![]()

PART 1

Learning a Common Language

Energy and carbon are often confused

TALKING ABOUT LOW ENERGY BUILDINGS, the director of a major UK multidisciplinary built environment company said: “Oh yes, we’ve been involved in a number of low energy buildings. Did a big one in Islington last year… (puzzled frown)…uses a lot of energy though”.

This kind of confusion is not unusual. Energy and carbon are believed to be synonymous but they are not. And a low carbon building is most definitely not necessarily low energy.

In this case, it has probably arisen for one of two reasons. Either the building has been designed as ‘low energy’, but is not performing as expected, or it has been designed to be ‘low carbon’ and he is confused about the difference between energy and carbon.

This director is to be congratulated on one thing – the company has clearly set itself a target, and has also been measuring the actual against the intended performance.

Unfortunately, the terms energy and carbon are frequently used interchangeably, when they are two very different things. Understanding the distinction between them is very important if the right decisions are to be made about investments and creating the business case to reduce energy demand, improve energy efficiency, or install renewable technologies.

Why is the distinction not clear? After all, carbon dioxide is a gas that is emitted when fossil fuels are burned. Energy is just – energy – isn’t it?

Let’s take the electric car as an example of how loose talk misleads. Electric cars are referred to as “emission free” (e.g. Daily Mail 5/9/2013). In reality, they lead to a significant reduction in local air pollution (nitrous and sulphur dioxides), as they do not emit tailpipe pollutants unlike conventional internal combustion engines. However, if they are charged using grid electricity, which they almost invariably are, then they are not contributing a significant saving in greenhouse gas emissions. Grid electricity generation is mainly fossil-fuelled and only 35% efficient overall, using three times as much primary energy as it produces in the form of end-use electricity3. So electric cars are not responsible for carbon emissions on the street, but they are responsible for carbon emissions at the national grid level (unless they are recharged using zero carbon technologies).

In the same way, heat pumps are often referred to as providing ‘free’ energy from the ground or air. However, if you want to use a heat pump to reduce carbon emissions, it will need to generate almost three times as much useful space heating energy as the electrical energy used to drive the system (including auxiliary equipment such as pumps and immersion heaters) if they are using grid electricity. (This is the Coefficient of Performance or CoP). Many installed systems do not currently achieve this.

The Energy Saving Trust has undertaken two studies to measure the performance of a large number of air and ground source heat pumps in field trials4. The first, published in 2010, analysed the results from 83 installations. Few of the heat pumps were performing as expected, with problems identified as being with one or more of specification, design, installation, commissioning or operation. A subsequent study, published in July 2013, reported the results of a series of major and minor interventions made to optimise the performance of the same heat pumps to deliver the best possible outcome5. The average CoP for ground source heat pumps was found to be 2.82 and for an air source heat pump was found to be 2.45. Only a few of the heat pumps exceeded a CoP of 3. Because heat pumps deliver low temperature heat – more bluntly, lukewarm water – it is important that they are installed in buildings with a high quality fabric so the heat doesn’t just leak away. They also need large heat emitters – underfloor heating or enlarged radiators – to work at a high CoP.

The treatment of energy and carbon in the regulatory framework

How do we reflect this distinction between energy and carbon in our regulatory framework? In a rather confused way…

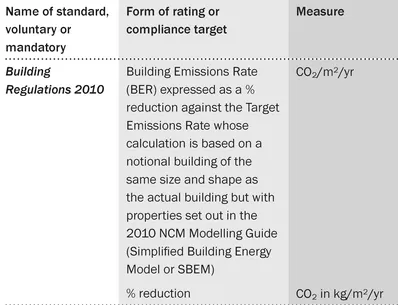

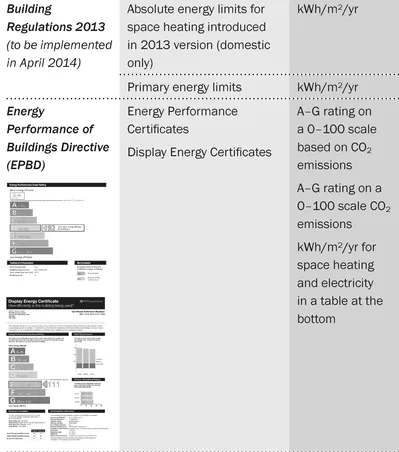

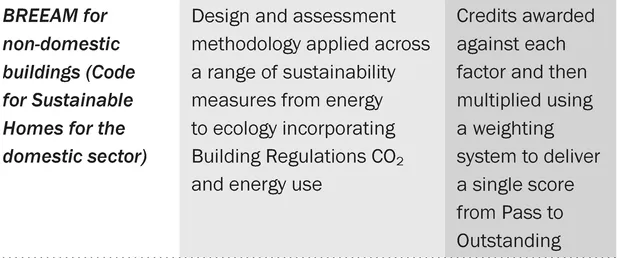

Table 1 sets out the different standards, both statutory and voluntary, which apply to new and refurbished buildings.

The table partly serves to elucidate, but also illustrates that the many different ways of talking about the energy and carbon performance of buildings are a feature of the regulatory framework. And that they use terminology that confuses rather than clarifies. So if some of the following does not seem instantly meaningful, that’s because it is unnecessarily complex. These include CO2 emissions as the headline indicator, EPC ratings with A–G and numerical scales, and display energy certificates where the main metric illustrated in the A–G grades is actually CO² rather than energy. It is not a given that a building with low carbon emissions is low energy, if higher energy demand is being met by zero carbon technologies, simply substituting higher emissions energy with lower emissions energy.

TABLE 1: Key elements of the regulatory framework

Standards expressed in carbon dioxide emissions can distract designers from delivering low energy outcomes, focusing their intention instead on usually costlier low or zero carbon technologies. Carbon emissions are intangible, invisible and not directly measurable; they need to be calculated using factors based on a range of assumptions that are also liable to change as insights develop.

More importantly, reducing carbon emissions by using low carbon technologies does not necessarily save energy (or energy costs); indeed, it may increase operating costs, whereas saving energy will generally reduce running costs. The wording of the Energy Performance Certificate also adds to the confusion where it states against the grade marker: “This is how energy efficient the building is”. Well, only if the building performs as designed… More on that later.

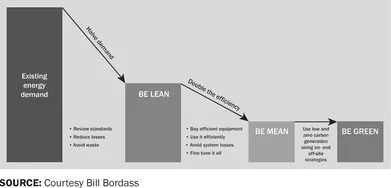

The way for us to reduce carbon emissions most effectively is to use the lean, mean, green hierarchy.

FIGURE 1: The lean mean green hierarchy

Relative versus absolute targets

The regulatory framework has generally used relative targets or percentage reductions. The starting point is the Target Emissions Rate or TER which is the CO² emissions of a notional building of the same dimensions designed to comply with 2010 building regulations. The Building Emissions rate or BER is the ‘as designed’ emissions of the real building, designed to comply with or exceed building regulations. Expressing BER as a percentage of the TER gives a figure for the relative ‘goodness’ of the design in terms of regulated energy use (those energy uses associated directly with the building rather than the discretionary activities of the occupants). So the first problem is that this percentage does not provide an instinctive sense of absolute energy performance and the second problem is that both the TER and BER are theoretical figures, often bearing little resemblance to the intrinsic energy performance of the physical building. So, in theory carbon emissions may be reduced by 44%. But this is no more than a theory.

If you don’t know where you want to go, all roads are equally good…

It is more robust and much clearer to take energy values as the primary target, which can subsequently be measured, both overall and by end-use.

How many miles per gallon does your building do? Using a simple, easy-to-understand metric like mpg that focuses attention on the final outcome would make a major contribution to improving the energy performance of our buildings. An absolute energy target defines the intended outcome in terms that are directly measurable. It provides a clear, understandable goal for energy outcomes for the client, the building manager, and its occupants.

This is not to argue for dropping carbon emissions as an indicator. Clearly reducing emissions is important. But any single indicator will not be adequate as each can create unintended consequences of one kind or other.

The Display Energy Certificate has separate thermal and electrical indicators and a combined indicator, which with UK policy has tended to be CO², and in other countries often primary and/or delivered energy. Indeed, the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive EPBD requires the use of a primary energy indicator in national building regulations and this is now being implemented in the UK (although the European Commission has instigated formal proceedings against the UK regarding failure to put the directive fully into national law). A primary energy indicator has the effect of placing a cap on grid electricity and requires an overall focus on energy efficiency.

What this all illustrates is that there is no substitute for simple metrics based on measurable outcomes.

kWh/m²/yr space heating

kWh/m²/yr electricity

kg CO²/m²/yr

So how many kWh/m²/yr does a low energy building use?

Embodied energy and carbon

There is also often confusion between operational energy and carbon and embodied energy and carbon. Operational carbon arises from the energy used to operate a building. Embodied carbon is a measure of the energy used and carbon emitted to make the products that are used to construct a building.

Striking the right balance can be difficult. For example, for each tonne of cement that is manufactured, a tonne of CO² is produced. However, concrete buildings can deliver very low energy (in-use) performance because they provide thermal mass. When it comes to mechanical and electrical plant and equipment, the embodied carbon and energy can be even higher (compounded by the fact that manufactured plant has a relatively low materials conversion factor – only about 10% of the primary material required to manufacture a piece of equipment ends up in the installed device).

If the carbon emissions related to operational energy use are high, the proportion related to embodied carbon is likely to be small. As the operational carbon emissions reduce, so the proportion related to embodied carbon increases. A study by NHBC comparing the overall emissions from a timber-frame and concrete-block house illustrated that, ultimately, the operational emissions dominate and the key focus should be on building with the minimum use of resources, whatever the materials chosen may be.

Furthermore, those readers of this book concerned with existing buildings will have little opportunity to affect the embodied carbon other than when undertaking retrofit measures.

Broadly speaking there will be a trade-off between embodied and operational carbon. A well-designed building can aim to minimise both.

Key Learning Points

- It is vital to be clear about the distinction between energy and carbon to make sound investment decisions.

- Reducing energy use will generally be the...