![]()

UNIT 1 | FOUNDATION UNIT Chapter 1: Reasoned argument | 1 |

By the end of this chapter you should:

Understand the difference between an everyday argument and a reasoned argument.

Have a basic understanding of the terms ‘premise’, ‘inference’, ‘persuasion’ and their roles.

Understand what reasoning indicators are and how they help us to identify when reasoned argument is taking place.

Be able to tell apart arguments from explanations.

Understand what a dialogue is and be able to identify its key features – arguments, counter-arguments, examples, the use of critical questioning and refutation.

Understand what an ‘embedded’ argument is and be able to ‘extract’ an embedded argument in order to treat it as an argument in its own right.

REASONED ARGUMENT

The most important skill you will need to use for critical thinking purposes will be the ability to recognise when reasoned argument is taking place, and, conversely, when it isn’t. The first question we need to ask then is: what do we mean by ‘reasoned argument’? In everyday life, an ‘argument’ often refers to a squabble or spat, usually won by the person with the loudest or most persistent voice, as the following tongue-in-cheek example should make clear:

Monty Python’s argument clinic

Come in.

Ah, is this the right room for an argument?

I told you once.

No you haven’t.

Yes I have …

[this continues]

Oh, I’m sorry, just one moment. Is this a five-minute argument or the full half hour?

The way critical thinkers understand the term, needless to say, is quite different from this! For critical thinking purposes, an argument is a piece of reasoning that attempts to persuade the thinker of something. In order to do this, it uses reasons (sometimes called ‘premises’ or ‘grounds’) which lead to a conclusion. The conclusion of an argument is what an argument is trying to get us to accept and the reasons provide us with grounds for why we should accept it. The following example, taken from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s ‘Hound of the Baskervilles’, should make this clear:

argument – A persuasive piece of reasoning formed of reasons (premises) and a conclusion.

reason – A reason (sometimes referred to as a premise) provides grounds for why we should accept (be persuaded of) the conclusion of an argument.

conclusion – The conclusion of an argument is the point an argument is trying to get us to accept.

Premise 1: Guard dogs bark at strangers.

Premise 2: On the night that Sir Charles was murdered, the guard dogs did not bark.

Conclusion: Sir Charles cannot have been murdered by a stranger.

This is an example of an argument insofar as the reasons provided in premises 1 and 2 provide persuasive grounds for accepting Holmes’ conclusion that whoever murdered Sir Charles must have been known to him.

Arguments can be simple, where only one premise is used to persuade us of a conclusion:

Premise: John is a werewolf!

Conclusion: Therefore it is unsafe to go out with him on the night of a full moon!

Or more complex, where a number of premises are used:

Premise 1: Mars is a cold and inhospitable planet with temperatures dropping to minus 130° centigrade.

Premise 2: Despite several spacecraft having landed on the planet, there is no photographic evidence to suggest that it supports life.

Premise 3: Nor have we had any ‘extraterrestrial’ response to the radio signals we have been sending to this planet for many years now.

Premise 4: And even if life had the potential to form, the amount of meteor showers experienced by the planet would wipe it out in its first stages.

Conclusion: We can safely conclude that there is no such thing as life on Mars.

So long as a piece of reasoning provides us with at least one premise and a persuasive conclusion that follows from this, then it can be regarded as an argument.

It is important to remember, however, that not all pieces of reasoning attempt to persuade and, conversely, not all acts of persuasion involve reasoning. Because of this, the following example, relating to the aim of this book, is not a genuine argument and it is important that we understand why:

Critical Thinking aims to:

• develop skills and encourage attitudes which complement other studies across the curriculum

• prepare candidates for the academic and intellectual demands of higher education, as well as future employment and general living

• introduce concepts, terms and techniques that will enable candidates to reflect more constructively on their own and others’ reasoning. (AQA specification)

Here we have a set of possible reasons for why we ought to study critical thinking, but no conclusion persuading us that we should do so. As such, this example is not an argument. It is only once we supply this missing material – i.e. ‘if you value these skills, then you should take a course in critical thinking’ – that an argument is formed.

Turning this point on its head, look at the following examples:

Each of these examples tries to persuade us of something, i.e.:

• We should donate money to charity.

• We need to become more energy efficient.

• We ought to purchase a particular brand of a product.

But they lack reasons telling us why we should be persuaded. It is only once we supply at least one supporting reason for each conclusion that an argument is created. For example:

• Innocent children are dying of starvation, therefore …

• Increasing temperatures caused by the burning of fossil fuels are endangering the future of our planet, therefore …

• Brand X is better quality than any of its rivals, therefore …

The essential features of an argument then are: (1) it must have at least one premise (reason) and a conclusion and (2) its conclusion must be persuasive, and the reasons must provide us with grounds for being persuaded. If either of these elements is missing, the example is not an argument, at least not in the technical sense. The simplest way of deciding whether or not a piece of reasoning presents us with an argument then is to ask the questions: ‘Is this trying to get me to accept something?’ and ‘Does it provide reasons for why I ought to accept it?’ If the answer to both of these questions is ‘yes’, you are dealing with an argument. If ‘no’, then you are not. It’s that simple!

If a piece of reasoning includes a persuasive inference and at least one premise/reason offering grounds for why you should be persuaded, then it is an argument. If either of these is lacking, it won’t be.

If the questions are answered in the positive and you are happy that you are dealing with an argument, the next two questions you need to consider are, firstly: ‘What, in plain English, is this trying to get me to accept?’ and secondly: ‘What reasons does it provide in order to do this?’ The first question will allow you to identify the argument’s conclusion, the second, the premises used to support it.

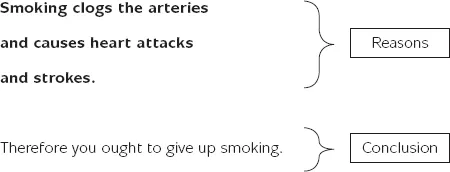

Applying these points to an example should make this clear:

To locate the conclusion of an argument, you will need to identify the point it is trying to get you to accept. To locate the reasons, you will need to identify the grounds it provides for why you should accept it.

Taken as a whole, this example is persuasive and provides grounds for my being persuaded and can thus be regarded as an argument. It is trying to get me (the smoker) to stop smoking (conclusion) and the reasons it uses to do this are: (1) it clogs arteries and (2) it causes heart attacks and strokes. Note how the order ...