![]()

1

UNDERSTANDING

THE POLICY PROCESS –

WHAT IS POLICY?

Key topics

• The policy cycle: problem formulation, policy formulation, objectives, implementation by instruments, impact, evaluation.

• Hierarchy of objectives.

• Intermediate and final objectives.

• Interaction between agricultural and non-agricultural policies.

• The rationales for policy intervention.

• The notion of an ‘efficient’ policy.

1.1 Introduction

It may seem odd to start a book on understanding the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the other policies of the European Union (EU) which are targeted at rural areas with a chapter which does not attempt to deal in detail with the specifics of these policies. However, as was pointed out in the Preface, this book is primarily directed at providing an explanation rather than with a description of current activities. Over time the details will alter; before the ink is dry on this page some changes will have been made to the CAP which would make a catalogue of income support mechanisms, quota arrangements, import tariffs and so on out-of-date. This enormous body of rapidly changing detailed material is well covered in the flow of official publications from the EU institutions and by information disseminated by commercial news networks and by organisations supporting farmers and other groups that are directly affected by the CAP. Much of this is now freely available in electronic form. In contrast, an understanding of the general principles and the forces at work is likely to be more enduring, providing the means to explain why policies are as they are, and an ability to assess and analyse future developments as they occur. The aim of this book is to assist the reader to reach such an understanding. The starting point must be an examination of the what we mean by ‘policy’ – any policy.

Various approaches can be used to explain and to understand the CAP. Here we mainly use economics because the toolbox this discipline provides is, in practice, immensely helpful. Economics can be described as ‘the study of how individuals and society allocate scarce resources between alternative uses in pursuit of given objectives’. As such, we can look at the objectives of policy and the way that decisions are taken to allocate resources to reach those objectives. We can recognise that some of the policy objectives are primarily political or environmental rather than to do with production or incomes, and that the outcomes of policy decisions are heavily influenced by the way in which those decisions are made. But the central thread is the scarcity of resources, which means that decisions have to be made on their allocation. This is a problem that belongs to economics.

Nevertheless, economics does provide a complete explanation the behaviour of individuals and society. Indeed, at its margins the discipline merges into political science, sociology, biology and other ways of looking at society. We will find that, in explaining the CAP and rural policy, there is a need to go some way in all these directions.

1.2 The policy process

In the present context the term ‘policy’ implies that there is some attempt by public authorities (often simplified to the ‘government’ or the ‘state’) to affect the way things are or how they turn out. Thus there may be an attempt to maintain the number of people working in the agricultural industry above the level that would otherwise occur, or to increase the area of land used for low-intensity farming beyond what would happen in the absence of government intervention. A decision not to intervene, while clearly forming a policy option, is not usually labelled as a policy, although in the UK there have been long periods in our history when such a laissez faire attitude was the norm as far as agriculture was concerned.

Policy is not just a list of state interventions (such as income support payments to farmers, grants for investment or retraining, legislation to prevent degradation of the appearance of the countryside etc.). These are merely the instruments by which policy is put into practice. Rather, policy can be seen as a process of related steps or stages in which each step leads to the next in a logical progression – a ‘rational’ model – in an attempt to tackle problems faced by society. This approach seems particularly appropriate for EU policies directed at agriculture and rural development where the aims are set out in legislation.

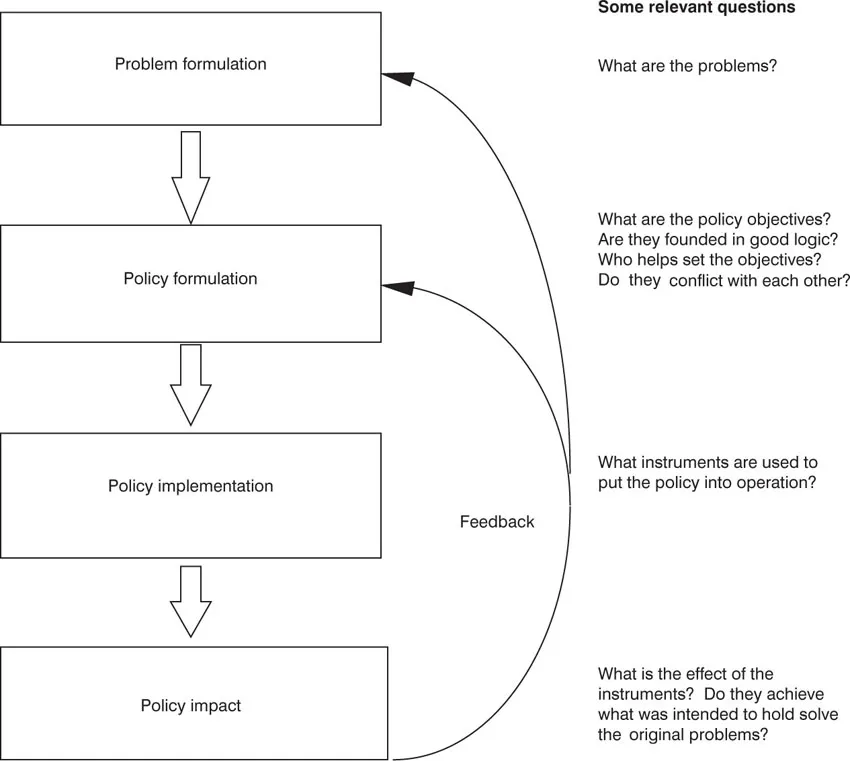

We must start with an outline of the policy process, as this forms the framework of all that follows. Later parts of this book tackle various parts of the process in greater detail. The policy process has four basic stages, shown in Figure 1.1, namely Problem formulation, Policy formulation, Policy implementation and Policy impact. Other writers have identified a greater number of stages by subdividing these four, but the basic framework of the approach is broadly agreed. These stages relate to four fundamental questions:

Figure 1.1 The policy process

1 What is the problem that makes the policy necessary?

2 What is the policy trying to achieve in order to solve (or partly solve) the problem?

3 What mechanism (instrument) is used to achieve the objective?

4 How successful is the chosen mechanism in relation to the policy problem that started the process off?

From the purpose of analysing existing policies, including the CAP, such a set of logical stages is very helpful. It is the approach traditionally taken in introductory books on public policy, and the hope is that readers will find it a convincing and useful way of looking at the CAP. However, it must be conceded that in the real world the ways in which decisions are reached can at times be far removed from the ‘rational’ model. Some analysts of public policy on defence or healthcare or immigration question whether governments have much of an idea about what they are trying to achieve, suggesting that they are primarily concerned with ‘muddling through’ and that public resources are often used irrationally. Even where the policy process model is more obviously applicable, as in agriculture and rural development, people responsible for making decisions in national government departments or EU institutions often face confused situations in which crises arrive unpredicted and demand quick fixes which are often less than perfect solutions to the problem in hand and which can carry implications that are often unforeseen. Even when time is not so short, pressure comes from bodies representing people affected by the policy to take decisions that favour their members. Information on which to base decisions, including the nature of the problem and what can be done about it, may be incomplete or biased, The institutions of government themselves often have their own motives for favouring certain decisions (such as departments wanting to extend their powers and budgets) and individual politicians and administrators may also see advancement of their careers being helped or hindered by the way that decisions go. Alternative views of the way in which the process actually works can be taken, touched on later.

Nevertheless, the view of the policy process as a set of stages linked systematically by an underlying rationale is a useful starting point for explaining policy, even helping to predict it. Though a simplification, it can usually be detected behind what goes on in the complex real world.

1.3 Problem formulation

The first stage is the recognition that there is a need for some public intervention. In some cases the need for action is blindingly obvious. For example, if people are in danger of starving because the nation’s food supply is threatened by war or its aftermath (as happened in many countries of Western Europe in the 1940s), any reasonably competent government will realise that it faces a problem and will wish to do something about it. In many other cases, though, the recognition of a problem’s existence will be less immediate. For example, the awareness in many European countries (including the UK) that farming has been encroaching on wildlife to the extent that society now wishes to protect the natural environment required the recognition that there was a danger in continuing in the old ways. Government was forced to come to terms with the fact that changes were taking place largely because individuals and then groups started to make a fuss which, eventually, politicians and senior civil servants in departments responsible for agricultural and environmental policy had to take seriously. Questions then were asked by government, such as: ‘What is the real extent of the loss of hedgerows and birds?’ and ‘Does it matter?’

The specific problems that the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy is attempting to address are considered in detail later (Chapter 2). Here it is convenient first to set out in a general way the basic sorts of problems that policy has to contend with. It will become clear that those tackled by the CAP fit into (or are ‘nested’ within) these general problems.

1.3.1 Inherent problems of a capitalist market economy – ‘market failure’ and the motives behind policy

Some problems arise because of the very nature of the type of economic system in which we live. It is worth reminding ourselves that, in the Member States of the EU, the market mechanism, with its associated prices for inputs and products, is the main way in which the fundamental decisions of what is produced, how it is produced and who gets what is produced are settled, though in agriculture there has been a history of state intervention in the system. The free interaction of supply and demand in the market has many admirable properties for this purpose.

• It operates as a way of reflecting willingness to purchase and to produce without the need for a mass of data collection and planning (as was the case in the formerly centrally planned countries of Eastern Europe). Those entrepreneurs who respond to meet consumer demands sell their output and prosper, serving the interests of both themselves and their customers. Industries where demand is growing will expand and those where demand is falling will contract.

• Competition between producers means that resources go to those who can use them in the most effective way. Efficient producers grow, while the inefficient are squeezed out and new technologies which make production more efficient get taken up.

• Comparative advantage leads to specialisation and exchange, resulting in trade both within countries and across national boundaries.

• Because the market mechanism involves equilibria, such as between supply and demand, the system is largely automatic and can for the most part be left to itself as tastes change, incomes rise which alter the pattern of demand, new technologies and new products are developed and so on.

However, a completely free market is not a perfect way of solving the basic economic problems. Flaws occur in various forms and governments will wish to intervene to modify the outcomes, ‘correcting’ for what they perceive to be problems caused by the failures of the system and aimed at achieving a better overall result in terms of the welfare of society as a whole – in other words correcting for ‘market failure’. The main deficiencies can be classed broadly as follows:

• Externalities. The market mechanism is not good at taking externalities into account. These are the outputs from production and consumption that are disregarded by the producers or consumers in their decision-making. Some are positive, such as the benefit which a farmer who installs bees in his orchard to improve the fruit yield has on the yields of neighbouring farms and gardens, whose owners benefit without bearing any cost. And a landscape shaped by ‘traditional’ farming systems may be attractive to tourists and firms looking for places in which to set up, bringing economic benefits to the local economy. However, many of these externalities are negative, such as the pollution caused by a farmer who makes silage without care to the effect of effluent on local water supplies, or the use of sprays which, in addition to controlling harmful pests on crops, kills butterflies and other insects. By failing to take into account externalities the market system does not ensure the optimum use of resources from society’s standpoint (see Chapter 8). Control of many negative externalities, especially water and air pollutions, often has to be tackled on a co-operative EU-wide basis as the causal chemicals are no respecters of national boundaries. Externalities are particularly relevant to public goods and merit goods, which form increasingly important concerns of agricultural and rural policy (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 Public and merit goods

Public goods, of which the best example is the country’s defence system, are those it is impossible to exclude people from benefiting from (they are non-excludable), and when the more there is for one person, the more there is for everyone else (they are non-rival). Markets would not provide such goods at the socially optimal level because of the incentives for individuals to opt out of paying (the ‘free-rider problem’). Consequently, defence has to be organised collectively by the state and financed from taxation. A visually attractive countryside and a diverse and rich natural environment both have aspects of non-excludability and non-rivalness and have claims to be public goods. Increasingly agricultural policy is concerned with such conservation and landscape issues.

Merit goods: somewhat controversially, externalities also form the basis of the rationale for the public finance or support of ‘merit goods’. These are good and services whose consumption is believed to confer benefits on society as a whole that are greater than those reflected in consumers’ own preferences (and thus in their willingness to pay) for them. Examples include subsidies provided to grand opera companies that allow ticket prices to be reduced, to the repair of large country houses, and to historic church buildings. It is not always easy to spot a plausible externality. For example, how does attending performances of Wagner operas subsequently enable the listeners to pass tangible benefits to other people or improve the productivity of society at large? On the other hand, evidence of the benefits to the community of providing a subsidised university education to those capable of tackling it is much firmer.

• Imperfect knowledge. The demand side of the market mechanism comes, directly or indirectly, from consumers expressing their wants through their purchasing patterns. However, consumers are not always in the best position to know what is in their personal interest, as in the cases of smoking and safety precautions. This may stem from imperfect information on the part of consumers (they are genuinely not aware of the implications of their actions) or a disregard of implications of their actions beyond the immediate future. Those of us with weight problems who nevertheless still go to restaurants to celebrate minor events with calorie-laden feasts are heavily discounting the longer-term results of our indulgence. Society may take the long view that the actions of this generation must not disregard the welfare of future generations. This is particularly pertinent in periods leading up to a war, when a government may need to safeguard the nation’s ability to feed itself and the market mechanism cannot be relied on the make the necessary preparations (ensure that there are stocks of fertiliser, that land improvements are undertaken etc.). Even in peacetime there will be some people who claim that finite resources should not be depleted, and that the consumption of oil reserves by the motorcars of today is depriving energy supplies to the earth’s inhabitants of the next century. The term ‘sustainable’ is often used to mean policies that safeguard the interests of future generations. A detailed consideration of such issues would be inappropriate here, but it is important to note that they bear heavily on policy decisions to avoid the use of growth stimulants in cattle (because of the fear of long-term consequences on human health), to protect natural resources, the natural and built environment, our cultural heritage and so on.

• Monopolies and other forms of imperfect competition. The market mechanism is also subject to the growth of market power by single or groups of buyers and sellers. In agriculture it is often felt that the individual farmer is at a disadvantage when bargaining with the small number of very large businesses that buy the bulk of many agricultural commodities (wholesale dairies, cereal merchants etc. who themselves may be subject to the influence of a few large supermarket chains). The EU has a strong policy on competition, backed up with legislation and large fines, which aims at maintaining a satisfactory degree of competition within the overall economy.

• Friction in the market mechanism. The real world is a dynamic place in which changes are constantly occurring (for example, changes in the technology of production etc.). The market will signal the adjustments needed to match new conditions (for changes in output by firms and the...