- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Illustrates how maps tell us as much about the people and the powers which create them, as about the places they show. Presents historical and contemporary evidence of how the human urge to describe, understand and control the world is presented through the medium of mapping, together with the individual and environmental constraints of the creator of the map.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mapping by Daniel Dorling,David Fairbairn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Naturwissenschaften & Geographie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

NaturwissenschaftenSubtopic

GeographieChapter 1

The history of cartography

An introduction to early maps

The Introduction to this book suggested that different peoples and societies can have very different perceptions of the world, and that there exist, therefore, a variety of ways of interpreting and mapping it. If maps result from such interpretations, they too will vary, and reflect their makers’ ‘world-views’. Imbued with meaning, inference and prejudice, both conscious and subconscious, it is clear that maps are not simple representations of reality. The most effective way of understanding this is to study ancient maps, including map-like objects, looking, as far as we can now determine, at what their creators chose to show, how it was shown and what embellishments were made on the map face. The world-views that are reflected in contemporaneous map production vary from one cartographer to another and from one culture to another. Throughout history, personal and societal influences have been as strong as the shape of the landscape in determining the appearance and content of maps.

Virtually all early map products attempted to represent impressions of the landscape. In many cases the ‘andscape’ of the earth was placed in its assumed position in the cosmos: many maps were (and many still are) representations of theories and views of the universe. Alternatively, early cartographers often attempted to portray a view of the entire earth as they saw it, concentrating on the distribution and relationships of known or imagined features within the bounds of the planet. Such small-scale map products were balanced by occasional large-scale representations which covered considerably smaller tracts of landscape and which were created for more specific purposes, such as navigation or social regulation.

It must be appreciated that the study of such maps can encompass an enormously long time period (the earliest surviving map artefacts date from 3500 BC, although prehistoric rock art, some of which may have ‘proto-cartographic’ features, dates back to the Palaeolithic period of 30 000 BC) and embraces a vast range of cultures and societies, each with its own ideas about how its world-view could be represented in map form. Differing cultures had differing inclinations to produce such varying maps. Prehistoric peoples lived closer to nature, were dependent upon it and often relied on mobility to follow a hunter—gatherer style of life. Their innate capacity to create a coherent reference framework from the natural surroundings (‘spatialization’), their well-developed sense of vision and the sketching ability demonstrated in the cave paintings which still exist, led in the majority of cases to the development of map-making as a means of communicating and recording information. Later, more settled societies used local maps for inventory and management, but still produced maps based on world-views for displaying the place and nature of the earth.

The human mind and the shape of the earth: reconciling interpretation and reality

In many societies there were irreconcilable differences in the world-view shown by maps produced by and for the philosopher or thinker, and those of the traveller or scientist. Variation between cultures has also been apparent, even at similar time periods in history. For example, the significantly different traditions emanating from Greece and from Rome during a common period in the two centuries around the time of Christ show the wider intellectual view of the Greeks contrasted with the more practical measurement-based cartography of the Romans. The former was much influenced by philosophical reflection, but also by astronomical observation, and resulted in often speculative world maps (see p. 9). The latter took a considerably more structured technological approach to the measurement of distance and angles on the ground, to allow for the creation of large-scale land ownership maps and route diagrams. Roman maps depicting the entire world were rare (Figure 1.2) and displayed a limited perception of areas beyond their own, measurable, realm.

Such variation reveals that the development of map-making has often been fitful: there are enormous historical gaps in any perceived ‘progression’ and many societies felt perfectly able to function without any formal map-making output at all. It is thus difficult to put forward a coherent, generalized view of the history of cartography (see Box 1.1 for an outline of the paradigms within which the subject can be studied). However, it can be suggested that, prior to the period characterized as ‘The Age of Discovery’ (starting about AD 1490), world and cosmos maps tended to be generalist, philosophical interpretations of religious and superstitious belief whilst local maps were much more practical, used for land appropriation or management and other specific purposes. From the turn of the sixteenth century, a more enlightened approach to cartography was apparent as observation and measurement became the foundations of map-making, although at certain previous times, within Chinese cultures in particular, such practices were prominent. It should be recognized that this more ‘scientific’ view of the mapping process was, and still is, tempered by the prevalent ideology of the map-maker, who is able to manipulate the appearance and content of the map to a surprisingly large degree. The reconciliation of an interpretation of reality (and its subsequent representation in map form) with reality itself may be satisfactorily carried out only for some map users and some map-use tasks, not for all: maps are not mirrors of reality and the mind of their creators is imprinted on every map.

Box 1.1 Contemporary mapping box – Methods of studying the history of cartography

There are certain approaches that can be made in the study of the history of cartography, ranging from that of the ‘interested amateur’, who might be inclined to visit book fairs and antique shops in the hope of discovering a valuable old document, to the analytical study of the serious historian, who may try to rationalize the appearance and content of a map by detailing the various factors that affected the mapping and map-making processes.

There is a distinctively cartographic viewpoint which combines a study of the map documents, the technologies which allowed their creation, and an appreciation of the context within which mapping activity developed. Within this approach there are a number of different ‘paradigms’ or frameworks of study:

• The ‘Darwinian’ view: map-making improves as civilization progresses, and knowledge of spatial data moves ‘from myth to map’. Here, in particular, accuracy is examined – accuracy of geodetic and planimetric systems, and also of content and representation.

• The ‘old is beautiful’ view: most cartographic research has been undertaken on older maps. Maps from the Renaissance have been studied much more fully than those of the early twentieth century, for example.

• The ‘nationalistic’ view: concentrating on the map production in one area or one nation state is also seen as a valid way of following the development of map-making.

Although accuracy is a prime measurable indicator of ‘progress’ in map-making, there are other map elements which can be considered:

• the narrow meaning of maps and their graphical rendering – their use as documents to communicate specific messages to the reader;

• the use of maps in a wider societal context, in particular as tools of oppression, governance, policy-making and regulation;

• the intellectual endeavour required to create and reproduce maps, looking at mapping from viewpoints as diverse as psychological investigations into ancient views of the earth and the history of the technology required to print and disseminate maps;

• the artistic representation on the map face, reflecting on the map as a decorative objet d’art or an adjunct to artistic output.

The relationship of mapping to other human activities

The history of cartography has usually been written from a chronological perspective (see Further reading) often within the ‘Darwinian’ paradigm described in Box 1.1. This chapter, however, selectively considers periods in the history of cartography which exemplify the connections between map-making and other societal activities. The propensity to map is a function of such activities, which include the accumulation of spatial data (from philosophical insight, religious belief and scientific observation), the recognition of the utility of spatial representation (in navigation, education, land management, and for political ends) and the ability to create map products (using contemporary technology).

It is important to note also that this chapter, along with most other works on the history of cartography, does tend to take a Eurocentric view of the history of cartography. This reflects the rich inheritance of surviving map artefacts from western cultures which has tended to dominate the interest of historians of cartography, and occurs despite the numerous encounters by western explorers and map-makers with indigenous peoples which have given insight into the mapping urges of others. There has been, at certain stages of history, an evident lack of map-making activity in some societies outside the ‘western’ realm (as well as within it), but this may not imply a lack of mapping ability. Indeed, mapping ability (as distinct from map-making) seems innate in every culture.

Philosophy and its influence on mapping

Speculation on the place of the earth within a cosmic framework was one of the most important roles for early philosophers. These views developed in those ancient civilizations with sufficient specialization of labour to allow for the establishment of groups of such scholars. The world-views propounded by them varied enormously, viewing the earth as, for example, a square (early Chinese philosophy in the Han dynasty up to the second century BC), as one of a number of concentric rings around an unspecified globe (the Cakravala system, Buddhist inspired, in the sixth century AD), a disk floating on the back of a fish (Ainu belief in northern Japan), one of a number of flat platforms, which also included the underworld, connected by staircases (intermittent Babylonian philosophy), a labyrinth (a widespread, cross-cultural schema, including parts of India), the shape of tree (Scandinavian mythology) or as a globe (Greek philosophy of Anaximander (approximately 610–546 BC)). In all cases, the philosophical contemplations were unaffected by any direct observation of the earth; but such world-views fulfilled their purpose in explaining and propagating particular myths, in encouraging further investigation into the nature of the environment and in promoting a search for order and understanding.

Greek philosophy 550 BC to AD 150

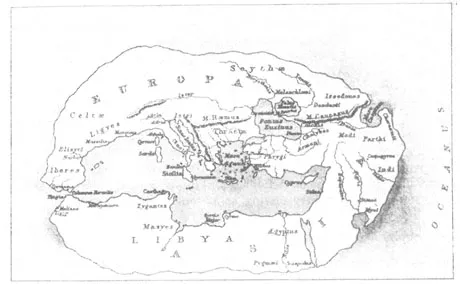

The spherical nature of the earth was readily accepted by Greek philosophers by 550 BC. The pre-eminent school was that of Pythagoras (active in 530 BC), for whom the geometric perfection of the sphere was sufficient proof of its suitability as a framework for explaining the earth. The bounded and regular nature of the globe led to an over-optimistic opinion by such scholars that their current description of the earth was complete, or at least predictable. As Greek cartography moved towards a greater reliance on observation and measurement, shortcomings became apparent. Herodotus (489–425 BC) was among the first to propose a more empirical approach, relying on exploration and travel instead of pure geometry (in its modern sense) alone. Figure 1.1 shows the world map (about 500 BC) of his immediate predecessor, a major Greek historical and geographical writer, Hecataeus.

Figure 1.1 Map of Hecataeus (about 500 BC).

Map use in Ancient Greece was widespread and many episodes in Greek literature describe the everyday application of maps in law, travel and military campaigns. Despite the theoretical nature of much mapping, the educated populace was familiar with such documents. Later philosophers, e.g. Aristotle (384–322 BC), successfully married the concepts of Pythagoras with the pragmatism of Herodotus. The spherical nature of the earth was confirmed through observation of eclipses (the circular shadow of the earth on the moon, for example), recognition of the circumpolar motion of the stars and knowledge that the (northern hemisphere) Pole Star changed its angle of elevation with change in latitude. Information regarding the perceived inhabitable and inhospitable zones of the earth was incorporated by Aristotle, along with his description of a ‘system of winds’, to give a philosophically coherent and balanced world-view, sufficient to serve the Eastern Mediterranean culture of the period from the sixth century bc to the culmination of Greek cartography with Ptolemy (see Box 1.2) during the second century AD.

Religion and its influence on mapping

Well before the philosophical musings of early civilizations, which were based on the rationality and logic of those times, early societies invoked superstition and supernatural beliefs in attempting to explain the nature of the earth and expound a world-view. The development of organized religion was, according to one’s opinion, a logical progression of such behaviour or an enlightened response to its deviance. Religious belief has had an enormous impact on the development of civilizations throughout all parts of the earth and everyday activity in many societies has been, and is still today, governed by behavioural codes

Box 1.2 Personality box – Ptolemy and the scientific nature of Greek cartography

Claudius Ptolemy (approximately AD 90–168) was unique in playing a role as the distinctive cartographic thinker and practitioner of two markedly different periods in European history, separated by over 1300 years. In the interim his writings were of value to map-makers of other cultures, notably Islamic and Byzantine civilizations east of Europe. His life’s work, emanating from his home in Alexandria (site of the pre-eminent library of the age) in the second century AD, is considered to be the culmination of Greek map-making practice, and for a period in the fifteenth century AD translations of his work, from Byzantine copies (in Greek) into the Latin idiom, were regarded in western Mediterranean and north European societies as the complete source of geographical knowledge.

Ptolemy’s writings on cartography cover instructions on map-making, discussions on the nature of map scale, mathematical descriptions of map projections and gazetteers of known geographical features. It is debatable whether Ptolemy himself produced the complete compendium of his cartographic work, the eight-volume work Geographia, but it forms the summary of his contribution to map-making. Geographia started with comments on the cartography of the day, personified by his near-contemporary, Marinus of Tyre. Marinus’ cartography was criticized by Ptolemy: by not making good use of astronomical observation Marinus had overestimated the size of the inhabited world (oecumene in Gree...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The history of cartography

- Chapter 2 The shape and content of maps

- Chapter 3 Navigation, maps and accuracy

- Chapter 4 Representing others

- Chapter 5 Mapping territory

- Chapter 6 New scales, new viewpoints

- Chapter 7 Geographical information systems

- Chapter 8 Alternative views

- Chapter 9 Representing the future and the future of representation

- References

- Index