- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stress and Coping Across Development

About this book

This is the second volume based on the annual University of Miami Symposia on Stress and Coping. The present volume is focused on some representative stresses and coping mechanisms that occur during different stages of development including infancy, childhood, and adulthood. Accordingly, the volume is divided into three sections for those three stages.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

I

Infancy

1

Maternal Deprivation and Supplemental Stimulation

Duke University Medical School

University of Miami Medical School

Development in mammals is profoundly affected by environmental stimuli. Those stimuli provided by the mother appear to be most critical for survival and growth. Disruption of the mother-infant relationship contributes to marked behavioral and physiological stress responses in the offspring ranging from transient changes in body temperature, heart rate, and locomotor activity following short periods of separation, to marked growth retardation, developmental delays, and immune dysfunction following more long-term separations (Field, 1985; Field & Reite, 1984; Harlow & Zimmerman, 1959; Hinde & Spencer-Booth, 1971; Hofer, 1984; Levine & Coe, 1985; Reite, Short, Seiler, & Pauley, 1981; Suomi, Collins, & Harlow, 1976). A number of studies demonstrate that specific sensory cues from the mother induce different physiological and behavioral responses in young animals. For example, nipple attachment in rats is promoted by specific organic substances on the ventral surface of the mother, and thermal input from the mother modulates locomotor activity in weanling-age rat pups, while compounds secreted by the mother’s GI tract “orient” pups to the nest (Compton, Koch, & Arnold, 1977; Leon & Moltz, 1971, 1972, 1973).

More recent studies by our group suggest that mother-pup interactions also have marked effects on biochemical processes in the developing pup (Schanberg, Evoniuk, & Kuhn, 1984). These biochemical processes, like behavior, respond to specific environmental cues suggesting that mother-pup interactions are important regulators of physiological as well as behavioral functions. Sensory stimuli associated with the mother elicit coordinated physiological and biochemical responses which vary with the nature of the stimulus. Whereas some environmental stimuli are important regulators of growth and development, others subserve quite different functions, such as maintaining tissue sensitivity to specific hormones.

Although studies on human infants are less definitive, growth failure and developmental delays are characteristic problems of human infants deprived of stimulation as, for example, the premature neonate and the nonorganic failure-to-thrive infant (reactive attachment disorder). Inadequate stimulation has been implicated as a potential stressor and contributor to the delays in both of these groups. Previous attempts to facilitate their growth and development have yielded inconclusive data. However, recent research by our group suggests that supplemental stimulation contributes to weight gain and sleep/wake behavioral organization in these infants (Field, Schanberg, Scafidi, Bauer, Vega-Lahr, Garcia, Nystrom, & Kuhn, 1986; Goldstein & Field, 1985).

The first group of studies we discuss are those demonstrating that active tactile stimulation of preweanling rat pups by the mother provides specific sensory cues that maintain normal growth and development. The data presented demonstrate that restriction of active tactile stimulation by the mother during maternal separation produces at least three different alterations in biochemical processes involved in the growth and development of the rat pups. These alterations can be reversed by providing supplemental stimulation. The second group of studies we review document the facilitative effects of supplemental stimulation on the growth and behavioral organization of preterm intensive care neonates and nonorganic failure to thrive infants.

Maternal Separation Stress, Tactile Stimulation, and Growth in Rat Pups

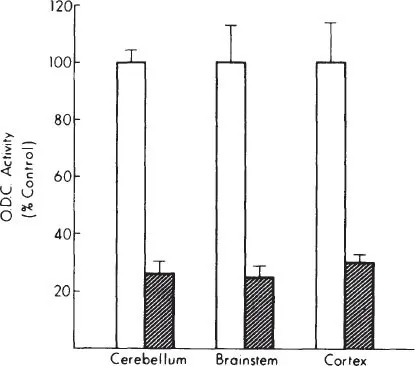

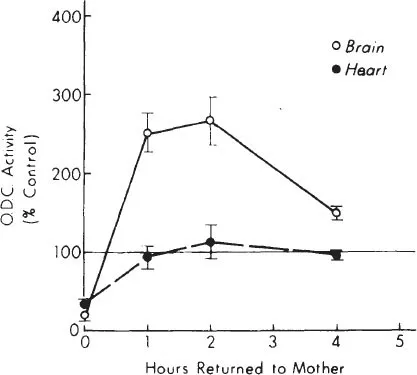

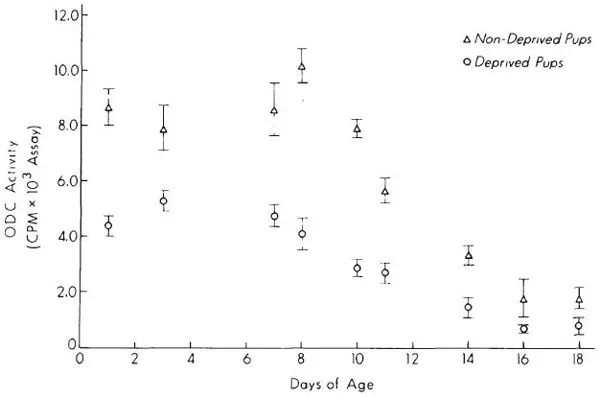

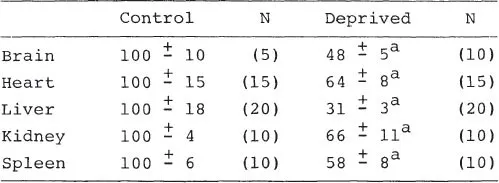

Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), the first enzyme in the synthesis of the polyamines putrescine, spermine, and spermidine, is an important regulator of growth and differentiation that is affected by mother-pup interactions. The end products of this enzyme are intimately involved in the regulation of protein and nucleic acid synthesis (Bachrach, 1973; Raina & Janne, 1970), and activity of this enzyme is thought to be a sensitive index of environmental effects on biochemical and physiological processes in the developing animal. While ODC activity in both neonatal and adult rats responds markedly to various stresses, the pattern of tissue response is determined by the nature of the environmental stimulus, or stress. Separation of preweanling rat pups from the mother (maternal deprivation), is one stress that profoundly affects tissue polyamine systems in developing animals. Maternal deprivation causes an immediate and marked decrease in tissue ODC activity and in tissue putrescine concentration. These changes occur in all tissues that we have studied including brain, liver, heart, kidney, and spleen, and in all brain regions (Fig. 1.1, Table 1.1). ODC activity normalizes soon after rat pups are returned to the mother (Fig. 1.2). This marked effect of maternal deprivation is observed in preweanling pups, from postnatal Days 1 to 18 (Fig. 1.3). It then rapidly disappears over the next few days.

Fig. 1.1. Effect of maternal deprivation on ODC activity in different regions of 10-day-old rat brain. All values are expressed as means ± SEM. All differences are significant P < 0.05 or better.

Fig. 1.2. Comparison in 10-day-old rat brain and heart of the recovery of ODC activity after a 2-hr deprivation and return to the mother. All values expressed as means ± SEM. N = 5 in each group. Brain and heart values are significantly below control (P < 0.05) at 2 hr. Brain values are significantly above control values at each point after return (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.3. Effect of a 2-hr maternal deprivation on preweanling rat brain ODC activity in pups of different ages. All values are expressed as means ± SEM. N = 5 in each group. All differences significant P < 0.05 or better.

Table 1.1

Effect of Maternal Deprivation on ODC Activity in Organs of 8 Day Old Rats

Effect of Maternal Deprivation on ODC Activity in Organs of 8 Day Old Rats

Pups were maternally deprived and killed 2 hours later. Results are expressed as percentages of control ± sem.

ap <.05 or better relative to control.

The decline in ODC associated with maternal deprivation does not result from a change in body temperature, exposure to an unfamiliar environment, or other nonmaternal stimuli (Butler & Schanberg, 1977). Similarly, interruption of feeding does not mediate the fall in ODC, inasmuch as preweanling rat pups placed with a mother whose nipples have been ligated do not experience a similar decrease of ODC activity in all tissues. The latter demonstration is extremely important, given that feeding is one of the major components of the mother-pup interaction during the first 2 postnatal weeks, with pups feeding an average of every 10 min (Lincoln & Wakerly, 1974). Furthermore, auditory, visual, and olfactory stimulation, which play a role in mother-pup interaction at various times during the development of preweanling rats, do not influence ODC activity (Kuhn & Schanberg, unpublished observations). Apparently those stimulus modalities are not involved in the ODC response of preweanling rats to maternal deprivation. This is not surprising in that both the auditory and visual systems are not functional at birth, but mature during the first 2 to 3 weeks postpartum.

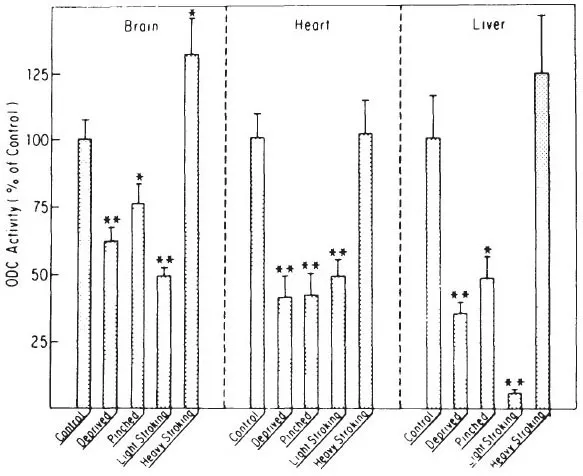

Interruption of active tactile interaction between mother and pup seems to trigger the decline in ODC activity during maternal separation. Placing pups with a mother rat that has been anesthetized (with urethane) to prevent active interaction but not feeding (Lincoln & Wakerly, 1974) changes tissue ODC activity in the same way that separating the pups from the mother alters ODC activity (Table 1.1). This finding is striking, as the decrease in ODC activity occurs despite the presence of many other sensory cues that are passively transferred by the mother (olfactory, gustatory, auditory, tactile, etc.) and actively emitted by the littermates. Furthermore, when deprived pups are given tactile stimulation grossly approximating that of maternal grooming (i.e., paint brush stroking simulating maternal licking motions) ODC activity returns to normal levels in all tissues, although other forms of sensory stimulation of equal intensity are ineffective (Figs. 1.4 and 1.5). This finding is of particular interest because tactile stimulation appears to be an important stimulus for growth and development in a number of species, including humans (cf. Cornell & Gottfried, 1976; Field, 1980; Schaeffer, Hatcher & Barglow, 1980 for reviews).

Fig. 1.4. Pups were maternally deprived for 2 hours and either left untouched or stroked heavily, stroked lightly, or pinched as described in Methods and then killed. Controls were left undisturbed with the mother for 2 hours. Results are expressed as percent control ± SEM. Control ODC activity = 0.147, 0.188 and 0.048 nmoles ornithine/g tissue/hour respectively for brain, heart and liver.* = p < .05 or better compared to controls.** = p < .001 or better compared to controls, n ≥ 15 except pinched and light stroking n ≥ 8.

Fig. 1.5. Pups were maternally deprived and stimulated as described in Fig. 1. Results are expressed as percent control ± SEM. Control serum GH = 54 ng/ml.* = p < .002 or better compared to controls, n ≥ 15 except pinched and light stroking n ≥ 10.

The physiologic signal which triggers the decline in ODC activity following interruption of maternal-pup interaction is still unknown. The uniform decline in tissue ODC activity throughout the body suggests that some general endocrine or metabolic response to the withdrawal of maternal tactile stimulation mediates this fall. This hypothesis is strengthened by our finding that ODC decreases during maternal deprivation even when innervation of peripheral tissues is not yet functional, or when innervation is blocked pharmacologically with propranolol or atropine (Butler, Suskind, & Schanberg, 1977; Schanberg, unpublished observations). ODC activity is such an accurate and sensitive index of cell growth and development that its decline during maternal deprivation could represent a specific biochemical mechanism through which environmental stimuli affect growth and development.

The change in ODC activity during maternal deprivation suggested that secretion of one or more of the many hormonal regulators of ODC was affected by this stress. In additional studies, we have shown that maternal deprivation elicits a marked and unusual neuroendocrine response. This response represents the second mechanism controlling growth and development that is disrupted by maternal deprivation. When preweanling rat pups are separated from the mother, there is an increase in corticosterone and a selective decrease in growth hormone secretion from the anterior pituitary, while serum levels of other stress-responsive hormones including prolactin and TSH do not change if nutrition and other aspects of the environment are controlled, minimizing disruptive conditions. This selective decrease in growth hormone is somewhat unique as stress almost always elicits a complex pattern of endocrine responses which in the rat usually involves decreased growth hormone and TSH and increased corticosterone and prolactin secretion. The inhibition of growth hormone secretion during maternal deprivation could affect development significantly over a prolonged period of deprivation, as circulating growth hormone is responsible for the generation of substances called somatomedins, which are among the major regulators of muscle and possibly organ growth.

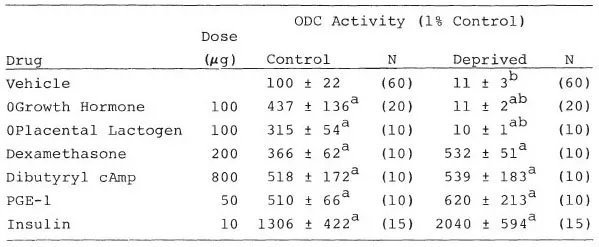

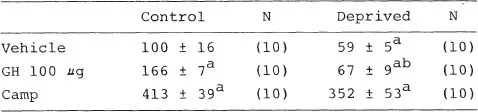

Growth hormone is a well-known regulator of ODC activity in brain as well as in peripheral tissues (Roger, Schanberg, & Fellows, 1974). Therefore, the finding that growth hormone secretion decreased during maternal deprivation provided a possible explanation for the fall in tissue ODC activity. To investigate this possibility, we injected pups with ovine growth hormone during the separation procedure to reverse the decrease in ODC activity. Rather than restoring ODC activity to normal levels, as predicted, we found that tissue ODC was completely and selectively unresponsive to growth hormone during maternal deprivation. Growth hormone was unable to induce ODC activity in liver or brain of deprived rats, although a number of other hormones including cyclic AMP, insulin, and the glucocorticoid hormone dexamethasone still would induce ODC activity normally (Tables 1.2, 1.3). This selective loss of tissue response to growth hormone represents the third major defect in growth-regulating processes that is disrupted by maternal deprivation.

Table 1.2

Effect of Hormones on Liver ODC Activity in Maternally Deprived Rat Pups

Effect of Hormones on Liver ODC Activity in Maternally Deprived Rat Pups

Pups were maternally deprived for 2 hours, injected SC with vehicle or hormone, and killed 4 hours later. Results expressed as percentage of control ± sem. control ODC activity was 37 nCi/30 min/g tissue.

ap < 0.05 or better relative to vehicle treated control.

bp < 0.001 relative to paired control.

Table 1.3

Effect of Hormones on Brain ODC Activity in Maternally Deprived Rat Pups

Effect of Hormones on Brain ODC Activity in Maternally Deprived Rat Pups

Pups were maternally deprived for 2 hours, injected intracisternally with saline, GH or cAMP, returned to the deprivation cages and killed 4 hours later. Control pups left with the mother were injected at the same time. Results are expressed as % control ± sem. Control ODC activity was 40 nCi/30 min/g tissue.

ap < .01 or less relative to vehicle-treated control.

bp < .001 relative to GH-injected control.

These three effects of maternal deprivation (decrease in tissue ODC activity, fall in growth hormone secretion, and loss of tissue sensitivity to exogenous growth hormone) appear to be regulated by the same sensory stimulus: active tactile stimulation by the mother. Therefore, placing the pups with a urethane-anesthetized mother to eliminate maternal tactile stimulation of the pups, while ma...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Part I: Infancy

- Part II: Childhood

- Part III: Adulthood

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Stress and Coping Across Development by Tiffany M. Field,Philip Mccabe,Neil Schneiderman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.