Chapter 1

Arts Integration What Is It and Why Do It?

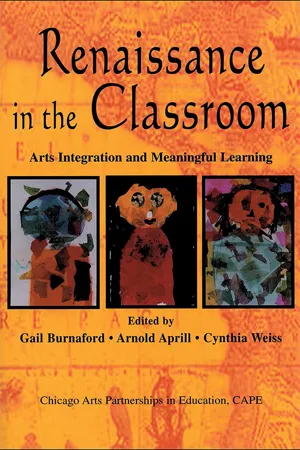

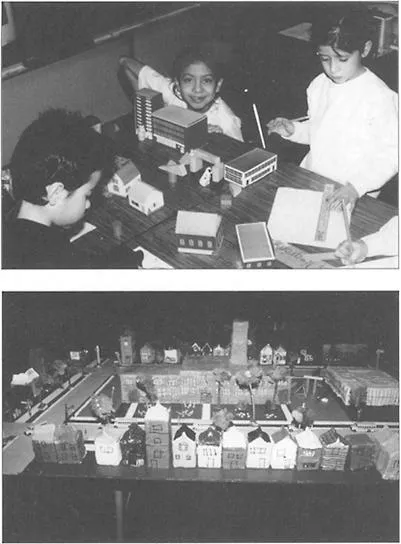

Second-grade students at Pulaski Elementary had been studying ecology. They used recycled milk cartons to create a scale model of their school and its surrounding neighborhood. The students photographed actual homes in the area, reproduced accurate scale models, and designed communities on the computer program, “Sim City.” Because the neighborhood is being gentrified, the homes were changing during the course of the project. This led to lengthy discussions about neighborhood planning and how to create communities that were the right scale for children. The project culminated in the presentation of the scale model to the principal and a discussion about the need for a school playground. Six months later, the school did indeed build a playground. (See photos)

p p f f f

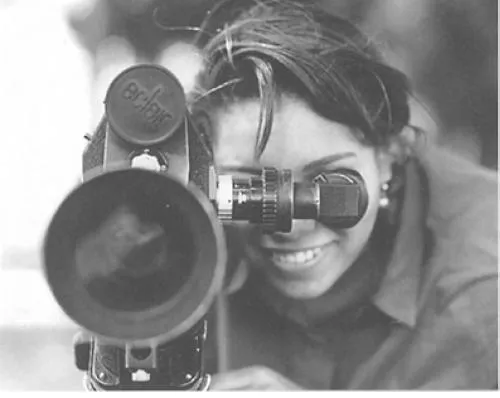

Sophomores, juniors, and seniors in the Metro Program at Crane High School worked with filmmakers and video artists from the Community Film Workshop to dissect characters on TV. They analyzed African-American stereotypes in the media- examined what messages an image communicates through point of view, framing, lighting, focus, and color, determined their own messages-, and then created their own story boards for filming. (See photo)

p p f f f

Third graders at Murray Language Academy studied birds, but they did much more than that. They took part in a multidimensional learning process that consisted of experiments (e.g., “What is inside an uncooked chicken egg?”); movement, dance, and role-playing (e.g., moving like penguins and eagles); origami and other visual arts-, a visit to the zoo; research on migration patterns; reading both fiction and nonfiction books dealing with birds; and descriptive writing. Using the knowledge they gained through this multi faceted curriculum, the students created original illustrations of birds that were then laminated for bookmarks.

How is learning happening in each of the classrooms and schools described in these vignettes? How are children engaged? What seems to be the role of curiosity and imagination in each of these classroom stories? In other words, what’s going on here?

Carol Navarro’s second grade students at Pulaski Community Academy build a scale model of their community in a lesson that integrates math, social studies, and sculpture.

Photo: Cynthia Weiss

The Community Film Workshop teaches students how to view the world through a camera at Metro/Crane High School.

Photo: Jim Taylor, Community Film Workshop

For starters, each of these classrooms, as part of the Chicago Arts Partnerships in Education (CAPE) network, has access to painters, dancers, musicians, filmmakers, videographers, and others who think about the world as artists do. They also have day-to-day access to teachers who think creatively about how learning in their classrooms can go beyond the textbook and dip right into the real world. These teachers and the artists who work with them have been engaging in arts integration. These teachers believe that children not only need the arts in their daily lives, but also can benefit from arts learning that is deeply immersed in other curricular areas.

The teachers in those classroom stories are faced with the same challenge of meeting state goals and district standards as other teachers throughout the country. They are held accountable for students’ test scores on a regular basis, and they feel the pressure of time to cover everything that a child should know by the time he or she moves on to the next grade level. Yet they have seen firsthand that none of those external goals can happen unless children participate actively, use their hands as well as their minds, and make connections between what they are learning and what they are living. These teachers see arts integration as one avenue for making these laudable goals into practical realities.

This chapter introduces the idea of integration as many of the teachers and artists in the CAPE network have come to know it. We describe how arts integration is embedded in the larger context of curriculum integration, which has a history in the field of education. The chapter also explores how arts integration is compatible with other engaged learning strategies such as problem-based learning and teaching with awareness of the multiple intelligences. Arts integration is not an island; this approach builds on the work of many other initiatives dedicated to making schooling more rigorous, real, and creative for young people.

Arts integration is a way of thinking about learning and teaching; it is not a formula, and it is not a strict structure that requires specific resources. Arts integration encourages individuals and groups of school people to stretch out a hand to community resources, whatever they may be, and make connections to the school curriculum. It encourages leaders of young learners to transfer knowledge from one area to another and to make connections between a unit in mathematics and a unit in social studies, or between a unit in science and a unit in language arts. This process shows students that such thinking is possible and actually done in the real world. That is what arts integration is all about.

CURRICULUM INTEGRATION: HISTORY AND CONTEXT

What does curriculum integration look like regardless of whether the arts are present? We felt it was important to take a step back and examine that question because arts integration is a process that is not unconnected to a larger framework and history in which teachers have looked for connections across processes and content.

As the vignettes at the opening of this chapter illustrate, curriculum integration often involves a structured inquiry process that encourages finding problems and asking questions. Students work from what they know and what they want to know, and they develop complex means to represent and present what they are learning. Even second graders can build a neighborhood architectural plan. The learning that they produce typically has value beyond their lives in classrooms; real-world people engage in that learning, see the performances, and share in many of the products that students develop. Then there is conscious and extensive reflection that helps adults and young learners figure out what they did and what it means during the arts integration experience. In other words, curriculum integration is a conscious negotiation between the learner and the community ; it involves questions of personal meaning for the learner and questions of social responsibility for the learner as a citizen of the planet.

The history of curriculum integration suggests that we are talking about much more than simply joining one piece of content with another. Integration of content is really more of an educational philosophy than it is an instrument for doing something in the classroom. Jim Beane (1997) is an educator who has written and thought much about the meaning and purpose of curriculum integration in general. He noted that curriculum integration, when it is seen as a core precept of democratic education, “seeks connections in all directions.”

What does that mean? Integration deepens instruction by bringing skills, media, subjects, methods, means of expression, people, concepts, and means of representation to the service of learning. Through integration, kids in schools have access to all these things. When the Civil War becomes a focus for integration, students have the opportunity to talk to real people outside the classroom about the meaning of the war; they find new ways to visually represent what the war might have meant to families in that time; they research the music that tells the tales of the war; they share their knowledge with people beyond the four walls of their classroom. Curriculum integration seeks connections in all directions.

Beane (1997) went a step further and contended that curriculum integration is really about social integration, claiming that”…teachers who use the approach make concerted efforts to create democratic communities within their classrooms” (p. 65). Arts integration classrooms also value this notion of democratic communities. The arts bring people together to work toward common goals and express key concepts and beliefs, as the stories in this book reveal. Integration of curriculum becomes a strategy for advocacy. Teachers and artists advocate for understanding, for knowledge across cultures, and for community building.

Curriculum integration reflects value systems about the purposes of teaching and learn- ing. This adds yet another dimension to our understanding of curriculum integration—the aspect of integrating self and social interest. Curriculum integration is a method- ology for assisting students in negotiating between their personal needs and their con- nection to the larger community. This negotiation is the basis of all meaningful learning.

The integration of two subjects—music and math, history and dance—is not an end in itself. Such connections invite integration of a continuum of skills, content, and concepts. Meaningful curriculum integration generates genuine exploration of concepts that stretch across disciplines while giving students opportunities to test their own skills (Whitin & Whitin, 1997). Integrative curriculum is more than a set of basic discrete skills that can easily be measured by standardized means. But such curriculum can engage students in learning and using those skills as they grapple with deeper concepts and themes that are not limited to one specific content field. Integration brings teachers and students together for co-teaching and co-learning. Curriculum integration is a means toward deeper instruction and meaningful learning, toward greater social understanding, and toward a more complex and more interesting view of the world.

Project-based Learning: A Link to Curriculum Integration

Throughout this book, teachers, students, and artists discuss the projects they have done through arts integration. The term project has a long history in education, not unconnected to work in the arts. In 1918, William Heard Kilpatrick introduced the project method in educational circles (Hennes, 1921; Kilpatrick, 1918). Kilpatrick believed that children would learn more if they were engaged in some purposeful activity, rather than just completing tasks for the teacher to view and assess. If students had a purpose that was real and useful in the world, according to Kilpatrick, they would learn more and feel better about themselves. They would become thinkers as well as doers.

Sound familiar? Here in the advent of the 21st century, we are still working toward approaches in schools that link student work with real tasks and authentic purposes. Oth- ers initiatives in education, such as problem-centered learning (Casey & Tucker, 1994) and project-based learning (Wolk, 1994), take their cue from Kilpatrick’s earlier methods, and so does arts integration. In all of these strategies, there are real products, with considerable input from students in the planning and conceiving of those products.

Students in project-based learning classrooms often collaboratively conceive of a question or an issue to explore. They see the inevitable links between what they are learning in school and what the community and the world have to contribute to that learning. What’s more, they see what they have to contribute back to that community and that world. Students must solve problems and use strategies that they learn to work with others. The process of conceiving, designing, and following through on a plan of action becomes critical to stu- dents’ success. As Eve Ewing, a seventh grader at Hawthorne School, put it, “Art changes people’s minds.” Action and reflection are both indicators of thoughtful integration. Art can, indeed, change people’s mind…about social issues, about solving problems, and about how school children can be active agents in their communities.

Multiple Intelligences: More Awareness of the Value of Arts in Classrooms

One familiar movement in schools today is the alignment of curriculum with multiple intelligences. Howard Gardner’s (1983) theory of multiple intelligences (MI), outlined in his book, Frames of Mind, has contributed to the increasing awareness of the value of the arts in children’s learning and in schools today. Educators such as Thomas Armstrong (1994) and David Lazear (1991), have helped translate Gardner’s theory, which is essentially a psychological framework, to the world of classroom teachers. Gardner suggested that there are at least seven intelligences that most people bring to learning. Of the seven, two (linguistic and logical/mathematical) seem to predominate in most classrooms, although many children have dominant intelligences in other domains. The theory, with respect to schooling, is that if we expanded the repertoire of teaching practices to include more attention to students’ capacities to use their musical, spatial, intrapersonal, interpersonal, and bodily/kinesthetic intelligences, we may reach more children. Building on students’ strengths through their more dominant intelligences equips them to learn more fully.

Teachers are attracted to this theory and have embraced the possibilities for their classrooms. They have attended workshops, conferences, and teacher development sessions that provide information on how these intelligences might actually be utilized as learning tools across the curriculum. As a consequence, we have seen more and more classrooms that include aspects of the arts in the curriculum.

What is the relationship between MI theory and art...