![]()

Chapter 1

The Variety of Standards

A STANDARD IS AN AGREED SET OF CHARACTERISTICS, including ways of behaving or doing something. Often the agreed way of doing something arises out of common practice — standards for technical areas like the specification of screw threads are an example. But when talking about sustainability, often standards are a way of trying to achieve common practice in an area in which it may not yet widely exist, such as the measurement of carbon dioxide emissions.

The topic of standards is complex as there are many varieties and ways of classifying and understanding them. This section takes a functional approach, asking questions such as ‘what do they do?’ and ‘how do they do it?’

Who says so?

Perhaps the most important aspect of a standard is ‘who says’ that it is a good way to do things. This governs the legitimacy of the standard.

By numbers, the majority of standards have been produced by ISO (the International Standards Organisation) or its members, the national standards bodies. There are tens of thousands of ISO standards alone, mostly covering technical activities that have been agreed principally by commercial organisations. However, there are some important ISO standards very relevant to sustainability, including ISO 14001 on environmental management systems and ISO 26000 on organisational social responsibility.

Other standards have been produced by civil society. These include many of the prominent standards for particular aspects of sustainability. Fairtrade (principally for ensuring socially acceptable standards of production) is an example.

The public sector can also produce standards. Some of these concern the operational activities of the public sector itself, while others are the result of the political process. Those standards resulting from the political process are called ‘laws’ or regulations. (Standards produced by non-state actors are therefore often described as ‘voluntary regulation’ or ‘self-regulation’.) At the international level, the laws become treaties. For sustainability, some of the most important standards include the human rights and the ILO (International Labour Organisation) conventions labour rights.

Standards can sometimes ‘move’ from one sponsor to another. Standards for organic food were originally produced by civil society but are now supported by governments. Other standards produced by civil society will incorporate elements such as labour rights within them: SA8000 on labour conditions is an example.

Given that the answer to the question ‘who says so’ governs the legitimacy of the standard, it follows that the most powerful standards, from the point of view of legitimacy, are those which have included all sectors and many different parties in their development and maintenance. The FSC standard (for sustainable wood products) is a good example.

What do they say?

There are two big groups of standards: guidance standards and specification standards. Most people naturally assume that all standards dictate certain practices. Standards that don’t dictate something may not really feel like standards. However, many standards relevant to sustainability are guidance standards of just this kind. That means they provide recommendations, but do not specify requirements that have to be met. And there is no mechanism for proving that you have abided by the standard.

Guidance standards include types of standard like industry (or civil society or government) Codes of Practice. Others express aspirations for ideal behaviour. The Global Compact, which sets out a series of economic, social and environmental aspirations, is an example of this type.

Specification standards set requirements for how things must be. These have to be written very precisely so that it is possible to tell whether or not things have actually been done as prescribed. This makes them especially boring, technical documents — whatever their worth in relation to sustainability. ISO 14001 and OHSAS 18001 (for health and safety systems) are specification standards. Many specification standards also contain elements of guidance.

Another useful distinction between different standards is between those that concern the process of managing something and those that describe the actual sustainability performance of a company. An example of a process standard would be ISO 14001, which is concerned with how environmental performance should be managed, but does not cover what performance should be aimed at. An example of a standard that describes actual performance would be ISO 26000 (at least in some areas). ISO 26000 covers many substantive issues including human rights, consumer marketing and community development.

What are they about?

The ‘subject matter’ of a standard is the set of characteristics that the standard is trying to standardise. For sustainability standards these may be social issues (such as the labour conditions of those cutting flowers), environmental issues (like the quantity of pollution an industrial process emits) or economic issues (including the extent of corruption). There are many standards that deal with very specific issues and products only, such as the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

How do you know?

The process for discovering whether or not an activity or product conforms to a specification (‘requirements’) standard, or complies with the law, is called variously ‘monitoring’, ‘auditing’ or ‘providing assurance’.

The auditing process may result in a statement or certificate that gives the auditor’s opinion on whether or not the standard has been followed. Such standards are called ‘certifiable’. See the box below on whether this is a good idea.

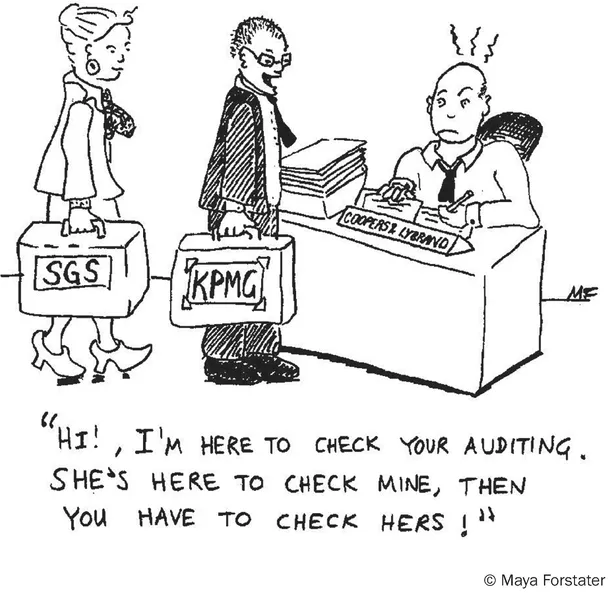

The whole idea of applying standards may appear somewhat recursive. So, there are standards for auditing, such as AA1000 AS for auditing sustainability reports. Moreover, the process for determining who is qualified to be an auditor is sometimes itself standardised, when it is generally called ‘accreditation’.

Is certifiability a good idea?

The proponents of certifiability argue that:

- The additional rigour with which requirements are specified (compared to recommendations for guidance) leads to greater attention to the issue and greater confidence in assessing progress, perhaps together with an increased chance of implementation activities to address the issue.

- Without the proof that certification provides, it is not possible for external parties to be sure that substantive performance is being improved and thereby hold organisations to account. Certification is therefore an indispensable tool with which to manage performance.

- Certification can offer a financial incentive for organisations that can demonstrate compliance by potentially differentiating themselves from their competitors.

The arguments against certifiability are that:

- The rigour necessary for specification can be misplaced, particularly for some of the social aspects of sustainable development. While the issues may be very real (e.g. sexual harassment) it can be very difficult to define appropriate and useful measures of the impact of actions intended to promote improvement. If requirements are nevertheless defined, it is likely that they may provide a misleading picture of the actual impact.

- It can lead to a culture of ‘box-ticking’, i.e. going through the motions of managing something without any real attention being paid to it.

- Certification creates significant additional costs.

SOURCE: From Henriques, A. 2012. Standards for Change: ISO 26000 and Sustainable Development (London: IIED, http://pubs.iied.org/16513IIED.html).

Having parties

Sometimes an organisation may check on its own performance in relation to a standard, as is required by ISO management systems. This is sometimes called ‘first party’ auditing. Large organisations may well have an internal department concerned with providing such ‘internal audits’. When another organisation does it, it becomes a second party audit. This can happen when a purchasing organisation checks up on the sustainability performance of one of its suppliers. When someone who is independent of both organisations, in the sense that they have no direct interest in the outcome, does the auditing, it may be called ‘third party’ auditing.

However, the independence of an auditor will never be complete. Someone will be paying, and that is usually either the organisation itself or one of their suppliers.

Labels and initiatives

Labels are miniature, logo-like certificates typically attached to products, websites or reports. The organic label on a carton of milk is an example. The legal and commercial conditions for the use of a label are usually tightly controlled. Often a key condition of the use of a label is that the product has been sourced, manufactured or produced in accordance with a standard. This book is n...