedal, with small unapelike canine teeth and large molar and premolar teeth—similar to those of plant-eating, not meat-eating animals.… During the past decade, new fossils, dating between 1 and 4 million years old, have been coming to light in Africa at a rapid rate. The time span of these fossils is consistent with the biochemically estimated divergence of humans from African apes about 5 million years ago.…

The African savanna, where all these fossils have been found, consisted then as now of grasslands, low bush, and riverine forests—a mosaic of vegetation types.… The diversity of plant, and consequently animal, life on the savanna presented an opportunity to the evolving and omnivorous hominids for exploiting these abundant resources.

We cannot escape the evolutionary implication that, to some extent, we are what our ancestors ate. Among the hominids, social organization would have been different if the diet was mostly vegetarian than if the diet was primarily one of meat acquired through hunting. The importance of plant food in the diet of early hominids has long been acknowledged, but its significance tended, until recently, to be obscured by the overemphasis on meat and hunting. The fallacious picture of early hominids as a newly emerging meat-eating primate is refuted not only by their omnivore-like masticatory system but also by numerous observations on predation and meat-eating in chimpanzees and baboons—a confirmation of the principle of evolutionary continuity. Studies of living peoples who gather and hunt reveal that throughout the world, except for specialized hunters in arctic regions, more calories are obtained from plant foods gathered by women for family sharing than from meat obtained by hunting. Due to the relative durability of bone as opposed to plant refuse, the archaeological record may exaggerate the amount of meat in the early hominid diet.

Adrienne L. Zihlman, “Women in Evolution, Part II: Subsistence and Social Organization among Early Hominids,” Signs 4 (1978): 4–7. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, the University of Chicago. © 1978 by the University of Chicago.

________________

Part of the “man the hunter” argument was based on the numerous collections of animal and hominid bones found together in African sites. Archaeologists who have examined the bones more carefully have argued that they are not the hominid hunter’s trash pile but the predator’s garbage. And the hominid remains in the piles are those of the victims, not the victors.

Although there is no direct evidence for australopithecine predation or for bone and stone toolmaking before about 2 million years ago, it is likely that, continuing the ape ancestral pattern, they engaged in predation and making tools, albeit of organic materials. Tools for digging and carrying food meant that greater quantities could be collected for sharing. Large carnivores posed a real danger on the savanna. Therefore part of the food-getting process had to include the ability of hominids to protect themselves. Their small canine teeth, integral to the food-grinding mechanism, also imply that they used means other than physical prowess in predator defense. Both females and males could deal with predators in a variety of ways: by avoiding them and being active during the day; by traveling, sleeping and getting food in the company of several other individuals and so finding safety in numbers; or, in the event that a confrontation occurred, throwing objects as part of threatening, noisy displays not unlike the bipedal, branch waving and object throwing of chimpanzee displays.

The hominid way of life, which relied on bipedalism and tool using, required a long period for the young to learn and develop associated motor patterns before they were completely independent, perhaps not before eight or ten years of age.

Adrienne L. Zihlman, “Women in Evolution, Part II: Subsistence and Social Organization among Early Hominids,” Signs 4 (1978): 7–8. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, the University of Chicago. © 1978 by the University of Chicago.

________________

Human children must be carried for three to five years, and they lack the endurance to take long walks at the adult’s pace until they are eight at least. Furthermore, they probably cannot master the use of even simple tools before they are five years old.

The early hominids, whose way of life depended upon making and using tools both for obtaining and preparing food and for using objects in defense, must have required even more time to learn such skills. A long dependency prior to walking long distances and mastering tools meant a major investment by mothers in each offspring—in time and energy and in physical, social, and economic efforts.

There is no evidence that, at this early time in prehistory, australopithecine “campsites” or “home bases” existed where the young could be left by mothers and cared for by other group members, as is typical of Kalahari gatherer-hunters today. The burden of child care could only have been possible, I propose, if care was shared by other group members who, at this stage, were close kin. Males who were brothers and sons of the females were regular members of the kin group. Their roles in socialization and care of the young, defense, obtaining meat, sharing food, and, perhaps, collecting raw materials, were significant contributions to the group as a whole. Thus male and female kin contributed to the survival of their young relatives. With this support, mothers could have another offspring before the previous one was entirely independent. Without this involvement of kin—a social solution to a physical problem—birth spacing would have to be extended to more than three or four years, leaving little time for reproduction in a species whose life span may have been little more than twenty years.

Australopithecine females and males had similar-size canine teeth and no more than moderate differences in body size, that is, minimal sexual dimorphism. The degree of sexual dimorphism in canine teeth and body sizes, within the many monkey and ape species studied, correlates with behavioral differences in predator defense and social roles. The small canine teeth in early hominids must be related to three things: diet and mastication, predator defense, and mating patterns. First, the reduced canines in both sexes of early hominids … function as part of the biting and grinding mechanism. Second, large male canine teeth and body size differences, as in baboons, function as part of the species’ defense system. For the hominids, predator defense would have little anatomical basis. Both sexes probably engaged in a variety of antipredator behaviors. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the small canines of male hominids suggest that they were more sociable and less aggressive in their interactions with other males and with females. They probably competed with each other for mating with females in agreeable ways rather than by overt fighting or dominance behavior as monkeys and apes do. Hominid male sociable behavior would be advantageous, and indeed necessary, for integration initially into their kin groups and, subsequently, into larger social groupings. Females most frequently chose sexual partners from among the sociable males outside the immediate kin group.… Sexual behavior then, as now, was only one expression of social bonds between females and males.

Adrienne L. Zihlman, “Women in Evolution, Part II: Subsistence and Social Organization among Early Hominids,” Signs 4 (1978): 8–10. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, the University of Chicago. © 1978 by the University of Chicago.

________________

In this model the formation of sharing food networks and family units should be clarified.

Sharing food among the nonhuman primates is infrequent and is of social, rather than nutritional, significance. The new and fundamental elements in the human way of life included food sharing as a matter of survival, regular sharing between mother and offspring, and the expansion of sharing networks to include adult females giving to adult males. This latter kind of sharing may have developed initially within the kin group: mothers gave to their young male offspring and continued to do so when they grew up and stayed with the mother-centered group. Females also shared with their male siblings. Later these behaviors would be a basis for generalizing the sharing with adult males outside the immediate kin group.

Adrienne L. Zihlman, “Women in Evolution, Part II: Subsistence and Social Organization among Early Hominids,” Signs 4 (1978): 10. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, the University of Chicago. © 1978 by the University of Chicago.

________________

In the “man the hunter” hypothesis, both economic and reproductive functions occur in the nuclear family, just as they do today.

I propose, alternatively, that among the australopithecines the economic units were primarily the smaller kin groups that shared plant and animal foods and cared for the young. Sexual behavior and the “reproductive units” occurred within the larger associations of unrelated individuals who came together in their kin groups at food and water sources and sleeping places. These two units became linked much later in time and, even then, only in some societies.

A picture then emerges of a cooperative, sociable kin group of both females and males learning to make and use tools; opportunistically gathering food of many plant types covering a large range on the savanna; sharing plant and animal foods; and defending themselves in conjunction with other kin groups more or less effectively against the lions, leopards and hyenas which were even more abundant then. The presence of males, unencumbered by infants, would have enhanced the survival of such a group. They could range farther in search of food, help care for the young, and contribute to defense against predators.

Adrienne L. Zihlman, “Women in Evolution, Part II: Subsistence and Social Organization among Earl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword by Kevin Reilly

- Preface

- Introduction: Gendering World History, Globalizing Women's History

- 1. Prehistoric Women: Shaping Evolution, Sustenance, and Economy

- 2. The Women of Ancient Egypt

- 3. India: Women in Early Hindu and Buddhist Cultures

- 4. Israel: Jewish Women in the Torah and the Diaspora

- 5. Greece: Patriarchal Dominance in Classical Athens

- 6. China: Imperial Women of the Han Dynasty (202 B.C.E-220 C.E.)

- 7. Women in the Late Roman Republic: Independence, Divorce, and Serial Marriages

- 8. Western Europe: Christian Women on Manors, in Convents, and in Towns

- 9. The Middle East: Islam, the Family, and the Seclusion of Women

- 10. China and Japan: The Patriarchal Ideal

- 11. Africa: Traders, Slaves, Sorcerers, and Queen Mothers

- 12. Southeast Asia: The Most Fortunate Women in the World

- 13. The Americas: Aztec, Inca, and Iroquois Women

- Glossary

- About the Editors