eBook - ePub

Methods of Heuristics

- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Methods of Heuristics

About this book

This volume constitutes the edited proceedings of an interdisciplinary symposium on Methods of Heuristics, which was held at the University of Bern, Switzerland, from September 15 to 19, 1980. In organizing the symposium, the editors of the present volume were able to invite specialists from psychology, computer science, and mathematics. From their own perspective they made contributions to the central questions of the conference: What are heuristics, the methods and rules guiding discovery and problem solving in a variety of different fields? How did they develop in individual human beings and in the history of science? Is it possible to arrive at a commonly accepted definition of heuristics as the field unifying all these efforts, and, if yes, what are its basic characteristics?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Methods of Heuristics by R. Groner, M. Groner, W. F. Bischof, R. Groner,M. Groner,W. F. Bischof in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Clinical Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Approaches to Heuristics: A Historical Review

University of Bern, Switzerland

Nowadays the main usage of the word “heuristic” is mostly the adjective in the sense of “guiding discovery” or “improving problem solving.” There might also be a slightly negative meaning attached to it of a less than perfect method or a lack of solution guarantee. The modern picture of a search for the solution, which might be intelligently directed but still has its inherent uncertainty, leads to its origin in ancient Greece where the verb “heuriskein” means to find. In the history of science we find attempts to formulate methods for finding proofs and for arriving at new discoveries. They belong to what was sometimes called the art of discovery, or later, heuristics.

FIRST METHODS: ANALYSIS AND SYNTHESIS

At all times, in all fields, methods that have grown out of experience are employed to deal with problems. One of the first fields where such methods were not only applied but explicitly stated was geometry in ancient Greece. The Greek mathematicians were mainly concerned with two kinds of problems, constructing geometrical figures from given data and finding proofs of theorems in geometry. They used two ways to find a solution: They began by assuming the problem solved and worked from there until they reached a point that was already known or proved to be true, or they started from the admitted body of mathematical knowledge and worked towards the desired result. The first method was called analysis, the second synthesis.

The invention of the method of analysis was attributed to Plato by Proclus, but modern historians of mathematics (Hankel, 1874; Heath, 1921) think that it was already used by the Pythagoreans in the 6th century B.C. They suggest that Plato was probably the first to become clearly aware of this procedure as a scientific method.

The oldest definitions of the two methods we know of are contained in Book XIII of Euclid’s Elements (edited by Heath, 1926): “Analysis is the assumption of that which is sought as if it were admitted < and the arrival > by means of its consequences as something admitted to be true. Synthesis is an assumption of that which is admitted < and the arrival > by means of its consequences at the end or attainment of what is sought [Vol III, p. 442].”

These definitions are followed by analysis and synthesis of five propositions. To clarify the application of these methods the analysis and the synthesis of the first proposition are given as an example. The first proposition concerns the golden section:

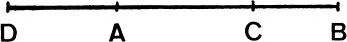

Let AB be divided in extreme and mean ratio at C, AC being the greater segment, and let AD = 1/2 AB. I say that (sq. on CD) = 5 (sq. on AD).

FIG 1.1.

(Analysis.)

For since (sq. on CD) = 5 (sq. on AD), and (sq. on CD) = (sq. on CA) + (sq. on AD) + 2 (rect. CA, AD), therefore (sq. on CA) + 2 (rect. CA, AD) = 4 (sq. on AD).

For since (sq. on CD) = 5 (sq. on AD), and (sq. on CD) = (sq. on CA) + (sq. on AD) + 2 (rect. CA, AD), therefore (sq. on CA) + 2 (rect. CA, AD) = 4 (sq. on AD).

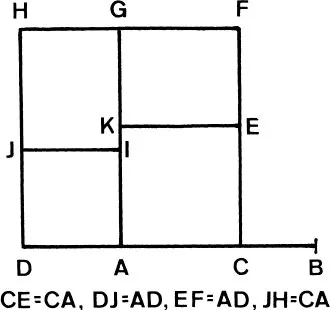

FIG 1.2.

But (rect. BA, AC) = 2 (rect. CA, AD), and (sq. on CA) = rect. (AB, BC)1). Therefore (rect. BA, AC) + rect. (AB, BC) = 4 (sq. on AD), or (sq. on AB) = 4 (sq. on AD): and this is true, since AD = ½ AB.

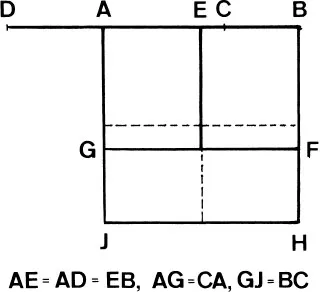

FIG 1.3.

(Synthesis.)

Since (sq. on AB) = 4 (sq. on AD), and (sq. on AB) = (rect. BA, AC) + (rect. AB, BC), therefore 4 (sq. on AD) = 2 (rect. DA, AC) + (sq. on AC). Adding to each the square on AD, we have (sq. on CD) = 5 (sq. on AD) [Vol. III, p. 442 f.], (Fig 1.2 and Fig 1.3 are added).

Since (sq. on AB) = 4 (sq. on AD), and (sq. on AB) = (rect. BA, AC) + (rect. AB, BC), therefore 4 (sq. on AD) = 2 (rect. DA, AC) + (sq. on AC). Adding to each the square on AD, we have (sq. on CD) = 5 (sq. on AD) [Vol. III, p. 442 f.], (Fig 1.2 and Fig 1.3 are added).

Examples of analysis are rare in the Greek mathematical literature, and they are always followed by a synthesis which is just the converse of the analysis. In most cases only the synthesis is reported. It was much more important to convey to the reader that the newly discovered results could be derived with logical rigor from the recognized body of mathematical knowledge than to show how they had been found. The development of the art of demonstration was one of the greatest achievements of ancient Greek mathematics. However, from the point of view of heuristics, it would be fortunate if the communication of mathematical results, up to date, included more remarks about their discovery.

The example from Euclid’s Elements shows how the method of analysis was applied. First, the desired result, say theorem A, was assumed to be true. Then from A another theorem, C1, was derived. From C1, C2 was derived, and so on until theorem Cn was derived, which was already known to be true. Now, theorem A is only true if every step in the chain is convertible, that is Cn–1 has to be proved a necessary condition of Cn, Cn–2 a necessary condition of Cn–1, and so on up to A. This was achieved by the subsequent synthesis.

The method of analysis can also be applied in a different way. Assuming the theorem A to be true, instead of working forward from A over a chain of consequences, it is possible to work backwards from A over a chain of “causes,” that is, a theorem C1 implying A has to be found, then a theorem C2 implying C1 and so on until an already proved theorem Cn is reached. A description of the method of analysis given by Pappus suggests that the Greek mathematicians used it both ways. Pappus states (quoted from Heath, 1926):

Analysis then takes that which is sought as if it were admitted and passes from it through its successive consequences to something which is admitted as the result of synthesis: for in analysis we assume that which is sought as if it were [already] done [γεγovóζ], and we inquire what it is from which this results, and again what is the antecedent cause of the latter, and so on, until by so retracing our steps we come upon something already known or belonging to the class of first principles, and such a method we call analysis as being solution backwards [ἀvάπαλιv λvσιv] [Vol. I, p. 138].

Pappus lived around the year 300 in Alexandria, the same place Euclid had lived about 600 years before. He wrote comments and additions to the classical works of mathematics. The first statement in his definition of analysis looks like a quotation from Book XIII of Euclid’s Elements. The second statement however describes the working backward over a chain of sufficient conditions. Given a problem, whether to work backward or forward from the hypothetical solution probably depends on how easily the problem solver has access to the antecedent parts or to the consequence parts of the rules he needs to transform the assumed solution into something known.

Pappus distinguishes between two kinds of analysis, theoretical analysis and problematical analysis (Heath, 1926, Vol. I, p. 138 f.). Theoretical analysis is concerned with finding proofs. From a theorem A that has to be proved, other theorems are successively derived until a known theorem B is reached. If B is false, A is false too. If B is true, then it has to be checked whether every step in the chain is convertible in order for A to be true. We notice that the method of indirect proof or reductio ad absurdum is a variety of theoretical analysis. Problematical analysis is concerned with searching for a geometrical object satisfying certain conditions. This is the problem of constructing a certain figure from given data. The conditions are assumed to be satisfied and are then transformed until they become related to the given data such that it is possible to construct the figure.

The methods of analysis and synthesis appear later in almost every treatise on problem-solving methods. They are not restricted anymore to the field of mathematics alone, but they are considered general methods applicable to any problem.

THE SEARCH FOR ALGORITHMS

Later on, the history of heuristics can be best characterized as a search for algorithms. Algorithms are step-by-step procedures that “mechanically” produce a solution to any problem out of a certain class of problems. Simple examples are Euclid’s algorithm to determine the greatest common factor of two integers or the algorithm to determine the inverse of a matrix.

The term algorithm can be traced back to the name of a mathematician, Mohammed ben Musa al Khovarezmi, who lived around the year 830 at the court of the caliph al Mamum at Baghdad. He had written a book on rules of arithmetic developed by the Indians. In the Middle Ages it was translated into Latin under the name “Algoritmi de numero Indorum.” Later, “algoritmi” or “algorismi” was considered a Latin possessive case, and “liber algoritmi” was used as a title for books on arithmetic. Finally, when the origin of the word must have been forgotten completely, it was mistaken for a Greek word and the spelling was changed into “algorithmi” (Hankel, 1874).

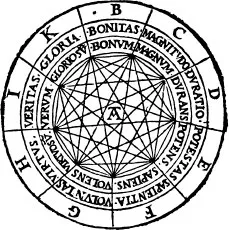

The successful algorithmic methods in arithmetic and algebra stimulated Raimundus Lullus, a Spanish philosopher of the 13th century, to search for a general algorithm that would produce every truth. In his famous work Ars Magna (1656) he described a system where you start with a few classes of basic notions and by combining them in a systematic way you should invent everything. Lullus even invented a mechanical device to generate all combinations. He wrote the six classes, each containing nine concepts, on six concentric discs. Now by turning the discs against each other he could have arrived at every possible combination.

Lullus did not know combinatorics and probably underestimated the number of combinations his exhaustive search algorithm would generate, because he also thought of exploring all combinations of all pairs of basic concepts that would amount to 2’176’782’336 cases. His work is not interesting from a mathematical point of view, but it had a great influence.

Descartes, too, believed that algorithms would eventually be found for all mathematical problems, perhaps also for the philosophical ones. He developed analytic geometry to transform geometrical problems into algebraic ones that can then be treated by algorithmic procedures. Changing the representation of a problem can be a way of solving it. To study the role such representational shifts play in the process of problem solving is an important part of the field of heuristics.

Descartes (1908) recommended in his 21 heuristic rules to direct the mind (“regulae ad directionem ingenii”) to reduce every problem, if possible, to algebraic equations. In particular, the rules say that one should first reduce a problem to its simplest form omitting all superfluous information. One should try to quantify the problem in geometrical terms, drawing figures. One should determine the known and unknown magnitudes. Then, one should dissect the conditions that the unknowns have to satisfy in as many parts as there are unknowns in order to get as many equations, and finally one should reduce all equations to one. Solving a problem by means of algebraic equations is an example of the application of the method of analysis.

FIG 1.4. One of the six discs of Lullus’s device

Descartes’s remaining rules are more of a psychological nature and are concerned with the optimal functioning of the human mind. They recommend to study a problem as long as it is necessary to understand it clearly, to use the senses, the imagination and the memory, to support the memory using external representations of the problem, and to practise the mind solving a lot of problems that have already been solved by others.

Leibniz critized Descartes, saying that he had given us beautiful rules but no means to execute them. The rules were too general to be of any use. He (Leibniz, 1880) even put his criticism into a sharp satirical form, summarizing Descartes’s rules in the following statement: “Sume quod debes et operare ut debes, et habebis quod optas [Vol. IV, p. 329].” (“Take what you have to take, and work the way you have to, and you will get what you are looking for.”)

Leibniz himself took the greatest effort in searching for a general method that would solve every problem in an algorithmic way. In his youth, when he was studying geometry and algebra, the idea came to him that it should be possible to find a relatively small set of primitive concepts from which all known concepts and new ones could be derived (Couturat, 1961b). Later, in his dissertation “De arte combinatoria,” he worked out his plan. All notions should be decomposed into a few, simple, independent and noncontradictory elements. He called them “alphabet of human thoughts.” These elements should be represented by appropriate symbols. Combining them in a systematic way would then lead to all known notions and also generate new ones. Leibniz (1880) writes about his method in a letter to the duke of Braunschweig-Lüneburg:

In Philosophia habe ich ein Mittel gefunden, dasjenige, was Cartesius und andere par Algebram et Analysin in Arithmetica et Geometria gethan, in allen scientien zu wege zu bringen per Artem Combinatoriam, welche Lullus und Pater Kircher zwar excolirt, bey weiten aber in solche deren intima nicht gesehen. Dadurch alle Notiones compositae der ganzen welt in wenig simplices als deren Alphabet reduciret, und aus solches alphabets combination wiederumb alle Dinge, samt ihren theorematibus, und was nur von ihnen zu inventiren möglich, ordinata methodo, mit der Zeit zu finden, ein weg gebahnet wird. Welche invention, dafern sie wils Gott zu werck gerichtet, als mater aller inventionen von mir vor das importanteste gehalten wird, ob sie gleich das ansehen noch zur zeit nicht haben mag [Vol. I, p. 57].

This gigantic plan involves several aspects on which Leibniz worked during his whole life. There was the analysis or reduction to primitives of the immense knowledge that had been accumulated, even then, by all sciences from mathematics to theology. There was the problem of choosing the right kind of symbols to represent the primitives and their interrelations. Finally, a method had to be developed that would “mechanically” solve the fundamental problem of the art of discovery as Le...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Approaches to Heuristics: A Historical Review

- 2 An Evolutionary Approach to Cognitive Processes and Creativity in Human Being

- 3 An Evolutionary Approach to Hypothesis and Concept Formation

- 4 Inspiration and Thinking in Mathematics

- 5 Heuristics and the Axiomatic Method

- 6 Heuristics and Cognition in Complex Systems

- 7 Heuristics, Mental Programs, and Intelligence1

- 8 On Generating Procedures and Structuring Knowledge

- 9 Guidance of Action by Knowledge

- 10 Informal Heuristic Principles of Motivation and Emotion in Human Problem Solving

- 11 Jokes and the Logic of the Cognitive Unconscious

- 12 The Heuristic of George Polya and Its Relation to Artificial Intelligence

- 13 Problems of Representation in Heuristic Problem Solving: Related Issues in the Development of Expert Systems

- 14 Toward a Theory of Heuristics

- Author Index

- Subject Index