- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Social Life of Children in a Changing Society

About this book

This book developed from a symposium in which participants examined childhood socialization from a number of perspectives and with several disciplinary lenses. The major purpose of the symposium and thus of this volume is to provide an integrative, multidisciplinary discussion of the social development of preschool and young elementary school-aged children. As a result, there are contributions to this volume from anthropologists (Leacock, Ogbu), psychologists (Lippincott, Mueller, Ramey and Snow), sociologists (Borman, Denzin) and scholars who have self-consciously adopted an interdisciplinary framework. First published in 1984. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Social Life of Children in a Changing Society by K. M. Borman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicología & Historia y teoría en psicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

7 The Abecedarian1 Approach to Social Competence: Cognitive and Linguistic Intervention for Disadvantaged Preschoolers

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

“….it is not easy for an education, with which love has mingled, to be entirely thrown away.”

—Rousseau

It is axiomatic in education that environments affect development. It is also generally accepted that children from poor and under-educated parents have more difficulty in school than children from affluent and well-educated parents (see, for a recent empirical example, Ramey, Stedman, Borders-Patterson, & Mengel, 1978). The causes of this school difficulty, and in the extreme, school failure, are undoubtedly multiple and interactive. Educators have been assigned the large task of carrying out social reform: of diminishing the likelihood of school difficulty or school failure for the disadvantaged, and thereby increasing their likelihood of socioeconomic success. That facilitating educational success can guarantee later socioeconomic success is an assumption society has rightly begun to question: education may be a necessary rather than sufficient condition for social or economic achievement. Given this large task, educators have been allotted relatively meager resources for accomplishing it. They are forced, then, to use the most powerful tools that limited knowledge and resources have to offer.

Education always occurs in particular cultural contexts with presumptions being made about the backgrounds of the learners. Therefore, to be maximally effective in exerting educational leverage to the benefit of disadvantaged children, it is important that we know the disadvantaged child’s typical ecologies. Knowledge of the typical ecological forces will allow more precise and carefully targeted use of the limited resources available to the educator. As a beginning step in the generation of that knowledge, this chapter will summarize the information which has been obtained from a longitudinal early intervention program that has collected extensive preschool ecological and child development data for the past 10 years. The chapter begins with a description of the child’s physical, social, and attitudinal ecologies and proceeds to an extensive description of the educational settings and practices that were designed as part of the Carolina Abecedarian Project to assist young disadvantaged children attain educational competence. We present a sampling of results from this work on experimentally altering the educational ecology of children of poverty and conclude with the implications that we draw from these results concerning social policy for preschool programs.

ECOLOGY OF THE DISADVANTAGED PRESCHOOLER

The disadvantaged child lives in a very different world from his upper middle- class peer. His world looks different, smells different, tastes different, feels different and sounds different. To be sure, there are similarities. Both can know joy, love, fear, and want; but, at almost every turn the paths for the advantaged and the disadvantaged diverge. The more desirable of these two paths is almost always trod by the advantaged—and, both the advantaged and disadvantaged know this truth. It is these differences in ecologies that we assume to be of paramount importance for determining life satisfaction and contribution to society. We begin this chapter by describing some of the things that we have learned in the past 10 years of the Abecedarian Project about the physical, social, and attitudinal ecologies of advantaged and disadvantaged children. It is these predisposing ecologies that are the context for our educational efforts.

Physical Environment

Information about the physical setting of the home for advantaged and disadvantaged infants has been presented by Ramey, Mills, Campbell, and O’Brien (1975). Using Caldwell, Heider, and Kaplan’s (1966) The Inventory of Home Stimulation we found that lower socioeconomic status homes were characterized by relatively disorganized environments and lacked age-appropriate toys and opportunity for variety in daily stimulation when infants were 6 months of age. The homes also tended to be poorly lighted, to have a high density of people, and to vary considerably from one another on many physical and other dimensions.

Table 7.1 is an attempt to provide a quick synopsis of some salient characteristics of these homes.

Several points are to be noted from Table 7.1. First, 45% of the families live in households containing five or more members. Thus, the households tend to be somewhat larger than is typical for today’s nuclear family. Further, about 15–18% of the houses are rated as dilapidated and unfit for occupancy. The children tend to sleep in rooms containing not only other children but also one or more adults which in all probability indicates a serious crowding situation. Finally, these somewhat crowded households typically contain one or more members who smoke. The extent to which these conditions contribute to the child’s development is at present unknown; however, it is abundantly clear that these physical arrangements are vastly different from those enjoyed by socioeconomically more advantaged children. Further, as the second column of figures in Table 7.1 indicate, there is remarkable stability in these characteristics over a 3-year period.

Attitudinal Environment

Attitudes represent a set of assumptions which bear some as yet only partially understood relationship to specific parenting practices. Nevertheless, the attitudes of advantaged and disadvantaged parents differ in ways that are parallel to the differences in their children’s development. Whether these attitudinal differences are causes or correlates of child change is at present unknown. However, they are part of the psychological environment of the child and probably are not trivial. We know that by the time their infants are 6 months of age lower socioeconomic status (SES) mothers score as more authoritarian and less democratic in their child-rearing attitudes but also as less hostile toward and rejecting of the homemaking role than their more advantaged peers. They also perceive themselves, probably realistically, as more controlled by external forces than as internally controlled (Ramey & Campbell, 1976). Such attitudes lead us to presume that there is less creative flexibility in child rearing and more pessimistic fatalism in the environment of the disadvantaged child compared to the advantaged one. Further, this somewhat glum maternal perception of life exists essentially from the child’s birth and is relatively unchanged during, at least, the first 2 years of its life (Ramey, Farran, & Campbell, 1979).

Table 7.1

Information on the Physical Ecology of High- Risk Children in the First and Third Years of Life

Information on the Physical Ecology of High- Risk Children in the First and Third Years of Life

Characteristic | 1st Year N = 56 | 3rd Year N = 40 |

Number in Household | ||

≤5 | 55% | 48% |

5–7 | 45% | 37% |

≥8 | 13% | 5% |

% houses with 1 or more other preschool children | 98% | 100% |

% houses with 1 or more elementary school children | 52% | 47% |

% houses with 1 or more junior or senior high school students | 44% | 27% |

Type of Housing | ||

Single Family | 53% | 35% |

Multiple Family | 47% | 65% |

Dilapidated | 18% | 15% |

Sleeping in Room with Child | ||

1 or more preschool children | 7% | 26% |

1 or more older children | 41% | 33% |

1 or more adults | 73% | 77% |

Families with 1 or more members who smoke | 80% | 82% |

Social Interactional Environment

Beginning as early as 6 months and continuing throughout the preschool years, the disadvantaged child is interacted with by adults somewhat differently than is the advantaged child. The differences appear to be smaller in early infancy and to become larger as the child grows older. For example, Ramey, Mills, Campbell, and O’Brien (1975) have reported that the mothers of disadvantaged infants tend to be less responsive verbally and emotionally, more punitive and less involved with their infants when observed within their own homes. These results have been replicated and extended in a recent report by Ramey, Farran, and Campbell (1979) who used both naturalistic mother-child observations in the child’s home and constrained observations in a laboratory setting. We found that disadvantaged mothers talked less to their 6-month-old infants than advantaged mothers even though those two groups of infants did not differ in their rates of nonfussy vocalizations. At 20 months, advantaged mothers continue to talk more to their children and to interact with them more frequently in a laboratory setting. Farran and Ramey (1979) have recently reported a factor analysis from these interactional observations in which a first factor labeled as “Dyadic Involvement” was isolated at both 6 and 20 months. Disadvantaged and advantaged dyads did not differ significantly on this dimension at 6 months but were different at 20 months with the advantaged dyads scoring as more involved. Further, the factor scores on this dimension significantly predicted the child’s IQ at 48 months.

Thus, some of the evidence available from the Abecedarian Project seems to suggest that infants and their mothers share different social, attitudinal, and physical ecologies from the child’s early infancy depending on what social niche they occupy. The at-home and laboratory observations suggest that the early language environments of advantaged and disadvantaged children may be a major difference between the two groups. Further, these language environments are linked to the child’s subsequent general intelligence and, presumably, to his subsequent school achievement. Therefore, to the extent that this relationship is causal and not just correlative, it becomes a particularly salient target for educational intervention.

After a brief description of the overall organization of the educational intervention component of the Abecedarian Project we present a conceptual framework and plan for daily action that guides our language-oriented intervention program during the latter part of the preschool years.

DESCRIPTION OF THE ABECEDARIAN INTERVENTION PROGRAM

Admission of Families

The Carolina Abecedarian Project began in 1972 to intervene with infants and children believed to be at high risk for school failure. Families were referred to the project through local hospitals, clinics, the Orange County Department of Social Services, and other referral sources. Once families had been identified as potentially eligible, a staff member visited them at home to explain the program and to determine whether they appeared to meet selection criteria. If so, mothers were invited to the Frank Porter Graham Center for an interview and psychological assessment.

During their visit to the Center, which typically occurred in the last trimester of pregnancy, demographic information about the family was obtained and mothers were assessed with the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS; Wechsler, 1955). Final determination of eligibility was made following this visit. Criteria for selection included maternal IQ, family income, parent education, intactness of family, and seven other factors that were weighted and combined to yield a single score called the High Risk Index (see Ramey & Smith, 1977, for details). Only families at or above a predetermined cutoff score were considered eligible.

We admitted four cohorts or groups of families between 1972 and 1977. The oldest children are now over 10 years of age and are attending the local public schools; the youngest children are now approximately 5 years of age. Of 122 families judged to be eligible for participation, 121 families initially agreed to participate knowing that they would be assigned randomly to an educationally treated group or to a control group. When these 121 families were randomly assigned to the Day Care group or to the Control group, 116 or 95.9% accepted their group assignment. Of these 116, three children have died and 1 child has been diagnosed as retarded due to organic etiology. Not counting these four children we have, then, a base sample of 112 children. Of these 112 initially normal children, 8 have dropped from our sample as of September 1, 1978.

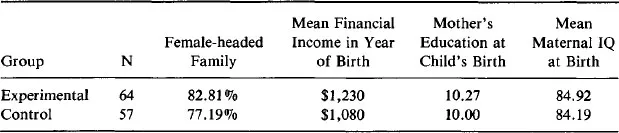

Table 7.2

Demographic Data by Experimental and Control Groups Cohorts I-IV

Demographic Data by Experimental and Control Groups Cohorts I-IV

Thus, not counting attrition by death or severe biological abnormality, 92.9% of our sample is intact. Some characteristics of families admitted to the Abecedarian Day Care and Control groups are summarized in Table 7.2.

General Characteristics of The Early Childhood Education Program

The early childhood program serves up to 50 children who participate in the Abecedarian project. Most of the children enter the program at 6 weeks and stay in the program until they enter public school kindergarten. When there are openings for additional children, they are recruited from the community to pr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Preface

- I: INTRODUCTION

- II: PARENTS AND OTHERS: THOSE WHO INFLUENCE CHILDREN’S LIVES

- III: LANGUAGE AS A PRIMARY SOCIALIZER: NORMALLY DEVELOPING CHILDREN

- IV: LANGUAGE AS A PRIMARY SOCIALIZER: DEVELOPMENTALLY DELAYED CHILDREN

- V: THE CROSS CULTURAL PERSPECTIVE

- VI: ENDNOTE: THE POLITICAL USES OF CHILDHOOD

- Author Index

- Subject Index