![]()

II

SEEKING SOLUTIONS

![]()

5

Resolving Conflicts in Schools: An Educational Approach to Violence Prevention

Katharin A.Kelker

Montana State University-Billings

Butler Elementary School was built on school section land in 1906. The original white clapboard building is now surrounded by more modern brick structures that house kindergarten through fifth-grade classrooms. The playground looks out on wheat fields and clover meadows where Angus cattle graze. An idyllic scene. But what goes on inside is not always so ideal. Teachers complain that students are “disrespectful and prone to using foul language.” Fistfights occur on the playground and some children feel intimidated by classmates who bully and harass them. Teachers say they no longer can count on parents supporting the school discipline system.

Is something unusual happening at Butler Elementary School? Are problems such as physical aggression, property damage, and incivility really on the rise in schools like Butler? Is school violence occurring in rural and suburban schools as well as in urban environments? According to the Clearinghouse on Urban Education (Schwartz, 1996), youth violence, which once was thought to be an urban public school problem and a consequence of poverty and family dysfunction, is actually experienced in stable suburban and rural communities and in some private schools as well. The Centers for Disease Control and the U.S. Department of Education, Department of Justice, and the National School Safety Center have examined homicides and suicides associated with schools, examining events occurring to and from school, as well as on both public or private school property, or while someone was on the way or going to an official school-sponsored event. The original study (Schwartz, 1996) yielded these data:

• Less than 1% of all homicides among school-age children (5–19 years of age) occur in or around school grounds or on the way to and from school.

• 65% of school-associated violent deaths were students; 11% were teachers or other staff members; and 23% were community members who were killed on school property.

• 83% of school homicide or suicide victims were males.

• 28% of the fatal injuries happened inside the school building; 36% occurred outdoors on school property; and 35% occurred off campus.

• The deaths included in this study occurred in 25 states across the country and happened in both primary and secondary schools and in communities of all sizes.

Beginning with the killing at school of two girls in Pearl, Mississippi, in October 1997 and 2 months later a student opening fire on a prayer group in Paducah, Kentucky, several widely publicized school slayings occurred in small rural or suburban communities, including Edinboro, Pennsylvania; Springfield, Oregon; Fayetteville, Tennessee; and Littleton, Colorado. These frightening events triggered a strong reaction among policymakers and citizens throughout the country. School safety became a buzzword and violence prevention became a priority issue for local school boards (Hyman & Snook, 1999).

Because of these highly publicized shootings, the popular perception may be that schools are plagued and sometimes controlled by disruptive, disrespectful students who are too often violent. But the reality is something quite different. Student violence, whether in rural or urban environments, is vastly overreported and exaggerated. The National Center for the Study of Corporal Punishment and Alternatives (NCSCPA) at Temple University has been collecting data on school violence since the 1970s (Hyman & Snook, 1999). Their data show that school violence has not increased during the last 30 years. In fact, in recent years it has decreased, as has the overall crime rate. For instance, the FBI’s annual statistical report on crime released in October 1999 indicates that juvenile arrests for serious crimes dropped nearly 11% between 1997 and 1998 (Lichtblau, 1999). The U.S. Department of Education (1999) reported that despite recent violent episodes in school settings, “most school crime is theft, not serious violent crime.” Referring to school shootings, for which there are no reliable statistics prior to the mid-1990s, data show that such crimes have dropped from 55 in the 1992–1993 school year to around 40 in 1997–1998 (Hyman & Snook, 1999). Of course, this number is still unacceptable; even one death is too many, but given a national school population of over 50 million students, the current death rate does not represent an epidemic.

Though school violence cannot be documented as increasing dramatically in recent years, unfortunately what has increased is the use of guns, the tendency of younger children to commit more horrific crimes, and the national media coverage of local school murders, particularly in White suburban and rural communities (Hyman & Snook, 1999),

SCHOOL VIOLENCE VARIABLES

Rates of school violence seem to vary with school enrollment, with larger schools more likely to experience violent crime. For example during the 1996–1997 school year, one third of schools having more than 1,000 students experienced at least one serious violent crime compared to just 4% to 9% of schools with fewer than 1,000 students (“Safe Schools,” 1998). So rural and suburban schools, because they tend to be smaller and not located in highcrime areas, have a better chance of creating positive learning environments.

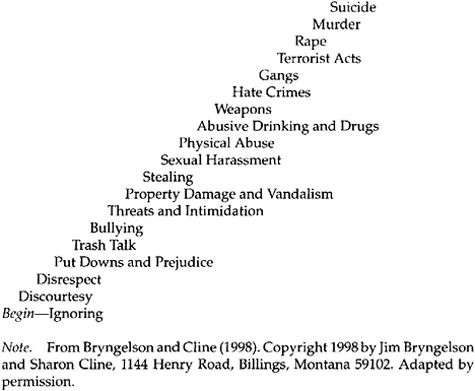

But positive school climate is apparently not an automatic condition of location in a nonurban setting. As the teachers at Butler Elementary school in the opening vignette have noted, incivility, bullying, and harassment occur in small, rural schools and may contribute to an atmosphere of tension and unrest. Bryngelson and Cline (1998) suggested that instances of violence develop along a continuum that starts with simple discourtesy but, if not addressed, can escalate to bullying, harassment, physical abuse, hate crimes, and even murder (see Fig. 5.1).

RESPONSES TO SCHOOL VIOLENCE

Though rural and suburban schools inherently may be at less risk for violence, they are not immune to conflict. Like all schools and human institutions, nonurban schools experience conflict—student versus student, student versus teacher, teacher versus teacher, teacher versus parent. The concern is not to eliminate any sign of conflict but to create a school climate in which conflicts can be resolved in healthy ways. Especially in today’s climate of concern over school violence, all schools must make safety a high priority and make a conscious effort to teach problem-solving and negotiation skills that build a framework for cooperation and the cultivation of mutual respect.

Social-Skills Instructional Models. Widespread concern about youth violence has led to the development of numerous programs intended to prevent it. The U.S. Department of Education’s (1998) document on safe schools suggests several types of prevention programs, including peer mediation, conflict resolution, problem solving, and anger management. Un-Using force to injure, hurt, threaten, or take advantage of someone or do harm to property or the physical environment.

What kinds of violence occur most frequently in your school?

What kinds of violence worry you the most in your school?

What would you add, rearrange, or delete from this continuum?

fortunately, few of these programs have been thoroughly evaluated for efficacy. Samples and Aber (1998) conducted an extensive review of the data on school-based violence prevention programs, and they concluded that many of these programs look promising but they have not been studied systematically enough to determine which methods are the most effective in reaching prevention goals. There is some evidence, however, that a comprehensive, developmental approach of education and skill building may be the most effective approach toward influencing attitudes and behavior (Lumsden, 2001).

The basic premise of social-skills instruction models is that differences of opinion and conflicts are bound to occur among adults and children in a school environment. Because conflict is inevitable, educators and students need to understand the dynamics of conflict and be prepared to manage disagreements in constructive ways. Educators can prepare themselves by developing and practicing conflict resolution skills like communication and collaborative problem solving. Students can receive training at their developmental level in social skills, problem solving, and peaceful conflict resolution. Table 5.1 presents three examples of conflict resolution activities designed to meet the developmental needs of primary, intermediate, and middle school students.

An example of a violence prevention, social-skills curriculum is the Second Step program, which is widely used with preschool through ninthgrade students. Research on the Second Step program has shown that implementation of this curriculum decreased the frequency of aggressive behaviors in third graders whereas these behaviors increased among control peer groups. The positive effects persisted for at least 6 months (M Kaufman, Walker, & Sprague, 1997).

The Second Step program provides three levels of instruction from the most general to the most specific and supportive. The first level of intervention, which is designed for all ...