![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction to Classroom Assessment

“What makes a good teacher?” This question has been debated at least since formal schooling began, if not long before. It is a difficult question to answer because, as Rabinowitz and Travers (1953) pointed out almost a half-century ago, the good teacher “does not exist pure and serene, available for scientific scrutiny, but is instead a fiction of the minds of men” (p. 586). Some have argued that good teachers possess certain traits, qualities, or characteristics. These teachers are understanding, friendly, responsible, enthusiastic, imaginative, and emotionally stable (Ryans, 1960). Others have suggested that good teachers interact with their students in certain ways and use particular teaching practices. They give clear directions, ask higher order questions, give feedback to students, and circulate among students as they work at their desks, stopping to provide assistance as needed (Brophy & Good, 1986). Still others have argued that good teachers facilitate learning on the part of their students. Not only do their students learn, but they also are able to demonstrate their learning on standardized tests (Medley 1982). What each of us means when we use the phrase good teacher, then, depends primarily on what we value in or about teachers.

Since the 1970s, there has been a group of educators and researchers who have argued that the key to being a good teacher lies in the decisions that teachers make:

In addition to emphasizing the importance of decision making, Shavelson made a critically important point. Namely teachers make their decisions “after the complex cognitive processing of available information.” Thus, there is an essential link between available information and decision making. Using the terminology of educational researchers, information is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for good decision making. In other words, without information, good decisions are difficult. Yet simply having the information does not mean that good decisions are made. As Bussis, Chittenden, and Amarel (1976) noted:

As we see throughout this book, teachers have many sources of information they can use in making decisions. Some are better than others, but all are typically considered at some point in time. The critical issue facing teachers, then, is what information to use and how to use it to make the best decisions possible in the time available. Time is important because many decisions need to be made before we have all the information we would like to have.

UNDERSTANDING TEACHERS’ DECISIONS

The awareness that a decision needs to be made is often stated in the form of a should question (e.g., “What should I do in this situation?”). Here are some examples of the everyday decisions facing teachers:

1. Should I send a note to Barbara’s parents informing them that she constantly interrupts the class and inviting them to a conference to discuss the problem?

2. Should I stop this lesson to deal with the increasing noise level in the room or should I just ignore it, hoping it will go away?

3. What should I do to get LaKeisha back on task?

4. Should I tell students they will have a choice of activities tomorrow if they complete their group projects by the end of the class period?

5. What grade should I give Jorge on his essay?

6. Should I move on to the next unit or should I spend a few more days reteaching the material before moving on?

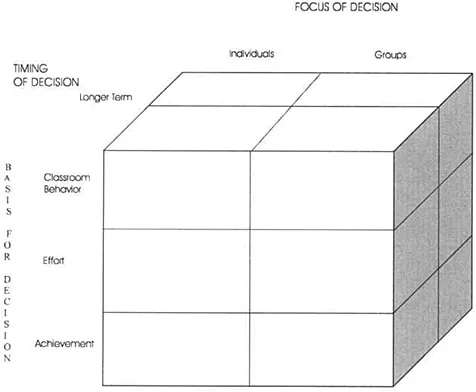

Although all of these are should questions, they differ in three important ways. First, the odd-numbered questions deal with individual students, whereas the even-numbered questions deal with the entire class. Second, the first two questions deal with classroom behavior, the second two questions with student effort, and the third two questions with student achievement. Third, some of the decisions (e.g., Questions 2, 3, and, perhaps, 6) must be made on the spot, whereas for others (e.g., Questions 1, 4, and, to a certain extent, 5) teachers have more time to make their decisions. These should questions (and their related decisions), then, can be differentiated in terms of (a) the focus of the decision (individual student or group), (b) the basis for the decision (classroom behavior, effort, or achievement), and (c) the timing of the decision (immediate or longer term). This structure of teacher decision making is shown in Fig. 1.1.

Virtually every decision that teachers make concerning their students can be placed in one of the cells of Fig. 1.1. For example, the first question concerns the classroom behavior of an individual student, which the teacher can take some time to make. This question, then, would be placed in the cell corresponding with classroom behavior (the basis for the decision) of an individual student (the focus of the decision), with a reasonable amount of time to make the decision (the timing of the decision). In contrast, the sixth question concerns the achievement of a class of students and requires the teacher to make a rather immediate decision. This question, then, would be placed in the cell corresponding with achievement (the basis for the decision) of a class of students (the focus of the decision), with some urgency attached to the making of the decision (the timing of the decision).

UNDERSTANDING HOW TEACHERS MAKE DECISIONS

On what basis do teachers make decisions? They have several possibilities. First, they can decide to do what they have always done:

• “How should I teach these students? I should teach them the way I’ve always taught them. I put a couple of problems on the overhead projector and work them for the students. Then I give them a worksheet containing similar problems and tell them to complete the worksheet and to raise their hands if they have any trouble.”

• “What grade should I assign Billy? Well, if his cumulative point total exceeds 92, he gets an ‘A.’ If not, he gets a lower grade in accordance with his cumulative point total. I tell students about my grading scale at the beginning of the year.”

Teachers who choose to stay with the status quo tend to do so because they believe what they are doing is the right thing to do, they have become comfortable doing it, or they cannot think of anything else to do. Decisions that require us to change often cause a great deal of discomfort, at least initially.

Second, teachers can make decisions based on real and practical constraints, such as time, materials and equipment, state mandates, and personal frustration:

• “How much time should I spend on this unit? Well, if I’m going to complete the course syllabus, I will need to get to Macbeth by February at the latest. That means I can’t spend more than three weeks on this unit.”

• “How should I teach my students? I would love to incorporate computer technology But I only have two computers in my classroom. What can I do with two computers and 25 students? So I think I’ll just stay with the ‘tried and true’ until we get more computers.”

• “What can I do to motivate Horatio? I could do a lot more if it weren’t for those state standards. I have to teach this stuff because the state says I have to, whether he is interested in learning it or not.”

• “Where does Hortense belong? Anywhere but in my class. I’ve tried everything I know…talked with the parents…talked with the guidance counselor. I just need to get her out of my class.”

Although maintaining the status quo and operating within existing constraints are both viable decision-making alternatives, this is a book about making decisions based on information about students. At its core, assessment means gathering information about students that can be used to aid teachers in the decision-making process.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

It seems almost trivial to point out that different decisions require different information. Nonetheless, this point is often forgotten or overlooked by far too many teachers and administrators. How do teachers get the information about students that they need to make decisions? In general, they have three alternatives. First, they can examine information that already exists, such as information included in students’ permanent files. These files typically include students’ grades, standardized test scores, health reports, and the like. Second, teachers can observe students in their natural habitats—as students sit in their classrooms, interact with other students, read on their own, complete written work at their desks or tables, and so on. Finally they can assign specific tasks to students (e.g., ask them questions, tell them to make or do something) and see how well they perform these tasks. Let us consider each of these alternatives.

Existing Information

After the first year or two of school, a great deal of information is contained in a student’s permanent file. Examples include:

• health information (e.g., immunizations, handicapping conditions, chronic diseases);

• transcripts of courses taken and grades earned in those courses;

• written comments made by teachers;

• standardized test scores;

• disciplinary referrals;

• correspondence between home and school;

• participation in extracurricular activities;

• portions of divorce decrees pertaining to child custody and visitation rights; and

• arrest records.

This information can be used to make a variety of decisions. Information that a child is a diabetic, for example, can help a teacher make the proper decision should the child begin to exhibit unusual behavior. Information about child custody enables an administrator to make...