![]()

Part I

Solar and Diffusion Theory

![]()

1

Solar in Emerging Markets

Vast swathes of humanity live without any electricity at all. This demands that they seek out far less convenient and more expensive substitutes, with harmful impacts on their health and well-being, and often go without the appliances, services and other benefits that many of us take for granted. And yet the vast majority of this population lives in the ‘sunbelt’, 30 degrees north or south of the equator, where sunlight is the strongest on the planet and where the sun generates more watts of power per square metre than anywhere else. So why is there any electricity shortage whatsoever?

The technology to tap into the sun’s energy and generate electric power – solar photovoltaic technology – has existed in its present form for more than half a century. Of late, this technology has faced a surge in demand. But the irony is that this growth is not coming from the sun-soaked emerging markets, but from the relatively more cloudy industrialized countries.

Solar photovoltaic technology was proactively introduced into many emerging markets in the early 1980s. This was done with much fanfare, hope and promise for the dawning of a new solar era, replete with independent, reliable, renewable energy from the sun. The reality, however, was that its uptake was disappointingly slow. By the turn of the century, just 1 million households in emerging markets were estimated to be using a solar system for electricity – accounting for no more than 0.25 per cent of unelectrified households globally.

But just at the point when many were tempted to give up on solar, some emerging markets turned the corner. So much so that by the end of 2007, more than 7 per cent of the unelectrified households in a country like Sri Lanka were using a solar system. And Sri Lanka was not alone: parts of India, Bangladesh and China also saw a rapid acceleration in the diffusion of solar during the same period. Why was this? Why had such a promising technology been so slow to diffuse throughout the 1980s and 1990s? And why, just at the time when people were starting to lose faith, did it reach a tipping point and rapidly diffuse to thousands of users in select emerging markets? These are the questions that Selling Solar sets out to answer.

No Electricity: An Entry Point for Solar

As hard as it may be to imagine, not long ago the entire world lived without electricity. Without power, the most essential need in the home was light – to be able to see between sunset and sunrise. In order to meet this challenge, the pre-electrified world tried several different methods – candles, followed by whale oil, followed by kerosene.1 But none of these could compete with the ease and convenience of electric light at the flip of a switch. And so when grid electricity arrived in rural America, communities were said to hold a mock funeral for their kerosene lanterns, during which lanterns were buried while the local boy scouts played taps. Indeed, an American farmer from the 1920s probably best captured the taste for electricity when he said at a Sunday gathering:

Brothers and sisters, I want to tell you this. The greatest thing on Earth is to have the love of God in your heart, and the next greatest thing is to have electricity in your house.2

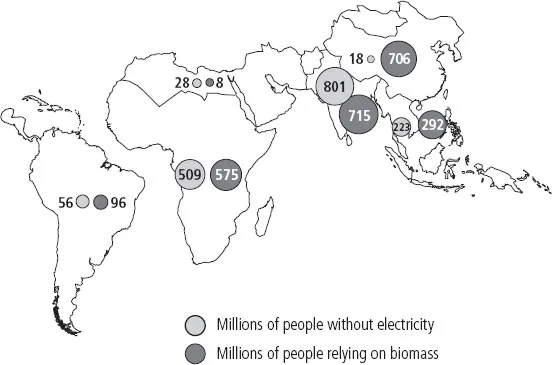

Today almost all inhabitants of industrialized countries have the convenience of grid electricity. But for the inhabitants of many emerging markets, it is a very different experience. The number of people without electricity is estimated at 1.64 billion – more than five times the population of the US, or 27 per cent of the world’s population – and of this, four out of five households are in rural areas.3 The problem remains particularly acute in South and Southeast Asia, where the number is more than 1 billion, and in sub-Saharan Africa, where it is roughly 500 million people. And this does not include the many, many more people who have a connection to the national electricity grid but who suffer chronic, unscheduled blackouts. Indeed, when the author asked a farmer in South India how often he experienced power cuts, the farmer quickly shot back, ‘Better you ask me how often I have any power at all.’

It is not that governments in emerging markets have not had bold ambitions. The Sri Lankan Government would not have been alone in using slogans like ‘Electricity for All by 2000’;4 nor would it have been alone in missing the target. But the fact of the matter is that extending the national grid to remote and dispersed rural households, which initially have very low electricity demand, is a costly affair. In areas such as western China, the Amazon or the Himalayan foothills, the cost of a rural connection can be seven times that in the cities.5 On this basis some have even concluded that complete grid electrification in many emerging markets is, and always will be, too expensive.6

When faced with these high costs, governments have tried more decentralized approaches, such as setting up village-scale electricity grids powered by diesel generators. This is where a local distribution grid connects all the homes and small enterprises in the village, and diesel fuel is brought in the usually long distances to power a generator at fixed times each day. Not surprisingly, due to the remote location of these systems, the electricity provided tends to be both unreliable and expensive, and thus it has not provided an ultimate solution for emerging market governments in their campaigns to bring electric power to their citizenry.7

Figure 1.1 Millions without electricity and relying on biomass for cooking

Source: IEA (2002), p12

Of course, in the absence of a solution from their government, people don’t just give up and sit around in the darkness without any entertainment or other comforts:

The world outside the electricity grid is far from one of passive energy deprivation. There is rather a complex and dynamic evolution of energy demands with time, economic development, fashion and rising aspirations. These demands are met by local entrepreneurs and traders, responding often with considerable ingenuity and initiative to the changes taking place in the energy market.8

In almost every unelectrified village you can find a local trade in kerosene and kerosene lanterns for lighting, car batteries and battery-charging stations for black and white TV, dry cell batteries for radios, and, for the few who can afford it, diesel fuel and diesel generator sets for powering most modern appliances. Travelling around these areas you will often see someone carrying home a bottle of kerosene from the local shop, or a battery strapped to the back of a bicycle, being rolled to the nearest charging station several kilometres away. People want the benefits that electricity can bring and will go out of their way, and spend relatively large amounts of their income, to get it.

Figure 1.2 Carrying home kerosene fuel

Figure 1.3 Transporting a battery to nearest grid point for charging

Figure 1.4 Typical battery-charging station in village

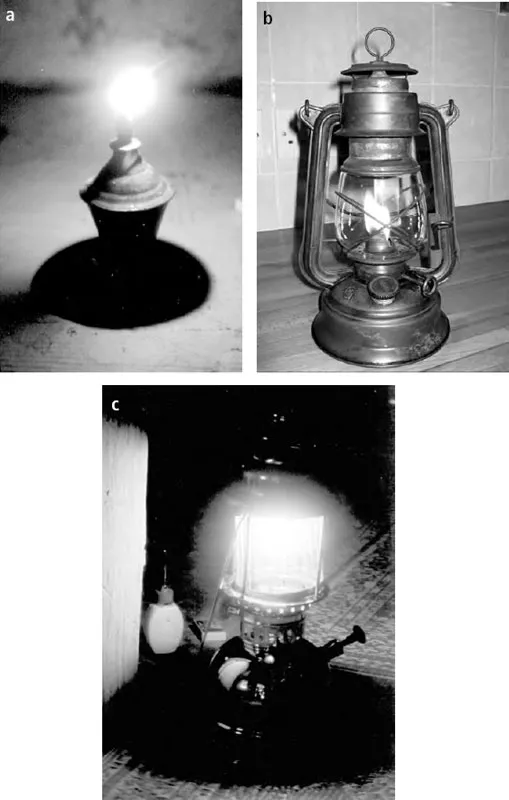

While we can admire the resilience and resourcefulness of local populations in the face of no electricity, the fact is the products they are forced to use remain far from ideal. Kerosene, for example, brings with it a severe fire risk. It is so easy for a kerosene lantern to be knocked over and burn down the entire house of an already poor family. It also produces a dim light, making it hard to do schoolwork or housework at night, and, of course, it produces noxious fumes. Combine this with the inconvenience of having to go to buy the fuel, store the fuel and light the fuel, and you have a pretty unpopular product. Equally, there is no great love for diesel generators. In the absence of a reliable electricity grid, generators are being bought in ever-increasing numbers in emerging markets.9 But generators create noise and air pollution, and also entail certain fire risks. Not to mention the hassle of procuring the fuel, storing the fuel, pouring the fuel and maintaining the generator set, which, because it has many moving parts, needs regular upkeep. And this says nothing about the lifetime costs of running one, since diesel fuel always costs more in rural areas than in the cities, and generally goes up in price, not down.

Figure 1.5 Different types of kerosene lantern: (a) wick lantern, (b) hurricane lantern, (c) Petromax lantern

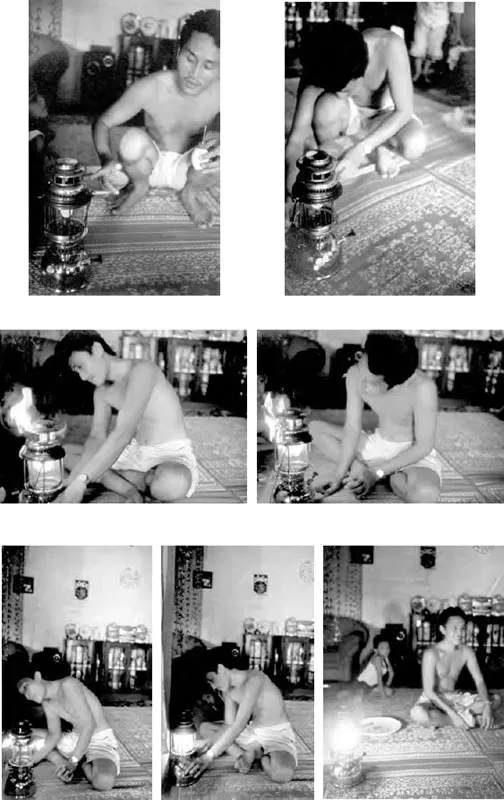

Figure 1.6 The process of lighting a Petromax lantern

Figure 1.7 A typical diesel generator

Without an electricity grid and with a choice of pretty unpopular options, it is not surprising that solar technology has entered the rural energy mix.10 Solar technology makes use of a resource – sunlight – that is truly everywhere, so it can produce electricity without transporting fuels, such as kerosene or diesel, to site. Moreover, it offers electricity, and light, at the flip of a switch, entails relatively little maintenance, has no harmful emissions and, once paid for, does not have much in the way of recurring costs. We can easily see why people had high hopes for this technology when it was first introduced into emerging markets.

Rural Solar Applications

At first, aid agencies tried to put solar to work for unelectrifed populations. In some projects, these agencies tried an approach that would have seemed intuitive at the time – they centralized the solar panels in the middle of a village, or on its outskirts, strung distribution wires to each home, and then transported the solar power to the local families or enterprises. This has since come to be known as a solar ‘mini-grid’, and its track record in terms of sustainability and cost-effectiveness is not a good one.

Figure 1.8 A solar mini-grid

Pakistan was one of the first countries to experiment with solar mini-grids, setting them up in eight villages in the late 1980s. However, the project failed on two counts. First, it failed in terms of maintenance: if the system is owned and used by a village, who precisely is responsible for its upkeep and for ensuring that everyone uses only their appropriate share of the power? Second, it failed in terms of cost-effectiveness: if the poles and wires to transport electricity and connect the households is the most costly part of rural electrification, then why use them with solar if you don’t have to? Faced with these difficult question, the Pakistan post-evaluation study by the World Bank and UNDP concluded categorically that:

a decentralized approach for household PV systems in which individual households or buildings are powered by individual PV systems is less costly than a centralized approach in which a village is serviced by a single PV array and mini-distribution grid.11

A more decentralized approach to using solar technology has come to be known as the ‘solar home system’. This approach puts the ownership of the system and the respon...