1

Introduction

Definition of numerical cognition – a multidisciplinary endeavor

Checking your bank account, logging in on your smartphone, choosing the floor number in an elevator – numerical information is ubiquitous in our everyday lives. But what enables us to understand and use numerical information? Numerical cognition describes the neural and cognitive mechanisms underlying this ability. Numerical cognition covers various topics: How do we estimate the number of objects in a set? How do we understand and represent Arabic numbers and other magnitude information? How do we learn and memorize arithmetic facts and procedures? What factors determine the successful acquisition of numerical concepts during development? How can we explain specific, math-related learning disorders? These questions provide a guideline for the current book.

Like few other topics, numerical cognition benefits from contributions from a variety of complementary disciplines such as cognitive psychology, functional neuroimaging, electrophysiology, and computational modeling. I will describe the contributions of these disciplines to our understanding of numerical cognition. The description will not only cover the cognitive perspective. Rather, considering myself a cognitive neuroscientist, I will also include the neural and neuronal mechanisms that give rise to the numerical competencies we are endowed with. This also includes an evolutionary perspective when investigating numerical competencies across species – from newly hatched chicks to nonhuman primates and humans. The book will also describe the development of numerical competencies from newborn to adult age. Finally, I will demonstrate the origins and consequences of failed acquisition of numerical competencies and its remediation. I use the term numerical rather than mathematical cognition because I limit the scope of this book to basic core concepts and processes. This includes the understanding of numbers (e.g. Arabic digits), numerosities (i.e. the number of items in a set), and basic mental computations (e.g. addition, subtraction, multiplication, …). The book does not cover higher mathematical competencies such as algebra, logic, or geometry.

In the following, I will try to briefly introduce some of the central terms and the cognitive neuroscience perspective I took in writing this book. Since the introduction of these terms is not the main focus of this book, I will provide only a dramatically synthesized overview that cannot deliver the detailed knowledge provided by some of the textbooks I refer to at the end of this chapter. Providing the reader with the basic terms and concepts can nevertheless serve as an introduction to cognitive neuroscience and can help the readers’ understanding without consulting additional literature. A definition of central terms and concepts can be found in the glossary.

The term cognitive neuroscience refers to disciplines that aim at clarifying the principles of the mind at two levels. First, it includes techniques and methods that have been developed within psychology and cognitive sciences. The key motivation of these disciplines is to decipher the functional principles of the mind that give rise to (more or less intelligent) behavior. In this context, behavior does not only refer to overt behavior that is visible to the naked eye. Quite the contrary, most of the phenomena that I will describe throughout the book require the precise measurement of behavioral parameters such as reaction times in the millisecond range, finger trajectories during pointing movements or the rate at which participants are providing a correct or incorrect response over hundreds of trials. Over and above these methodological considerations, the term behavior also refers to a variety of concepts that have been conceived in order to organize mental behavior and render it accessible to scientific investigation. These include, for example, visuo-spatial attention, memory, perception, or problem solving. We will see examples for each of these throughout the book.

Second, cognitive neuroscience embraces those disciplines that investigate the principles of brain function and their relation to mental life. This comes in different flavors. Originally, clinical observations of patients with circumscribed brain damage and their associations with behavioral deficits have paved the way for a rudimentary understanding of the functional scope of a given brain area. Following brain damage (e.g. stroke), neuropsychological patients often suffer from distinguishable and sometimes unique patterns of functional deficits. The profile of these deficits crucially depends on which site of the brain was damaged, supporting the idea that different brain areas are indeed tightly associated with different cognitive functions. More information about the relationship between putatively different cognitive processes can be inferred when comparing complementary deficit patterns across patients. Finding that patient X is able to perform function a but not b while patient Y presents the exact opposite functional pattern (spared function b but impaired function a) tells us that functions a and b are independently implemented in the brain. This pattern of results is referred to as a double dissociation. For example, a double dissociation in two patients (BOO and MAR; when reporting to the public, neuropsychologists identify their patients using their initials) allowed researchers to postulate that numerical meaning can be represented in different mental codes (Dehaene & Cohen, 1997). BOO was a 60-year-old retired teacher who suffered from a left-hemispheric lesion in language-related areas. BOO was particularly impaired in solving multiplication problems (e.g. 4 × 7 = ?), while she was still able to solve addition and subtraction problems. Patient MAR was a 68-year-old, left-handed painter who suffered from a right-hemispheric lesion of posterior occipito-parietal areas. MAR was able to solve most multiplication problems but failed at very simple subtraction problems such as 6 – 2 = ? (MAR responded “2”). From this pattern of results, Dehaene and Cohen (1997) concluded that numbers can be represented in a phonological code that is important for storing arithmetic facts, and an analogue code that gives access to numerical meaning and is of pivotal importance in subtraction problems. In Chapter 2, we will learn more about the different codes and the model proposed by Dehaene and Cohen.

Neuroimaging of cognition

Recent technical developments allow us nowadays to record signatures of brain activity without intervening in mental activities or damaging the brain. Notably, the principles of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) that have been developed during the last 30 or so years allow analyzing brain processes that are associated with perception, memory or problem solving “online”, that is, while participants engage in a given activity. This is a major achievement since cognitive neuroscientists are no longer dependent on “nature’s experiments” resulting in more or less circumscribed brain lesions and their functional consequences to infer the association between different brain areas and their cognitive functions. Neither do they rely entirely on inferring cognitive processes from so-called “omnibus” measures such as reaction times. These measures are usually taken once all cognitive processes that contribute to a given function are terminated. That is, in a simple cognitive task (e.g. “What is 6 × 7?”), these measures include all subprocesses and routines such as the perception and encoding of the written input, retrieving a solution, and choosing an adequate response, for example. Neuroimaging provides an online window onto these processes while they unfold. It provides us with techniques to isolate different components of the mental activity that lead to the correct response and to study their characteristics. It is important to understand the outcome of functional neuroimaging studies. Most studies will project the statistically significant association of a given condition with changes in blood flow onto a brain template that has been created by averaging several hundred individual brain images. In the simplest of all analysis approaches, researchers contrast the brain activation from two conditions against each other (i.e. they subtract one from the other) in order to isolate those regions in the brain that are more active in one condition compared to the other. For example, researchers present participants with simple arithmetic problems (e.g. “4 × 5 = ?”) in one condition and meaningless letter strings in the other (e.g. “r k t # s”). When subtracting the latter from the former, researchers seek to isolate arithmetic problem-solving processes (i.e. activation of numerical number meaning; retrieval of the correct result from long-term memory) from more basic shared perceptual processes such as letter recognition. Comparing the activity between calculation and reading reveals areas that are more involved in mental arithmetic than letter reading, such as bilateral areas along the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), for instance. The fact that certain areas do not show up in the resulting statistical map (e.g. occipital cortex) does not imply that these areas are not involved in the task at hand. For example, we know that the occipital cortex hosts a variety of perceptual mechanisms without which we would not be able to read. It merely reflects the idea that the occipital cortex (and hence visual perception) equally contributes to both conditions (letter reading and arithmetic problem solving). Since two conditions are subtracted from each other, this is referred to as subtraction logic. In another approach, researchers parametrically vary the experimental variable of interest and seek brain areas where activation closely follows this variation. For example, when participants are asked to judge whether a given digit (e.g. 3) is smaller or larger than a given standard (e.g. 5), reaction times vary as a function of the distance between the digit and standard (here: 2). The smaller the distance, the longer the decision takes. We will see in Chapter 2 why this is the case. If we find brain areas in which the activation increases as numerical distance decreases, we can conclude that these areas are closely associated with the representation of numerical distance. This technique has a limited spatial resolution of approximately 8 mm³ to 64 mm³ and hence reflects the summed activity of millions of neurons. Other techniques in nonhuman primates allow recording the activity of single neurons at high spatial and temporal precision (e.g. 1000 Hz, meaning that 1 second delivers 1000 measurements). All of these approaches have yielded important building blocks to our understanding of how numerical cognition is implemented in the brain.

Mental representation – a key concept

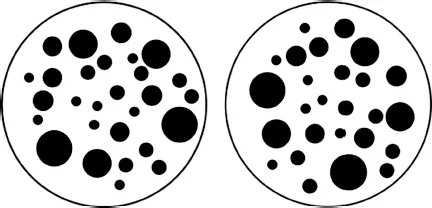

One of the most important ideas in cognitive psychology is the concept of a mental representation. A mental representation is a psychological construct. It refers to the temporary or stable mental signature that reflects previously perceived (or remembered) content or a cognitive process. Similarly, a cortical representation is the neural state that is associated with the presence of a given external or internal event. The mental representation does not necessarily need to have the same characteristics or features as the original (e.g. external) content. It is not a veridical mirror image of the original input. For example, when quickly comparing the number of elements in two sets such as the dots in Figure 1.1, you may perceive them as identical. Hence, the initial mental representation of both sets is identical. Yet when taking a second look, you may see that the left set contains two dots more than the right one. This means that our mental system (i.e. the brain) constructs representations of the external world that we operate on even if they are not veridical (i.e. exact). To understand the functional principles of the cognitive system, it is of key importance to define the content of the mental representations, their functional properties, and their deviations from the external world. For example, I will describe in Chapter 2 the human ability to determine the numerical difference between two numerosities (i.e. the number of elements in a set) and what rules this ability follows.

Figure 1.1 Two numerosities (i.e. sets of items). Guess where you see more dots – left or right?

Memory – how do we remember things?

Humans are endowed with the ability to permanently represent information in memory. Different forms of memory can be distinguished according to either the duration of retention (sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory) or to their content (procedural memory, declarative memory). Sensory memory provides a short-lived representation of sensory input (up to ~1 second), while short-term memory acts in the range of about 1 second to several minutes. Both are thought to be limited in capacity. Long-term memory, on the other hand, has a theoretically unlimited capacity and retains information for years. Declarative memory contains semantic (e.g. “6 times 4 equals 24.”) and episodic information (e.g. “I learned arithmetic facts in elementary school and I remember exactly what the classroom looked like and what smell it had.”) and requires conscious recall. Procedural knowledge is employed during the accomplishment of a task and can be retrieved without conscious control (also referred to as implicit memory). Riding a bicycle is a good example of procedural knowledge.

Much like our mental system constructs flawed representations of sensory events, the way semantic information is represented in and recalled from memory is often not a veridical snapshot of the original content. This can influence our behavior. Multiplication facts, for example, are thought to be represented in a so-called semantic network. Semantic networks consist of nodes that are interconnected with each other. Each node stands for a given piece of information. Inspired from the general network structure of neural systems, semantic networks are defined by a number of characteristics. Much like the neural system receives activating input from our senses (e.g. light falls on the retina and activates cone and rod photoreceptors), semantic networks represent information by activating certain nodes. Activation is projected along the weighted connections between nodes – much like action potentials travel between neurons. The connection between two nodes can be excitatory (i.e. activation from node 1 gradually increases activation state of node 2) or inhibitory (i.e. activation from node 1 lowers activation state of node 2). Connections vary in strength. Connection strength increases when nodes are repeatedly activated together. Another factor that determines the connection strength is the (semantical) distance between nodes. Nodes that do not share a direct connection but only an indirect one exert lower mutual influence on each other since spreading activation decreases with increasing distance.

Semantic networks can explain a number of empirical phenomena. For example, it was found that participants took more time to reject incorrect results of multiplication problems when they were part of the same multiplication table compared to unrelated responses. It takes more time to reject 28 as the response to the problem 4 × 6 = ? compared to 27. Since arithmetic facts are represented in a network structure, activation will spread to all nodes connected to 4 and 6. In this situation, the node 28, which is connected to 4, will receive more activation than the node 27 that does not share any connection (or digits) with either 4 or 6. Due to this pre-activation of the node 28, it will be more difficult for the participant to inhibit the prepotent response “correct” compared to a situation where the response alternative is not pre-activated at all.

Numerical cognition from an evolutionary perspective

Apart from the investigation of human behavior at various levels, numerical cognition has received important insights from research with non-human subjects. Surprisingly, numerical competencies have been discovered in a broad variety of species, not all of which possess a neocortex. For example, fish have been shown to swim towards the more numerous of two shoals when placed in the middle between them. Since shoals provide shelter against predators, larger shoals provide better shelter by lowering the probability of being eaten. Recognizing the larger of two shoals therefore has an evolutionary benefit. Yet a fish brain is radically different from a ...