![]()

Introduction to Working Memory

Most adults produce and comprehend their native language rapidly, accurately and effortlessly. Speaking and listening can be combined with many of other everyday activities with little detectable cost to the language user. It is only when more objective indices of linguistic behaviour are considered that the huge reserve of expert knowledge that is necessary to support this “language skill” becomes apparent. The typical adult knows the sound structure, meaning and spelling of many tens of thousands of words, constituting a kind of mental dictionary acquired through personal experience. Knowledge about language is not, however, restricted to lexicon-like entries about individual words. The skilled language user has also mastered the grammar of the native language. The grammar is a complex system of abstract syntactic rules that allows the speaker to combine words in an infinite number of phrases and sentences. It also enables the listener to understand the messages produced by others. In addition, the production and comprehension of language is guided by knowledge about both the pragmatics of language use and the conventions governing discourse between individuals.

The unique ability of humans to develop this extensive knowledge base for their native language has been attributed to innate capacities specialised for the acquisition and processing of language (e.g. Chomsky, 1957). However, this position does not explain the psychological mechanisms by which linguistic knowledge is either acquired during childhood or used in the course of language activity. In this book, we focus on the contribution to acquisition and processing of language of one particular mechanism, working memory. Baddeley and Hitch (1974) used this term to describe the short-term memory system, which is involved in the temporary processing and storage of information. They suggested that working memory plays an important role in supporting a whole range of complex everyday cognitive activities including reasoning, language comprehension, long-term learning, and mental arithmetic.

Intensive research activity has been stimulated by the working memory approach. The adequacy of the working memory model as a theoretical account of short-term memory in both adults and children has been investigated and the model itself has been refined (Baddeley, 1986). In addition, researchers have been concerned with identifying those everyday cognitive activities which involve working memory. In recent years, there has been considerable interest in the contribution of working memory to language, resulting in a broad and diverse range of evidence. Some of this evidence points to a clear involvement of working memory in language, whereas other studies identify aspects of language processing in which working memory appears to play little part. It is, however, clear that working memory is important in language processing, and that the richness and complexity of its role is such that it is likely to be a fruitful research area for many years to come. The research literature on this topic is already extensive and distributed across a wide range of both general and specialised journals. We believe that a review of the area is timely and that it may help the area to advance. The aim of this book is to provide such a review. Inevitably, some aspects of language processing have been more fully investigated than others. For this reason, interpretation in some parts of the book is by necessity speculative, representing “first passes” at theory rather than polished theoretical conclusions. We hope that these speculations are useful in stimulating further research and counter-theorising.

The task of evaluating working memory involvement in language is not a straightforward one, partly because of the inconsistent usage by psychologists of the term “working memory”. It is often not clear whether different researchers are talking about the same psychological mechanisms when they discuss working memory involvement in various aspects of language processing. Some researchers use the term to denote a general processing system that has a limited capacity (Daneman & Carpenter, 1980; Kintsch & van Dijk, 1978; Pascual-Leone, 1970). Others use the term to refer to an essential component of production system models of cognition, a component that is not necessarily limited in capacity (Anderson, 1983). The term “working memory” is used more specifically in this book to refer to the current version of the working memory model developed by Baddeley and Hitch (1974). This well-specified theoretical model of short-term memory is used as a framework for the analysis of the contribution of working memory to language. Although we personally have found this framework to be productive, the principal aim of the present review is not to argue for such a model, but to use it to structure an overview of the available evidence concerning this crucial interface between memory and language, an overview that we hope will be useful to readers of a wide range of theoretical persuasions.

The aspects of language processing considered in the following chapters are vocabulary acquisition, speech production, reading development, skilled reading, and language comprehension. For convenience, each of these language processes is considered in separate chapters although, of course, in practice these distinctions are far from clear cut. Where available, evidence concerning the nature and extent of working memory involvement in each aspect of language processing is drawn from three traditionally distinct but increasingly interrelated types of study that differ principally in their subject population. The studies we term experimental employ normal adult subjects, the developmental studies use children, and the cognitive neuropsychological studies involve the testing of patients with acquired brain damage.

Data from children and adults has obvious value in elucidating the nature of working memory involvement in the acquisition of language skills and in skilled language behaviour. The relevance of neuropsychological data may, however, require more explanation. The cognitive neuropsychological approach has had increasing impact on theorising in mainstream cognitive psychology over the past decade (see Ellis & Young, 1988, for an evaluation of its contributions), and has been particularly influential in the evolution of the working memory model discussed later in this chapter. The unique value of neuro-psychological studies for theories of normal cognitive function arises from the opportunities provided by “natural experiments” in which brain damage selectively impairs a particular psychological mechanism. Studies of patients with highly specific deficits of working memory have been of exceptional value in identifying the contribution of working memory to language. It has become increasingly apparent that investigations of such patients can provide a rich source of information about the structure and functioning of short-term memory which both supplements and enhances the findings obtained from studies of normal skilled language users.

THE WORKING MEMORY MODEL

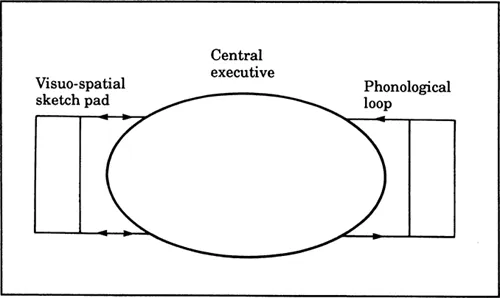

Baddeley and Hitch (1974) identified three components of working memory. The central executive component is the most important. Its functions include the regulation of information flow within working memory, the retrieval of information from other memory systems such as long-term memory, and the processing and storage of information. The processing resources used by the central executive to perform these various functions are, however, limited in capacity. The efficiency with which the central executive fulfils a particular function therefore depends on whether other demands are simultaneously placed on it. The greater the competition for the limited resources of the executive, the more its efficiency at fulfilling particular functions will be reduced.

The central executive is supplemented by two components which are termed “slave systems”. Each slave system is specialised for the processing and temporary maintenance of material within a particular domain. The phonological loop maintains verbally coded information, whereas the visuo-spatial sketchpad is involved in the short-term processing and maintenance of material which has a strong visual or spatial component. Figure 1.1 provides a simple schematic representation of the working memory model.

FIG. 1.1. A simplified representation of the Baddeley and Hitch (1974) working memory model.

The Central Executive

The central executive fulfils many different functions. Some of its primary functions are regulatory in nature: It coordinates activity within working memory and controls the transmission of information between other parts of the cognitive system. In addition, the executive allocates inputs to the phonological loop and sketchpad slave systems, and also retrieves information from long-term memory. These activities are fuelled by processing resources within the central executive, but which have a finite capacity. Cognitive tasks that have been suggested to involve the central executive include mental arithmetic (Hitch, 1980), recall of lengthy lists of digits (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974), logical reasoning (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974), random letter generation (Baddeley, 1966a), semantic verification (Baddeley, Lewis, Eldridge, & Thomson, 1984a) and the recollection of events from long-term memory (Hitch, 1980).

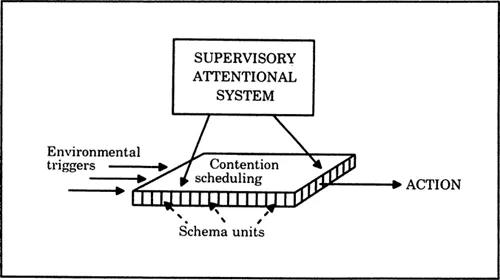

Theoretical progress on the central executive has been relatively slow, and experimental methodologies for studying the nature and extent of executive involvement in particular tasks are still under development. There have been, however, a number of important advances in understanding this component of working memory in recent years. Much of the current work on the regulatory functions of the central executive is guided by a model of the attentional control of action developed by Shallice (1982, 1988; Norman & Shallice, 1980). This model is shown in schematic form in Fig. 1.2. Action is controlled in two ways. Well-learned or “automatic” activities are guided by schemas that are triggered by environmental cues. Schemas can be hierarchically organised. Skilled drivers, for example, will have a driving schema that activates subroutines such as steering, gear-changing and braking schemas. When driving, the driving schema will be activated and all its subroutines primed, so that the sight of red lights at the rear of the car ahead should be sufficient to provide the environmental cue to trigger the braking schema.

FIG. 1.2. A model of the control of action. Adapted from Shallice (1988).

Potential conflicts between ongoing schema-controlled activities can be resolved routinely by the contention scheduling system. However, when novel activities are involved, or when the environment presents an urgent or threatening alternative stimulus, the higher-level Supervisory Attentional System (SAS) intervenes to control action. The SAS inhibits and activates schemas directly, and so can override the routine process of contention scheduling. By combining the powerful but resource-demanding SAS and the autonomous process of contention scheduling, human action is controlled by an efficient and responsive system.

Baddeley (1986) suggested that the SAS may correspond to the central executive. Useful insight into the nature of the SAS (and thus, the central executive) is provided by neuropsychological patients who, through either accident or disease, have experienced damage to the frontal lobes. It has long been known that damage to these cortical areas leads to disturbances in the conscious control of action which Baddeley (1986) has termed the “dysexecutive syndrome”. Frontal lobe patients typically show a paradoxical combination of behavioural perseveration, when they repeatedly perform the same action or say the same word or phrase, and distractibility, when they repeatedly pick up and use objects within reach, regardless of the social appropriateness of such actions. Shallice (1988) explains both types of behavioural disturbance as manifestations of an impairment to the SAS resulting from the frontal lobe damage. Perseveration results when the control of action is captured at a low level by a single powerful schema that continues to inhibit all other schemas. Because the SAS is impaired, it cannot intervene in order to damp down the activation of the schema. In contrast, distractibility arises in the absence of a highly activated schema. The patient is bombarded by a range of environmental triggers for different schemas, and the attentional system becomes dominated by environmental stimuli. The SAS system is impaired and so cannot intervene to boost selectively the activation of an appropriate schema and inhibit the activity of others.

There have been some important recent empirical and methodological developments concerning the central executive. Firstly, work with frontal lobe patients indicates that the executive may play a crucial role in the planning of future actions (Shallice & Burgess, 1991). A second advance was the development of an experimental task which appears to occupy the central executive. As tasks become more routine and automated, their demands on the central executive are assumed to decrease. A task that denies the possibility of automatisation should therefore put great demands on the central executive. One such task is that of random generation where, for example, the subject is required to produce a stream of letters in as random a sequence as possible. The existing alphabetic schema will tend to produce such stereotypes as ABC and WXY, and any simple alternative strategy is unlikely to be able to simulate randomness under rapid paced conditions, as indeed proves to be the case (Baddeley, 1966a). It is assumed that in order to generate successfully an unsystematic sequence of letters, the SAS is needed to overrule the routine processes which produced stereotyped and non-random letter sequences (Baddeley, 1986). Consistent with this view, the sequences become significantly less random (and more stereotyped) when the pace of the task is increased, and when the subject is involved in other concurrent activities. In other words, when the task either becomes highly demanding of the limited SAS resources or has to share them with other activities, its efficiency in controlling the production of unsystematic letter sequences is diminished.

One of the strengths of the random letter generation task is that it can potentially provide a tool for identifying central executive involvement in other activities. The way in which this can be done is by combining random letter generation with other tasks and measuring the cost for subjects of performing both activities concurrently rather than alone. If the central executive does have limited resources, tasks which also tax the executive should either show sizeable decrements when performed concurrently with random letter generation, or should lead to the generation of less random letter sequences. Recent work by Teasdale, Proctor, and Baddeley (in prep.; see Baddeley, in press) using this methodology has yielded intriguing results which directly link the central executive with conscious awareness.

It would, however, be misleading to suggest that the central executive is as yet uniquely identified with a single mechanism or model such as the Supervisory Attentional System. Some researchers do view the executive as a unitary system that may form the basis of the general factor of intelligence (Duncan, Williams, Nimmo-Smith, & Brown, 1991; Kyllonen & Chrystal, 1990). Other work, though, suggests that it comprises a range of relat...