![]()

1

The Fire of Liberty: Anarchism and Geography

Anarchism

The Greek word anarchos simply means ‘without a ruler’, and the word anarchy is often used to describe the social disorder, violence and chaos associated with the breakdown of authority and the widespread violation of law. Yet anarchists aspire to the absence of authority as a positive step on the road to building a new society in harmony with itself and with nature. Rather than being a negative term, anarchy is argued to be a positive social development, allowing each individual to blossom without the restrictions and confinements of authoritative power, law and control. By its nature, however, this tradition of dissent is eclectic and rather hard to pin down. Anarchist writers have tended to eschew definitive political programmes or organisational practices, and there has been little co-ordination between anarchist groups. Indeed, as Fauré suggests, anarchists are only really united in their opposition to authority in all its forms, and beyond that, there is enormous diversity within the tradition:

There may be – and indeed there are – many varieties of anarchist, yet all have a common characteristic that separates them from the rest of humankind. This uniting point is the negation of the principle of Authority in social organisations and the hatred of all constraints that originate in institutions fuelled on this principle. Thus, whoever denies Authority and fights against it is an Anarchist. (Fauré, quoted in Woodcock, 1977: 62; emphasis in the original)

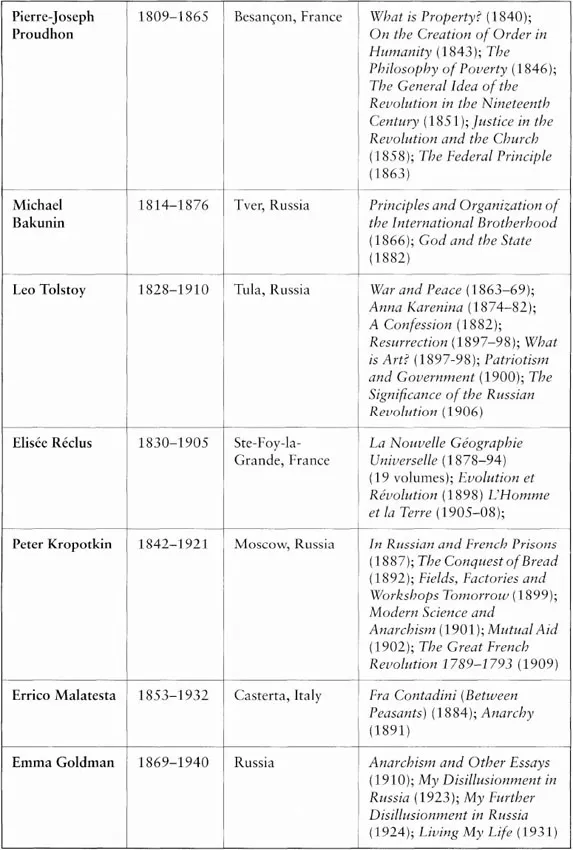

Despite its antecedents in all human rebellion, and particularly in the political battles of the English Civil War and the French Revolution, the anarchist tradition only came to self-consciousness in the mid-nineteenth century. Anarchist thinkers such as Pierre Joseph Proudhon, Michael Bakunin, Peter Kropotkin and Elisée Réclus were part of the wider socialist movement, and it was not until the 1870s that anarchists began to clearly distinguish themselves from marxists in arguments over the state, leadership and the mechanisms necessary to achieve social change. In this chapter we focus on the key ideas of these nineteenth-century anarchists (see Box 1.1), we explore the geography of anarchist organisation and experiment, and we consider the disciplinary implications of anarchist thought as far as geography is concerned. In this regard, it is significant that two of the key protagonists in the history of anarchism were practising geographers. A profound interest in the environment and in the diversity of social formations inspired both the geography and the anarchism of Peter Kropotkin and Elisée Réclus, and in their day, both men were celebrated as scholars of physical and regional geography (see Box 1.2 for details of the life of Kropotkin and Box 1.3 for a summary of Réclus’s life and work and his involvement in the Paris Commune of 1871). For our purposes, however, it is frustrating that Kropotkin and Réclus were not able to combine their anarchist ideas with their geographical scholarship as they might do today. Moreover, although a number of authors have sought to spell out the geographical implications of the anarchist writings of Kropotkin and Réclus (see Stoddart, 1975; Galois, 1976; Breitbart, 1975, 1981; Dunbar, 1978, 1981; Fleming, 1988; Cook and Pepper, 1990), there has been little development of anarchism in geographical theory and/or research, leaving us to speculate about what an anarchist geography might be like. To date, anarchism has made its clearest mark on geography by influencing a new generation of academics in the late 1960s and 1970s, inspiring them to question the authority, hierarchies and received wisdoms of the discipline. Such anarchist-inspired rebellion brought forth the new shoots of a radical geography associated with the journal Antipode, the development of new research themes, new disciplinary practices and the breakthrough to marxism discussed in Chapter 2. Anarchist ideas have inspired enormous change within the discipline, but as yet, they have spawned only the outlines of a tradition of geographical scholarship and there is plenty of scope for further elaboration.

Box 1.1 Key anarchist thinkers

Sources: Marshall, 1993; Miller, 1984

Box 1.2 The life of Peter Kropotkin

Prince Peter Alexeivich Kropotkin was born into the Russian aristocracy in 1842. His father was a high-ranking officer in the army, owning property in Moscow and an estate with 12,000 serfs in Kaluga. As was typical of his class, the young Kropotkin attended the military academy called the Corps of Pages from his early teens and he actually served as a Page de Chambre to the new Tsar, Alexander II. It was clear, however, that Peter was growing tired of this environment, and was developing more radical ideas, for in his early twenties he chose a posting with the Cossacks of the Amur in Siberia rather than opting for a safer career. The five years spent in Siberia proved to be a turning point for the developing revolutionary as he encountered a wild and uncharted landscape alongside anarchist ideas amongst the exiles confined to the region. His expeditions in the area proved to be the foundation of his later reputation as a physical geographer, and in particular, Kropotkin developed a new theory about the glaciology and the orography (the layout and alignment of the mountain ranges) of Asia. Moreover, his contact with people who lived without state control and regulation, building their own communities in such harsh conditions, helped to cement his anarchism. As he wrote in his Memoirs: ‘I lost in Siberia whatever faith in state discipline I had cherished before. I was prepared to become an anarchist’ (1962: 148).

Such interests were further stimulated when Kropotkin visited the Swiss Jura in 1872. The watchmakers of the region were famous for their political ideas and their communitarian lifestyles, and they had an enormous influence on Kropotkin’s developing anarchism. In addition, this visit to Western Europe brought Kropotkin into contact with the First International and the libertarianism of Michael Bakunin. On his return to Russia, Kropotkin sought out like-minded souls in his homeland, joining the Chaikovsky Circle for two years and sympathising with the peasant-based movement of the Narodniks. As a result of such activity Kropotkin was arrested and imprisoned for the first time in March 1874. Imprisoned in the notorious Peter and Paul Fortress in St Petersburg, he was only able to escape after three years. Exiled, he then moved back to Western Europe where he made new contacts in the UK, Spain, Italy and Switzerland, helping to set up a new anarchist journal called Le Révolte. Following his expulsion from Switzerland, Kropotkin was arrested in Lyon in 1882 where he was confined in prison until 1886. The French authorities were petitioned for his release by 15 British professors, the Royal Geographical Society, William Morris and Patrick Geddes, reflecting his international reputation as a scholar and political thinker.

When he was 44, Kropotkin moved to London, where he was to live for another 41 years. Here he was involved in the journal Freedom, gave regular lectures across the country and continued to travel abroad. Kropotkin kept up with his writing, although he led an increasingly quiet life – particularly when his support for the First World War alienated him from others in the anarchist movement. For the last three years of his life Kropotkin returned to Russia. The excitement of revolution was soured by his fears over Bolshevik tactics, however, and he died in February 1921 in a village outside Moscow. Over 100,000 attended the funeral of this anarchist thinker and geographer.

Sources: Kropotkin, [1899] 1962; Miller, 1976; Brietbart, 1981; Cook, 1990; Marshall, 1993

Box 1.3 Elisée Réclus and the Paris Commune

Elisée Réclus was born to a religious family (his father was a Protestant Pastor), in a small village in the Dordogne, France, in 1830. Reflecting the profession and interests of his father, he attended Berlin University to study Theology in 1851, although while he was there he attended some of the popular geography lectures delivered by Carl Ritter. This geographical interest was then further fuelled by travels to America and Ireland – where he witnessed the terrible devastation of famine – an experience that fed his growing interest in the socialist movement (see Chapter 5 for more on the Irish Famine). Thus it was that when Réclus returned to Paris in 1857 he had become a geographer and a radical, playing a key role in the Paris Geographical Society, in Bakunin’s secret Brotherhood and in the First International.

It was not, however, until the dramatic events of the Paris Commune that Elisée and his brother Elie became more clearly identified with the libertarian, or anarchist, wing of the socialist movement. The Commune began on 18 March 1871, when the workers of Paris took over the government of the city, in revolt against the authoritarianism and hardships they associated with the practices of the Second Empire. The Commune allowed a new social order to bloom, as men and women took on new roles and defended the city against the forces of the French army. This island of urban liberty was a reality for 73 days, reinforcing the strength of those who proselytised for social revolution, and giving Réclus the opportunity to test his ideas out in practice.

In the street battles that ended the Commune, however, 25,000 men and women were killed and Réclus, like many others, was imprisoned and then exiled to Switzerland. There, he began to write geography books and travel guides alongside anarchist pamphlets, cementing his role in the international movement. Between 1876 and 1894 he published the 19-volume La Nouvelle Géographie Universelle (New Universal Geography), and between 1905 and 1908 the smaller, 6-volume, L’Homme et la Terre (Man and Earth). These detailed, comprehensive, geography texts sought to integrate different sources of information about each part of the globe, and politically they were designed to show how the world’s resources could be distributed to improve social wellbeing. Moreover, by challenging those of his profession who colluded with the imperialist carve-up of what is now the developing world, Réclus sought to use geography as a means to improve understanding, and empathy, across borders – eroding the power of the imperialist state by fostering a universal humanitarian spirit between the peoples of each nation and territory. In language which echoes the environmental concerns of our age, Réclus looked at the ways in which people could live in harmony with each other, and in a sustained relationship with the natural world (which he referred to as equilibrium). This holistic approach was later sidelined by other approaches to regional geography, but the themes of his work remain remarkably resonant in the contemporary world.

Réclus moved to Brussels for the last 11 years of his life where he took part in founding the New University, establishing a Geographical Institute there in 1898. Here, he did some unpaid tutoring and lecturing work, continuing with his research and writing from which he supported his family. He died in 1905.

Sources: Dunbar, 1978, 1981; Fleming, 1988

The key tenets of anarchist thought

It would be misleading to offer a neat definition of anarchism, since by its very nature it is anti-dogmatic. It does not offer a fixed body of doctrine based on one particular world-view. It is a complex and subtle philosophy, embracing many different currents of thought and strategy. Indeed, anarchism is like a river with many currents and eddies, constantly changing and being refreshed by new surges but always moving towards the wide ocean of freedom. (Marshall, 1993: 3)

At the risk of funnelling the currents and eddies of anarchism into too narrow a channel, anarchists can be characterised by their opposition to all authority and their desire for a new social order. Authority, as embodied in institutions such as the church, state, army, factory and family, is argued to restrict human creativity and development, while upholding select social interests. Anarchists have sought to dispense with all such centralised and hierarchical power and have proposed living in small-scale, self-governing communities where decision making is shared (for a good introduction, see Harper, 1987). In this brief introduction to anarchist ideas we look at each part of this equation in turn.

Anti-authoritarianism

When we ask for the abolition of the State and its organs we are always told that we dream of a society composed of men better than they are in reality. But no; a thousand times, no. All we ask is that men should not be made worse than they are by such institutions! (Kropotkin, from Anarchism: Its philosophy and ideal, 1970: 134)

Anarchists believe that centralised, hierarchical institutions play an enormous role in shaping the way people think and behave. By centralising decision making and taking control away from ordinary people, such institutions are argued to stifle the ability of people to think and act for themselves (so, for example, the officers of the local and national state are appointed or elected to take on responsibility for planning, development and environmental protection for you – taking away local control). Indeed, for writers such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Oscar Wilde, society can only advance when people feel able to question authority and tradition, making their own decisions and taking their own course through life:

The more ignorant man is, the more obedient he is, and the more absolute confidence in his guide … At the moment that man inquires into the motives which govern the will of his sovereign, – at that moment man revolts. If he obeys no longer because the king commands, but because the king demonstrates the wisdom of his commands, it may be said that henceforth he will recognise no authority, and that he has become his own king. (Proudhon, from Property is Theft [1840], quoted in Woodcock, 1977: 65)

Disobedience, in the eyes of anyone who has read history, is man’s original virtue. It is through disobedience that progress has been made, through disobedience and through rebellion. (Wilde, from The Soul of Man Under Socialism [1891], quoted in Woodcock, 1977: 72; see Chapter 4 for more on Oscar Wilde)

Anarchists suggest that a hierarchical society in which some people have power and authority over others is rather primitive, restricting the scope of the mental and creative activity of its subjects or citizens. Indeed, many anarchists have argued that such social hierarchy and differentials of power interfere with the ‘natural social order’ of human society in which people would choose to freely interact in creative co-operation with one another. In his theory of mutual aid, for e...