![]()

THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL PERSPECTIVES

![]()

A Strategic Framework for Developing and Assessing Political, Social Issue, and Corporate Image Advertising

Thomas J. Reynolds

Richmont Partners

Steven J. Westberg

Wirthlin Worldwide

Jerry C. Olson

Penn State University

Means-end theory provides an understanding of the basis of consumers’ purchase and consumption decisions (Gutman & Reynolds, 1979). Means-end research has focused on measuring the personal or subjective relationships between products (defined by attributes) and consumers (defined by values). This product/consumer relationship is the key for understanding how products derive personal relevance and is useful in developing effective positioning and advertising strategies. Means-end theory includes laddering (Olson & Reynolds, 1983) and MECCAS (Reynolds & Gutman, 1984). Laddering is an interview methodology used to uncover consumers’ means-end chains, and MECCAS is a model for translating means-end data into the components of advertising strategy. Most means-end research has focused on the strategic assessment of consumer goods advertising (Gutman & Reynolds, 1987). Still unexamined, however, is how nonproduct advertising, including ads used for political campaigns, social issues, and corporate image, taps into the decision making process. We provide a conceptual framework, extended from MECCAS, for understanding these diverse types of advertising communications as well as specify how to measure their strategic delivery or effectiveness.

OVERVIEW OF MEANS-END THEORY AND LADDERING

To develop effective positioning strategies, marketers need to understand what consumers think about when they make product choice decisions. Several academic studies have addressed this research issue. Fishbein (1967) proposed a model in which a person’s attitude toward an object depends on the individual’s beliefs about the different attributes of the object, weighted by their importance. Lehmann (1971); Bass, Pessemier, and Lehmann (1972); and Bass and Talarzyk (1972) found support for this attribute-based model in different applications. Holbrook (1978) elaborated the concept of attributes by distinguishing between “logical, objectively verifiable descriptions of tangible product features” and the “emotional, subjective impressions of intangible aspects of the product.” Myers and Shocker (1981) differentiated between product attributes and product benefits. Still another perspective focused on the role of personal values as a determinant of attitude and ultimately product choice (Homer & Kahle, 1988; Rokeach, 1973; Vinson, Scott, & Lamont, 1977). However, all these approaches lack the critical understanding of why product attributes are important to people.

Means-end theory (Gutman, 1982; Gutman & Reynolds, 1979), based on personal values, explains the relationships between attributes, benefits (positive consequences of the attributes), and personal values (desired personal states of the person who buys and uses the product). These three levels of a means-end chain provide a complete perceptual connection between a product and a consumer. In the means-end perspective, the product is defined by a collection of attributes, both concrete and abstract. These product-specific attributes yield consequences when consumers use the product. Consequences are important based on their ability to satisfy the personally motivating values and goals of the consumer. How strongly a specific consequence leads to the satisfaction of these values directly determines the relative importance or salience of the associated attribute. A means-end chain, then, is a sequence of attributes, consequences, and values that provides a perceptual link between a product and a consumer. Because values determine the relative importance of the consequences and therefore the importance of the attributes, means-end chains help us understand the consumer’s decision making process.

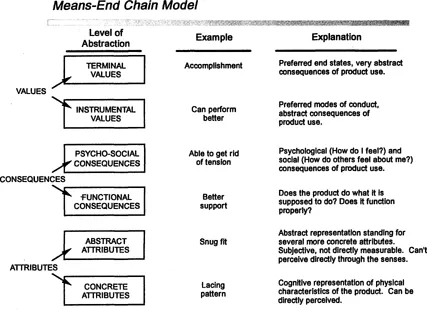

Means-end theory recognizes that product-related meanings exist at different levels of abstraction. The product is defined by attributes, which are the most concrete, tangible meanings while the person is defined by personal values, which are the most abstract, least tangible meanings. The elements at each level can be further subdivided based on degree of abstraction (see Fig. 1.1). Concrete attributes can be objectively measured or evaluated such as size, weight, color, and ingredients. Abstract attributes are more subjective or personal descriptors such as taste, smell, and appearance.

Likewise, consequences are categorized as functional and psychosocial. Functional consequences are physical such as Gives Me Energy and More Leg Room, while the psycho-social consequences involve psychological or sociological benefits such as mood affects, feelings, social interactions, and ego builders. Values can be classified as instrumental (a mode of behavior that can lead to higher level values, e.g., Accomplishment) or terminal (an end state of existence such as Self-Esteem). Product attributes, functional and psychosocial consequences, and personal values also represent the strategic elements of positioning and communication strategy.

FIG. 1.1. Means-end chain model. Adapted from Peter and Olson (1987), Consumer Behavior. New York: Irwin, p. 120.

Laddering (Olson & Reynolds, 1983; Reynolds & Gutman, 1988) is the interviewing and analysis methodology that uncovers and summarizes individuals’ means-end chains that are associated with the reasons for choice between products. Laddering involves asking a series questions with the form: “Why is that important to you?” For example, for light beer, an individual might choose Miller Lite over Bud Light because “it has fewer calories.” Fewer calories are important to the person because it means the beer “doesn’t fill me up so much,” a functional consequence of fewer calories. This outcome leads to the psychosocial consequence of “I can drink more with my friends.” In turn, drinking more with friends is important because it helps the person feel “more a part of the group,” which is the motivating personal value or goal that drives the decision. This means-end chain, which links “fewer calories” to “part of the group,” represents the consumer’s reason for product differentiation and choice.

An initial product distinction (e.g., fewer calories) can be elicited using one of several techniques (Reynolds & Gutman, 1988), including triadic sorting, preference-consumption differences, or differences by occasion. Each of these techniques requires the respondent to choose a brand from a competitive set and the primary reasons for that choice. Inasmuch as people may have multiple reasons for choice in different consumption occasions, each respondent typically can provide between 4 and 8 unique means-end chains (or ladders) for a given brand.

Means-end chains for a market segment can be summarized in a Consumer Decision Map (CDM), which is a graphical representation of the most frequent elements at each level of abstraction and the major pathways of connection between the elements (Olson & Reynolds, 1983; Reynolds & Gutman, 1988). As such, the CDM is a managerial tool to help translate the consumer’s decision-making criteria into marketing strategy. CDM construction requires a series of steps: (a) means-end chains elicited from laddering are analyzed for content, (b) all mentioned ideas are collapsed into an inclusive set of meaning codes, (c) an implication matrix is constructed that contains the frequencies of all direct and indirect associations between the coded elements, and (d) the most frequently mentioned connections between codes are selected to build the map.

In general, 80% to 90% of all consumers’ ladders for a category can be represented by the elements and connections on the map. Therefore, the CDM can be thought of as a perceptual playing field of the category for determining and evaluating positioning strategy because it reveals the meanings of the reasons for product choice. Of course, the goal of the positioning strategy will determine the competitive sets or the occasions from which the choice distinctions are elicited. For example, if the primary strategic issue is brand versus brand competition within a category, the competitive set might be limited to in-kind category competitors and the occasions might include only the most frequent prototypical occasions of consumption. If the strategic issue is one of category growth, the competitive set might include functional competitors and the occasions might be nontypical.

Once the CDM has been developed, strategic positioning options can be discussed. A positioning strategy is defined as the specification of strategic elements (product attributes, functional consequences, psychosocial consequences, and personal values) that will be the perceptual connection between the product and the consumer. Ideally, a positioning strategy will include elements that give consumers motivating reasons to choose the brand. As such, strategy development based on a Consumer Decision Map can follow one of four routes (Gengler & Reynolds, 1995):

1. The first is discovering a significant, yet untapped consumer perceptual orientation that is not currently associated with any products or brands in the map. This requires looking where the elements and the connections do not yet exist.

2. The second option involves establishing perceptual “ownership” of a pathway by creating a stronger link between elements that currently are only weakly associated.

3. The third option involves developing new meanings by connecting two unrelated ideas.

4. The fourth option involves creating new meaning by adding a new element to the CDM and associating...