- 308 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Effective Teaching of Physical Education

About this book

This text provides comprehensive and practical help and advice for new entrants to the profession, and concentrates on the teaching skills and professional competencies needed to become an effective teacher of physical education.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Effective Teaching of Physical Education by Mick Mawer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralCHAPTER 1

Introduction: Becoming a Physical Education teacher

Why teach PE?

I gained a lot from PE when I was at school and was very much influenced by the PE staff. I want children to at least have a chance of gaining what I have from PE. I wish to teach children the abilities I have. (BEd student teacher)I enjoyed sport a great deal. I felt that becoming a PE teacher would allow me to pursue my interest as well as being able to pass on my knowledge and skill to others. I personally get a great deal of satisfaction from watching children enjoy sport. (BEd student teacher)I wanted to work in an outdoor environment and was attracted to some kind of social service. (Male PE teacher – 41 years of age)Enjoyed sport and wanted to link a career to it. (Male PE teacher – 29 years of age)

Why do people want to teach PE? The above quotations from students in training and experienced teachers of PE taking part in the Teachers of Physical Education (TEPE) Project reflect an overiding interest and enjoyment of sport and a feeling that they wanted to pass on their knowledge, enthusiasm and love of sport to young people. When asked ‘Why did you want to become a PE teacher?’ the majority of students in teacher training mentioned some aspect of ‘working with children’ (65%) and ‘enjoyment of sport/physical activity’ (60%) as their main reasons for embarking on a career in teaching physical education. This is not new. In a study of 50 male and 50 female PE teachers in Hampshire secondary schools by Evans and Williams (1989) the most common reason for entering the PE profession was ‘love of sport’, and the positive influence that their PE teachers had had on them during their own school careers.

Hendry’s (1971) earlier study noted that career choice in physical education related to the possession of high skills ability and a liking of children.

Student teachers in the United States of America appear to have similar reasons for chosing a career in physical education as their UK cousins. In Belka, Lawson and Lipnickey’s (1991) study of 55 undergraduates at the beginning of their course of training the majority mentioned wanting to use their ‘athletic ability’, ‘to work with people’ and ‘to be helpful to others’, as the main reasons for embarking on a career in PE teaching.

Dodds and her colleagues (Dodds et al., 1991) also found that service (helping people), continuation (staying associated with sport) and doing work that’s fun, were the main occupational decision factors in their study of teacher/coach recruits.

Why students decide upon a career in teaching physical education is the first stage in what Lawson (1983) suggests are the three phases of teacher socialisation into the profession. The first phase occurs prior to initial training and is termed ‘anticipatory socialisation’ (Dewar, 1989). This phase involves such factors as exposure to PE teachers and participation in the PE curriculum during our own school years as pupils. As a consequence of these experiences we develop perceptions and ‘images’ of the profession of teaching physical education.

Images of teaching Physical Education

Lawson (1983) uses the term ‘subjective warrant’ to describe the perceptions and other information accumulated about a particular professional role: ‘The subjective warrant consists of each person’s perceptions of the requirements for teacher education and for actual teaching in school.’ (p. 6)

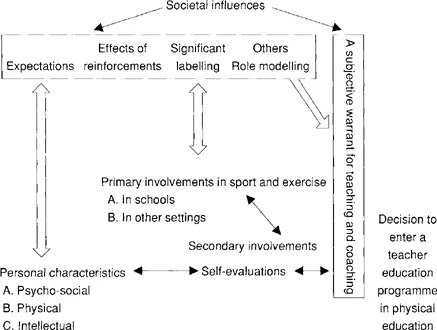

It appears that we learn a great deal from the many hours that we spent at school in the gym and on the playing field about what teaching is all about. We may then wish to emulate the attributes and characteristics of our favourite PE teachers and coaches. However, as Lawson (1983) points out, other factors do play a part in the formation of the subjective warrant, and these are shown in Figure 1.

Our teachers and coaches, family members and the opportunity to stay involved in sport and to help others through teaching and coaching, are all factors influencing the choice of a career in physical education. In fact, at least one study has shown that our own experience as pupils at school may well influence our professional practice when we become teachers more so than initial training courses (Atkinson and Delamont, 1985). Schempp (1989) developed this theme by examining the notion originally put forward by Lortie (1975) that an ‘apprenticeship by observation’ period may exist in which future physical education teachers are influenced by their days being taught PE at school. In his study of 49 student PE teachers, Schempp (1989) concluded that this apprenticeship period as a pupil: ‘…informs the prospective physical educator of the tasks of teaching, influences assessment strategies for determining the quality of teachers, and helps shape the analytic orientation towards each teacher’s professional work.’ (p. 36)

Figure 1 Factors influencing the Subjective Warrant for a career in teaching Physical Education Source: Lawson (1983) p. 6.

However, Schempp (1989) did not feel that: ‘…the past would determine the future for PE,’ – suggesting that student teachers of PE may not be tempted to emulate the style and approach of their own PE teachers and ignore what they had learned at college:

Those assuming teaching roles are not the same people as those who were students, nor are the schools they enter to teach the same as they left as students. Although tradition stands strong in the process of schooling, time washes anew the circumstances of the educational experience. Teachers will, most certainly, carry with them the lessons learned from their apprenticeship and these lessons will inform their practice as professionals. (Schempp, 1989, p. 36)

The important point to make here for the beginning physical education teacher is to be aware of the dangers of relying too much on one’s ‘apprenticeship by observation’ when preparing to teach. Past experience as a pupil may offer a wealth of knowledge of the personal qualities and ‘presence’ of teachers, but this would only be valuable if such reflection is critical and leads to the continued personal development of the student teacher in terms of improving professional practice.

Regardless of Schempp’s (1989) optimism, there is the danger that the results of such early observation of one’s own PE teachers may be so persistent that formal training is unable to alter images and beliefs about teaching already learned. As Graber (1989) and Lortie (1975) have pointed out, in attempting to emulate their favourite teachers, students teachers don’t appreciate that they are only imagining what teaching is like. Such a view of teaching is therefore based on intuition and imitation of personalities rather than pedagogical principles. However, whilst taking into account the dangers of an uncritical imitation of one’s own PE teachers, it is worth pointing out that student teachers in their early years of training are generally in agreement with other members of the PE profession when identifying the personal qualities of ‘good’ teachers. Student teachers returning from their first teaching practice are beginning to build up an image of the personal qualities of ‘good’ teachers based not only on their ‘apprenticeship by observation’ as pupils, but also their apprenticeship as fledgling teachers working alongside experienced teachers.

As part of the ‘Teachers of Physical Education’ (TEPE) Project, 87 student teachers were asked: ‘What attributes, personality characteristics, interpersonal and professional skills do you think a good PE teacher should have?’

The most frequently mentioned attributes and personality characteristics of a good PE teacher were considered to be: enthusiasm (35.6%), sense of humour (35.6%), approachability (29.9%), patience (21.8%) and the ability to be a good communicator (50.6%) and organiser (43.7%). Other characteristics of good PE teachers mentioned by some respondents included being outgoing, extrovert, fair, open-minded, easy going, the ability to get on well with or relate well to people and pupils, confident, showing consideration for others, a cheerful outlook, lighthearted, sociable, inventive, caring, articulate, assertive and has ‘leadership qualities’. The student teachers also felt that good PE teachers were knowledgeable (35.6%) and skilled at sport, were committed to their chosen career, had good discipline, showed consideration for others, had the ability to listen, were aware of pupil differences and understood children. These findings are very similar to the American study of 224 pre-service and experienced teachers of PE by Arrighi and Young (1987). When asked the question, ‘What is an effective physical education teacher?’, 25% of the total responses referred to such personal qualities as enthusiasm and patience, linked to other characteristics related to skill knowledge, personal skill and personal fitness.

At the SCOPE conference at Nottingham in 1985 (SCOPE 1985) leading physical educationists involved in the initial training of PE teachers in the United Kingdom addressed the concept of ‘Teaching Quality and Physical Education’. In the conference working groups delegates were asked to identify the characteristics of teaching quality in physical education. The groups listed the following personal qualities as being desirable in new recruits to the profession: enthusiasm (overt enthusiasm and the ability to convey it to others), a sense of humour, empathy and sensitivity to others, the ability to relate to others, adaptability/flexibility in thinking, communication skills, cooperative attitude, imagination and initiative, the ability to organise, confidence and an ability to engender confidence, self-motivation, personal ‘presence’, articulate and good use of voice, capable of self-analysis, commitment and leadership qualities.

Such personal qualities may be an important factor in becoming an effective teacher. For example, the qualities of ‘good teachers’ as identified by HMI in their paper ‘Education Observed’ (DES, 1985) included:

…such a personality and character that they are able to command the respect of the pupils, not only by the knowledge of what they teach and their ability to make it interesting but by the respect which they show for the pupils, their genuine interest and curiosity about what pupils say and think and the quality of the professional concern for individuals. It is only where this two-way passage of liking and respect between good teachers and pupils exists, that the educational development of pupils can genuinely flourish, (p. 3)

The Department of Education and Science (DES, 1984) have in fact made certain recommendations to teacher training institutions concerning the personal qualities that those interviewing prospective new recruits to teaching should look out for: ‘In assessing the personal qualities of candidates, institutions should look in particular for a sense of responsibility, a robust but balanced outlook, awareness, sensitivity, enthusiasm and facility in communication.’ (p. 10)

Therefore, there appears to be considerable agreement between the DES, lecturers in higher education and student teachers in their early years of training, concerning the personal qualities of ‘good’ teachers of physical education. These personal qualities and ‘images’ of good teachers are seen by the profession as important basic attributes for the development of an effective teacher of physical education. But it is only a starting point. There are a number of stages on the road to becoming an effective physical education teacher.

Stages in teacher development

When the question is asked, ‘How long does it take to become an effective physical education teacher?’, many feel that the process may well start earlier than was originally thought. It appears that our perceptions of the profession of teaching physical education may be formed by our earlier contacts with our family and teachers, as well as the coaches that we meet as pupils at school and as members of our local junior sports club.

According to a number of workers in the field of teacher development in physical education there may be a number of stages in the process of becoming an effective teacher of physical education.

We have already noted what Templin and Schempp (1989) refer to as a ‘pre-training period of socialisation’ into the profession which may occur prior to initial training, but the first formal stage in becoming a teacher will take place during teacher training. Feiman-Nemser (1983) has suggested three stages beyond the pre-training period in the development of a teacher:

An Induction stage – related to one’s experience in training as a student teacher, but also including experiences in the first year of teaching.A Consolidation stage – where concerns about control and being liked by children common in the induction phase give way to beginning to appreciate how to differentiate learning experiences for different ability levels and being able to identify why some lessons go well and others do not.‘Master teacher’ stage – at this stage Feiman-Nemser believes that after several years one begins to orchestrate a variety of teaching skills efficiently, have clearly planned schemes of work, clear lesson objectives, with the majority of lessons taught being effective and satisfying to both teacher and class.

Metzler (1990) has adapted Feiman-Nemser’s stages of teacher development to physical education, and includes pre-service, student teaching, induction and veteran stages in his model.

Metzler’s ‘pre-service’ stage includes not only the undergraduate course (if taking the PGCE route), but also what has been discussed earlier as ‘anticipatory socialisation’ while a pupil at school. However, Metzler does believe that initial formal training marks the onset of this stage as do courses in teaching methods and periods of school experience.

The ‘student teaching’ stage involves the transition from using the skills learned on the teacher training course and school experience to transferring these skills to the real world of full-time teaching on teaching practice. Metzler (1990) believes that students: ‘… should have acquired a wide repertoire of effective instructional skills through simulation and lead-up experiences within the pre-service stage. Finding strategies that help transfer those skills from limited contexts to intact classes within a full teaching day is the difficult task for supervisors and teachers in this stage.’ (p. 17)

The ‘induction’ stage is seen by many as being those crucial first few years following initial training when teachers hold a full-time teaching post in schools for the first time. Metzler (1990) believes that during this stage teache...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series List

- Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Acronyms

- 1 Introduction: Becoming a Physical Education teacher

- 2 The new teacher of Physical Education

- 3 Understanding teaching

- 4 Effective teaching skills and professional competencies

- 5 Planning and preparation

- 6 Creating an effective learning environment

- 7 Maintaining an effective learning environment

- 8 Teaching styles and teaching strategies

- 9 Direct teaching strategies and teaching skills

- 10 Teaching strategies for greater pupil involvement in the learning process and the development of cross-curricular skills

- 11 Assessment of pupil progress

- 12 Supporting the new Physical Education teacher in school

- References

- Index