![]()

Part I

Building Types

Chapter 1: The Emergence of the Tropicalized House

Comfort in the Heteronomous and Heterogeneous Conditions of Colonial Architectural Production

The earliest architectural historical accounts of colonial architecture in Singapore are those written by T. H. H. Hancock, a Senior Architect with the colonial Public Works Department (PWD), during the 1950s on the early nineteenth-century buildings erected by George Doumgold Coleman, purportedly the first architect of Singapore.1 Hancock was involved in the mid-twentieth-century remodeling of the Legislative Assembly building, which was previously Maxwell House designed by Coleman.2 That undertaking might have led him to research on Coleman and his works. With the research, Hancock argued that Coleman was central to the creation of a “tropical Colonial style.”3 In an exhibition catalogue on what was probably the first architectural exhibition in Singapore, Hancock summarizes the “tropical Colonial style” in the following manner:

Coleman and his immediate successors skillfully adapted the Palladian manner to suit the tropics. These early architects, skilled in classical proportions, developed a Colonial classic idiom with the solidity of the Doric order, with deep and wide verandas and hooded openings for shade, single room thickness for through ventilation and louvred windows to give light, yet reducing glare, and for protection from sudden heavy rain storms.4

This “tropical Colonial style” was seen essentially as an outcome of Coleman’s adapting Palladianism to the climatic conditions of the tropics so as “to provide conditions of maximum comfort for [Coleman’s] clients and their families.”5 Perhaps because little was written about Coleman and early colonial architecture in Singapore until Hancock started doing so in the 1950s, Hancock’s trailblazing accounts became very influential. Many architectural historians writing about Singapore’s colonial architecture subsequently repeat – sometimes without attribution – Hancock’s argument that Coleman was solely responsible for adapting Palladianism to the tropical climate of Singapore. For example, local historian Marjorie Doggett writes that Coleman “developed a colonial classical idiom with wide verandahs for shade, and louvred windows to reduce glare, give protection against torrential rains and provide adequate through ventilation.”6 Likewise Eu-Jin Seow, prominent local architect and Professor of Architecture, notes that Coleman “had adapted the Palladian theme to tropical architecture” in his doctoral dissertation and Gretchen Mahbubani argues that “Coleman’s genius lay in skillfully adapting the Palladian manner to suit the tropical climate.”7

Hancock’s accounts are not unusual in that other architectural historians have also written about the “acclimatization” of classical architecture from the temperate metropole to the tropical colonies in their studies of the architectural history of other former colonies. In fact, Sten Nilsson, the pioneer architectural historian of colonial architecture in British India, even argues in European Architecture in India 1750–1850 that India’s tropical climate was in fact more congenial to classical architecture, which originated in the warm Mediterranean climate of Greece and Rome, than Britain’s northerly climes. Designed to exclude the powerful sun rays, rain, and provide shade in the Mediterranean climate, classical architectural devices such as shaded porticos, loggias and colonnades were, according to Nilsson, easily adapted to the Indian context.8 Hancock’s accounts are instead distinguished by his presentism and his insistence on seeing Coleman as a professional architect, as we shall see below.

In this chapter, Hancock’s accounts of Coleman are used as an entry point to foreground some of the historiographical problems of colonial architecture in Singapore and, more broadly, tropical architecture. Like Hancock, I am interested in origins, specifically, the origins of acclimatized or tropicalized colonial houses. This chapter focuses on the architectural history of early houses in Singapore built before 1870. Most of these were built for the Europeans, but wealthy locals also lived in such houses. Even though the processes described in this chapter did not end in 1870, it was chosen as an endpoint for a number of interconnected reasons. First of all, 1870 marks the end of the prevalence of an early type of colonial house that local architectural historian Lee Kip Lin characterized as square and compact, plain and unadorned, and largely symmetrical.9 The year 1870 was also shortly after two momentous events that accelerated colonial Singapore’s socio-economic development – Singapore, as a part of the Straits Settlements, became a crown colony and came under the direct rule of the Colonial Office in London in 1867, and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 which shortened the distance between Singapore and Europe. The year 1870 also roughly marked the arrival of professional architects and military engineers who were systematically trained in building construction. Most importantly, for the purpose of this genealogy, it was around 1870 that a systematic and explicit body of knowledge on how to build in the tropics emerged, as we shall see in Chapters 2 and 3. Unlike Hancock, however, I do not consider a building to be solely the outcome of the genius of the designer and trace the origins of early colonial architecture in Singapore to the metropole. Instead I explore what I call the heteronomous and heterogeneous conditions of architectural production. I end the chapter by exploring the types of early colonial house produced by multicultural influences and in relation to the preoccupation with comfort.

PRESENTISM AND HISTORIOGRAPHICAL PROBLEMS

A few years before Hancock published his first account on Coleman, his colleague at the PWD, Kenneth A. Brundle, published an important article on the change in climatic design principles from the prewar era to the postwar era. As an illustration of the change, Brundle criticizes the prewar Bungalow. He notes,

[T]here have been changes in planning technique, and post-war designs reveal a different approach to the problem of keeping the houses cool. The pre-war doctrine of “High Ceilings” preached by Health Officers and others appears to have influenced pre-war planners and never produced a really cool house. In this [prewar] example the height of the ceiling above first floor is sixteen feet, whereas the top of the highest ventilator is only eight feet. The trapping of enormous quantities of hot air is further assisted by the general shape and interior planning of the building, and one might be pardoned for wondering why the building has not “taken off” in the manner of Montgolfiers’ balloon which it so closely resemble in elevation.10

After dismissing the design of the prewar colonial bungalow (Figure 1.1), Brundle presents a few PWD postwar house designs (such as Figures 1.2 and 1.3) and argues that the postwar designs were based on better design strategies to facilitate cross-ventilation and sun-shading, and to provide for the comfort of their inhabitants. These strategies include the “one room thick” principle, i.e. the cross section of the building is only one room wide, the positioning of large windows and ventilators so that there would be no “dead air pockets”, and the proper orientation of the building with regard to the sun’s paths and prevailing wind directions. The strategies that Brundle proposes were based on the latest findings from building research carried out by the Colonial Liaison Unit (CLU), later the Tropical Building Division (TBD), of the Building Research Station (BRS) discussed in Chapter 5.

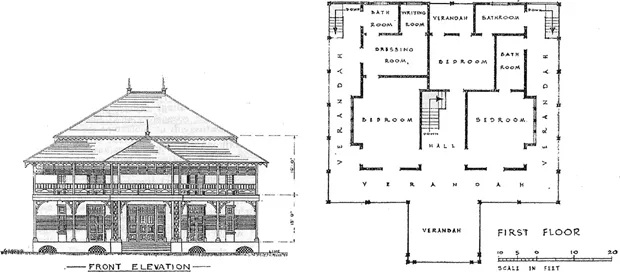

Figure 1.1

Elevation and first floor plan of a prewar colonial bungalow for senior officers, Goodwood Hill. Source: QJIAM 1 (2), 1951.

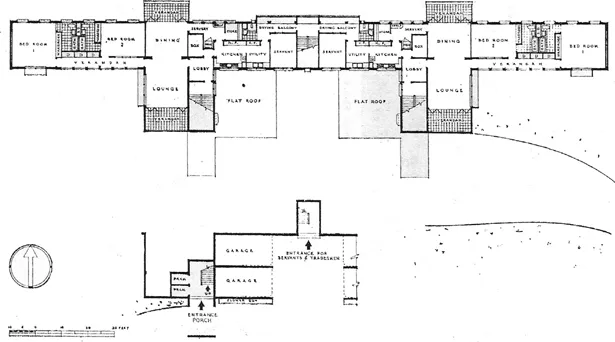

Figure 1.2

Sections of Nassim Hill Flats, an example of postwar apartments for senior officers. Source: QJIAM 1 (2), 1951.

Figure 1.3

Plans of Nassim Hill Flats, an example of postwar apartments for senior officers. Source: QJIAM 1 (2), 1951.

Although Brundle was referring to the typical colonial bungalow planned and designed by the Colonial PWD as an example of the prewar climatic design doctrine, he could very well be referring to the houses designed by Coleman. If we study two of Coleman’s best-known buildings – Maxwell House, completed in 1827 (Figure 1.4), and the house he built for himself, completed in 1829 (Figures 1.5–1.7) – we can notice the similarities with the colonial bungalow. Both the colonial bungalow and Coleman’s houses are compact with deep plans, which are certainly not “one room thick.” Furthermore, they are lofty and have “high ceilings” but definitely do not have openings or ventilators positioned just below their ceilings. Thus, they are bound to have “dead air pockets.” As a colleague of Brundle, Hancock would have been aware of the new climatic design doctrine. Moreover, Hancock singled out the senior government officers’ flats at Nassim Hill, used by Brundle to illustrate the new ...