eBook - ePub

Nehru

About this book

Judith Brown explores Nehru as a figure of power and provides an assessment of his leadership at the head of a newly independent India with no tradition of democratic politics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

A VOCATION TO POLITICS

. . .

THE WORLD OF INDIAN POLITICS IN THE LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY

Nehru was born in 1889, an Indian baby but a citizen of the British empire and a colonial subject of Queen Victoria. This was a time before imperial rulers suffered serious self-doubt about their role, a time when Britain seemed quite evidently the strongest world power. Yet British rule in India, the raj,1 was a comparatively recent phenomenon in the time-scale of India’s own history. Recorded civilisation on the subcontinent stretched back over 4000 years; and in the more recent past India had developed sophisticated state-systems in the form of empires and small regional states at least contemporary with the emerging states of early modern Europe. When English traders first ventured into Indian waters and settled in tiny numbers in small coastal ‘factories’ in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries they operated on Asian terms, as one of many international groups involved in the spice and textile trades. Only in the later eighteenth century did the men of the East India Company begin to exercise political control, by acquiring from Indians rights to gather land revenue. This revenue became the financial foundation of an increasingly powerful EIC government, backed by a large standing army, which controlled the whole subcontinent by the 1820s. The upheavals across north India in 1857 brought to an end Company raj, and India came directly under the control of the British Crown and parliament. (The great Indian territorial sway of the British sovereign was recorded in Latin on British domestic coinage until 1947.)

However, British politicians and parliamentarians were not in any simple sense land-hungry, despite the vast areas which came to be coloured pink on political maps of the world. Their preference was for less expensive means of furthering British interests globally, and they were deeply suspicious of direct governance in places where there was no large-scale white settlement. But when Nehru was born virtually all British opinion was agreed that the raj was an inescapable fact of British life, a special case for direct imperial control because it was uniquely vital to Britain’s world-wide position. A century later the importance of India to Britain is less easy to comprehend. India was the home of the Indian army, a huge imperial reserve of fighting power numbering well over 100,000 Indian troops, paid for by Indian tax-payers. It was often deployed in many different parts of the empire for imperial purposes as well as defending India’s own borders, particularly the north-western land frontier, the ‘back gate’ of imperial Russia. India was also highly significant for British trade and investment. Towards the end of the century nearly one-fifth of British overseas investment was in India. The subcontinent was the largest single market for British exports, mostly manufactured goods ranging from soap, books and textiles to railway locomotives and carriages. India exported raw materials such as cotton and jute, and of course tea, to Britain, Europe, North America and South-East Asia, not only supplying British domestic needs but also by exporting to other areas helping Britain to balance her trading books world-wide. India’s public finance and the exchange rate of the rupee were managed in the imperial interest, thus supporting sterling as a strong international currency. Beyond this, in more personal terms, India also provided a small but significant area for the employment of expatriates, mostly from Britain’s professional classes, in her administration, army, police, forestry and medical services, education, and in the Christian church, as chaplains and missionaries. Early in the twentieth century there were about 150,000 Europeans in India, of whom over one-third were women. Few of these were permanent settlers, because of the climate and the nature of their work: most returned to live out their old age in Britain in modest comfort.

Despite the centrality of the raj to Britain’s world position, the British were essentially pragmatic imperialists, in India as elsewhere, and were remarkably silent on the ideology underpinning their imperial enterprise.2 Perhaps ‘ideology’ is itself too strong a word, presupposing a coherent, articulated system of ideas. More accurately most British people concerned with India would have agreed on certain assumptions, often unvoiced, about India, Indians and the nature of their own dominion. It was assumed that the raj was virtually permanent. Even in 1912 Lord Hardinge, as viceroy, was writing that there was ‘no question as to the permanence of British rule’ and that the idea of colonial self-government for India, as in the White Dominions, ‘must be absolutely ruled out’. He dismissed the notion as ‘ridiculous and absurd’.3 Echoing through such protestations was the assumption, too, that British rule was morally defensible for a people who were Christian and democratic, despite the apparent contradictions between what they found acceptable ‘at home’ and in India. British belief in the morality and legitimacy of their raj rested on their vision of Indians and ‘Indianness’ as compared to their own assumed qualities of character. Such a perception, which historians have labelled ‘Orientalism’, saw Indians as profoundly different in character as well as historical experience. They were seen as weak and effeminate, corrupt and unreliable, hopelessly divided among themselves by religion and by the Hindu caste system, symptom of a society in decay, waiting to be revivified by good government, economic advance and sound religion. Consequently British rule was in British eyes a providential imposition, ‘good’ for India’s peoples. It would provide sound government and just laws in place of chaos or despotic rule; and it would provide an environment for the slow processes of educational advance and social reform. It would also prevent Indians from exploiting or fighting each other. Thus armed with a good conscience, generations of men (and the women who went as wives and missionaries), often from the same small group of ‘Anglo-Indian’ families, committed themselves to ‘service’ in India.

Yet it would be wrong to impute too much power and influence to the raj. Despite its panoply of civil and military power, the British never had the financial or expatriate manpower resources to run an efficiently authoritarian state. They could threaten and punish: but they relied essentially on the cooperation or at least acquiescence of Indians in and with their regime. Further, they had little real control over the deeper forces in Indian society and economy. Yet the British presence, their structures of rule, and their Orientalist assumptions about India and its peoples were the context in which Indians in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries lived, worked, prayed and played, and thought about life. The political and administrative structures of the raj, moreover, laid down the ground-rules for Indian political organisation and behaviour. They provided some of the foundations for the new nation state Nehru was to help create, but which Hardinge had found impossible to envisage when Nehru was a young man.

The enterprise of imperial governance

To understand the nature of imperial governance it is important to recognise the sheer size of the operation. The British had to attempt to understand and control a subcontinent infinitely greater and more diverse than their own islands. Nor did they have in the later nineteenth century any of the tools modern governments have at their disposal, such as swift communications, propaganda techniques or scientific methods of measuring social and economic forces. The area under the raj was 1,800,000 square miles, more than twenty times the area of Britain, and equivalent to continental Europe without Russia. Further, the subcontinent was even more varied than contemporary Europe. Within it there were major regions, such as Bengal, Madras or the northern plains, each distinguished by climate, crops, food, clothes, culture and language. There were also several distinctive religious traditions unequally represented across India. Hindus formed a majority of over two-thirds throughout the country, but a large Muslim minority was heavily represented in the north-west and in Bengal, owing its origins in part to the presence in earlier centuries of a Muslim empire over much of the subcontinent, following invasions of Muslims from the north-west. There were smaller groups of Sikhs, Parsis and Christians, and tribal groups who were often geographically isolated and barely touched by any of the world’s organised religious traditions. The British perceived many of these distinctions between Indians, particularly those of religion and caste, as uniquely powerful and divisive in Indians’ psyche and society, as central to ‘being Indian’, and therefore as evidence that Indians were incapable of modern national sentiment and organisation, let alone democratic practice. Later historians may discard such Orientalist justification of imperial rule. But the size and diversity of India has remained a critical issue for effective and acceptable governance on the subcontinent, as Nehru was to discover as he endeavoured to establish government on popular consent.

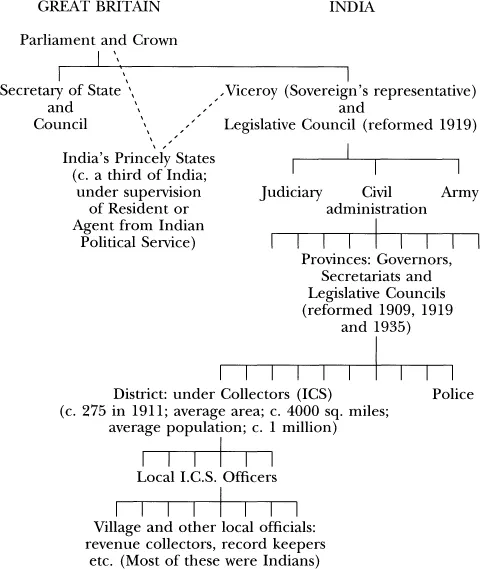

British imperial rulers, like the Indian rulers they replaced, were less interested in articulated consent. They saw Indians as subjects rather than participatory citizens and recognised that coercive power lay at the heart of their rule, buttressed by the operation of the rulers’ prestige, a facet of government over which they took extraordinary care. By the later nineteenth century they had evolved a structure of government subject ultimately to parliament in London (see Figure 1). One-third of India stayed in the control of the remaining Indian princes, subordinate allies left in place as a reward for loyalty during the turmoil of 1857. In the remaining two-thirds, ‘British India’, the lines of civil and police power flowed down from the viceroy or sovereign’s representative, through the provinces into which India was divided, some being equal in area to Britain itself. The raj’s main local representative was the district officer, who was magistrate, collector of revenue, the man with clout who could get things done and whose path it was unwise to cross. He often controlled an area as large as an English county. This autocratic style of government was buttressed, and somewhat tempered, by the creation and gradual expansion of consultative councils for the viceroy and provincial governors, whose members were part nominated and part elected, to represent what the British saw as significant ‘interests’ in Indian public life, such as large landholders, universities or in certain areas business associations. Simultaneously Indian cooperation had been sought in the running of local government – in town councils and district boards, as an exercise in political education and in cheaper administration. The whole edifice was designed for essentially static, conservative governance, its goals being tax collection and social and political stability. The role of government was assumed to be limited (as in contemporary Britain, of course) and there was very litle human investment in such areas as education, health and social welfare. Only about 4 per cent of government expenditure went into such areas, less than in the princely states, and much less than in Britain itself.

Figure 1 The structure of imperial government in India

What roles were there for Indians in this regime, what routes to power in India’s public life? In the formal business of imperial security and civil administration Indians outside princely territory had a severely limited role except in very subordinate positions. The army’s officer corps and senior police ranks were expatriate preserves. Despite a royal pledge in 1858 of equality among imperial subjects, in practice even the few Indians qualified by western education to attempt entry into the prestigious Indian Civil Service (ICS) found it difficult because of practical barriers such as the young age required of candidates for the entrance examination, and the fact that for many years it could only be taken in London. By 1909 only about sixty out of 1142 ICS officers were Indian. By contrast the lower ranks of the army, police and civil government were filled entirely by Indians. More informally, Indians of substantial social standing, ‘native gentlemen’ such as landholders, business men and some of the western educated who had risen to new status and wealth through the professions of law, medicine and education, were co-opted into the enterprise of imperial government through the consultative councils and local self-government institutions, and through the durbari system of open access (particularly for notable people) to the representatives of empire. At the base of the raj district officers, for example, kept their own local durbar lists, and ranked their trusted locals in strict precedence for public gatherings: their names were also recorded in the handing-over notes when officers left the district. At the highest levels invitations to viceregal and royal durbars and indeed the imperial honours system displayed the value of a range of notable Indians to their rulers and the routes through which they could achieve a certain standing in the eyes of the raj and of their countrymen.

Although the official British in India were prepared to welcome certain types of high-born or gentlemanly Indian into their structures and formal functions, and had a high regard for those they categorised as ‘martial races’, the raj as seen and experienced by most Indians was clearly and sometimes crudely racial. Lord Curzon as viceroy at the turn of the century forcefully condemned this aspect of the British presence despite his contempt for educated Indians. British attitudes of racial superiority and separation had become increasingly strident during the nineteenth century, particularly after the 1857 mutiny. They were never enshrined in legislation, but British social conventions made their assumptions abundantly clear, in ways which were deeply offensive, particularly to western-educated Indians.4 They tended to live apart from Indians in urban areas, their large homes in elegant gardens safely built on broad well-maintained roads away from ‘black town’. In the districts the bungalow, with its size and structure, its grounds and servants’ quarters, marked out the European home. Here British people created a conservative version of upper-middle-class life ‘at home’, which was itself profoundly stratified, where every family knew its place in relation to others in the imperial hierarchy. Its conventions, manners and morals were strictly policed by the memsahib, or European wife, to maintain a clear distinction between the domestic lives of rulers and their subjects, and of course to prevent any sexual intimacy between the two races. Europeans also took their recreation apart from their subjects, in their clubs, and in the ‘hill stations’ such as Simla where they attempted to reconstruct versions of an English rural idyll in a cooler climate. Informal and easy social relations between Indians and the British were hazardous and fraught with potential for misunderstanding, even where they were sought. It was hardly surprising that British officials felt most at ease in the role of paternal patron, in the company of those they saw as simple rural folk and the heart of ‘real’ India.

Social and economic change

Another element in the European image of India was a supposed conservatism which locked people into social relations dictated by tradition and prevented social mobility or economic innovation. Historical research has recently shown how wrong it is to characterise Indian society and economy as ‘unchanging’; and also how the British themselves helped to construct and solidify ‘tradition’ in their attempts to enquire into and describe the society over which they now ruled. Yet it was true that India had not experienced the radical upheavals in the economy and in social organisation produced in parts of the western world by the processes of large-scale industrialisation and later by the growth of the professions. The nature of Indian society and its economic foundations thus had profound implications for the nature of politics on the subcontinent, and in particular framed the world of Indians who in new ways began to speak for ‘India’ and to organise a new style of ‘national’ politics.

In the 1890s India’s population was in the region of 300 millions. The numbers were severely restrained by the lack of modern medicine and awareness of public hygiene among the vast majority, which in the later twentieth century were dramatically to reduce infant and maternal mortality, and to control such killer diseases as smallpox, cholera, plague and malaria. Poverty, leading to malnutrition, often made women, the old and very young particularly vulnerable: and wide-scale famine was still a real threat to life in some areas. Life expectancy at birth was under twenty-five years. Yet in the last quarter of the century forces were working to change the life experience of all Indians in ways unimaginable to their parents. For their own purposes of security and government the British began to draw India together into a new geographical and political unity with a web of reinforcing ties – particularly by their common administrative institutions and by new means of communications. The latter included metalled roads, railways and the telegraph and postal services, all of which linked areas once separate or isolated. People, goods, news and ideas began to flow more freely across the subcontinent. Moreover, in English, the new language of government and higher education, educated Indians had a common means of communication which came to be more widespread even than Hindustani, the trans-Indian language which had evolve...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 A Vocation to Politics

- CHAPTER 2 Apprentice to Power: Gandhi’s Heir, 1923–c. 1945

- CHAPTER 3 The Transfer of Power: Tryst with Destiny’

- CHAPTER 4 The Visionary as Prime Minister

- CHAPTER 5 The Limits of Power

- Conclusion

- Bibliographical Essay

- Chronology

- Glossary

- Maps

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Nehru by Judith M. Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.