- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is about the increasing significance of DNA profiling for crime investigation in modern society. It focuses on developments in the UK as the world-leader in the development and application of forensic DNA technology and in the construction of DNA databases as an essential element in the successful use of DNA for forensic purposes.

The book uses data collected during the course of Wellcome Trust funded research into police uses of the UK National DNA Database (NDNAD) to describe the relationship between scientific knowledge and police investigations. It is illustrated throughout by reference to some of the major UK criminal cases in which DNA evidence has been presented and contested.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Genetic Policing by Robin Williams,Paul Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introducing forensic DNA profiling and databasing

The recent incorporation of forensic DNA identification technology into the criminal justice systems of a growing number of countries has been fast and far reaching. In developing and using DNA profiling for forensic identification purposes many criminal jurisdictions across the world have followed a common trajectory: initial uses on a case-by-case basis in support of the investigation and prosecution of a small number of serious crimes (most frequently homicides and sexual assaults) have been followed by its extensive and routine deployment in support of the investigation of a wide range of crimes including property and auto crime. The recovery of biological samples from crime scenes and individual suspects, and their comparison with DNA profiles already held in police archives, has become a major feature of policing across Europe, North America and beyond. Nowhere is this more apparent than within the United Kingdom where the police forces of England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland have all incorporated DNA profiling and databasing into the routine investigation of volume crime.

The National DNA Database (NDNAD) of England and Wales is an intelligence database which holds a large collection of DNA profiles obtained from the analysis of tissue samples owned by the Chief Officers of the individual forces who provided the samples. The NDNAD was established on 10 April 1995 as the first of its kind. Until 2005 the database was managed on behalf of the Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) by the Forensic Science Service (FSS), an executive agency of the Home Office. Following the establishment of the FSS as a Government Company (GovCo) in that year, custodianship of the database was relocated within the Home Office Forensic Science and Pathology Unit. It is expected to be transferred soon to the new National Policing Improvement Agency (although the FSS still retains operational responsibility for the database). The NDNAD currently remains the largest such ‘national’ database in the world (it contains the greatest number of individual profiles and also holds the largest proportion of profiles per head of the population of any criminal jurisdiction). It includes DNA profiles which have been derived from biological samples obtained from three sources: from scenes of crime, from individuals ‘suspected of involvement in crime’ (what have usually been designated as ‘criminal justice samples’ but, since 2006, have become known as ‘subject samples’) and from volunteers (most usually obtained by the police during a mass, or ‘intelligence led’, DNA screen).

Crime scene samples are collected wherever potential biological material relevant to an investigation is identified at a crime scene by police scientific support staff or by external specialist crime scene examiners. The police are empowered to collect biological samples for the construction of subject profiles from individuals under a wide variety of circumstances and from different ‘categories’ of individuals: samples are taken without consent from those arrested for a recordable offence and with consent from volunteers. These forms of collection are supported by a legislative framework originating in 1994 and modified several times since then. All profiles which meet minimum criteria for inclusion are loaded onto the NDNAD.

Each crime scene sample DNA profile (crime scene profile) and subject sample DNA profile newly loaded onto the NDNAD are ‘speculatively searched’ against all the profiles already held on the database. Such speculative searches can potentially establish links between a crime scene and subject profiles in four different ways: a new subject profile may match a pre-existing crime scene profile (which suggests that the individual sampled may have left their biological material at a previous crime scene); a new crime scene profile may match an already recorded individual subject profile (which suggests that someone already known to have been suspected of involvement in a previous crime may also have left their biological material at a newly examined crime scene); there may be a match between a new and previously loaded crime scene profile (which suggests that the same – as yet unidentified individual – may have left their biological material at both crime scenes); or there may be a match between a new subject profile and a previously held subject profile (which suggests that the same individual has been sampled twice – either because the force which took the sample was not able to check the relevant record, or because the person sampled gave a false name). In each case, if the NDNAD produces a ‘hit’ between a new profile and a pre-existing record, the ‘DNA match’ is reported (as ‘intelligence’) to whichever police force (or forces) supplied the original samples for analysis.

In the case of samples obtained from volunteers the use of profiles for speculative searching is limited to two alternatives for which consent may be given by donors for either or both. Volunteers are invited to consent to either: the comparison of their DNA profile to profiles obtained in the course of the investigation of a specific crime (a one-off use, after which their sample and profile are destroyed); or to the loading of their profile onto the NDNAD to be retained and routinely and speculatively searched against all current and subsequently loaded profiles. This second type of consent is currently deemed ‘irrevocable’ by the enabling legislation.

In addition to each of the samples and profiles described above, the police also collect DNA from serving police officers and store the derived profiles on the Police Elimination Database (PED). Following the Police (Amendment) Regulations (2002), all new police officers are required to provide such samples as a condition of their appointment, but all officers in post before the introduction of this legislation can only be invited to volunteer their samples for inclusion. Profiles derived from these samples are held on a separate database and are used to eliminate officers’ DNA from a crime scene which may have been left there as the result of innocent contamination during investigation. The PED is not speculatively searched. It can be used only where an officer in an investigation has reason to believe that such contamination may have taken place.

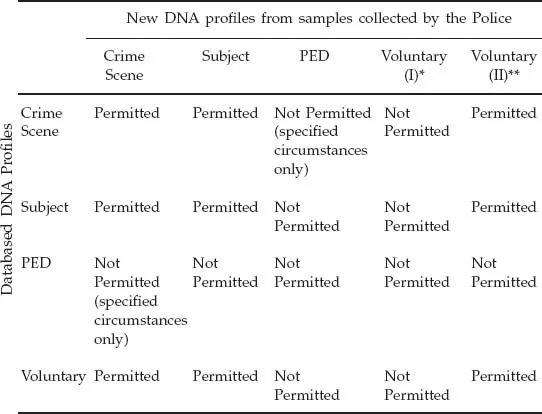

These current lawful uses of DNA profiles for speculative searching by the police are summarised in Table 1.1.

The significance of the NDNAD for criminal investigations largely lies in its provision of automated forms of speculative searching to assist in the inclusion and exclusion of potential suspects wherever relevant biological evidence yielding DNA profiles is available. Of course the use of DNA profiling for investigative and evidential purposes does not automatically necessitate the existence of a DNA archive or database: DNA samples could be collected and used simply as corroborative evidence following the identification of a suspect. Yet the existence of the NDNAD, and its capacity to facilitate speculative searches of its archive, are now central elements in the routine use of DNA for investigative purposes.

Table 1.1 Current extent of permitted speculative searching of DNA profiles

*volunteer consents for case-specific use of DNA profile

**volunteer consents for inclusion of DNA profile on NDNAD

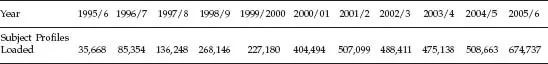

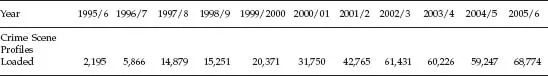

Recognition of the potential value of the NDNAD as an important source of forensic intelligence has led to the provision of substantial government investment in DNA profiling, as well as legislative support for extended powers of ‘suspect’ sampling. These two forms of support have together facilitated the very considerable expansion in the size of the NDNAD since its establishment in 1995. Tables 1.2 and 1.3, constructed from data provided in the 2005/2006 NDNAD Annual Report, show the growth in the number of subject sample profiles and crime scene sample profiles loaded onto the database since its establishment in 1995.

Each year’s newly loaded subject profiles simply add to the accumulating total of such profiles held on the database (although, in line with legislation, up to the year 2001, profiles from the unconvicted should have been removed and, up to 2003, profiles from the uncharged should have been removed). Between 1995 and 2006, 3.9 million subject profiles were added to the NDNAD, and 3.8 million of these were retained on the database as of 31 March 2006.

Table 1.2 Number of subject sample profiles loaded onto the NDNAD

Table 1.3 Number of crime scene sample profiles loaded onto the NDNAD

Between 1995 and 2006, a total of 382,746 crime scene profiles were added to the NDNAD. Unlike subject profiles, these profiles are regularly removed from the database once they have been shown to match with subject profiles. While this may be done less rigorously and less quickly than is preferred, it is done in sufficient numbers to mean that the total number of crime scene profiles on the NDNAD should include only the unmatched records of the genetic profiles of currently unidentified individuals: 121,522 of these profiles have been removed during the period in question, leaving about a quarter of a million unmatched crime scene profiles on the database as of 31 March 2006.

Approaching the NDNAD

Any effort to understand the trajectory of the technical application and operational implementation of the set of scientific innovations that constitute DNA profiling and databasing in the UK requires a dense – and sociologically sensitive – account. This account needs to attend to the interwoven series of technical, legislative and organisational changes which have underpinned this development. This is an intricate history which has been encouraged by advances in computerisation and automation which support, and are indeed engendered by, the need to incorporate the routine collection, analysis, databasing and matching of DNA profiles across the whole range of crimes investigated by the police. In this book we try to capture this complexity by outlining some of the various material, disciplinary and rhetorical resources that are brought together to make-up this socio-technical assemblage.

The most important of these resources and actions are:

• Specific bodies of disciplinary knowledge, most obviously the scientific knowledge of the form and range of genetic variation within human populations, which provide the NDNAD with its scientific base.

• The assortment of material artifacts that provide the source material for scientific analysis, including crime scene stains and tissue samples taken from criminal suspects, along with the paperwork within which the narrative of their production and subsequent preservation within a specific chain of custody is located.

• A repertoire of laboratory and computing technologies that make possible the storage and genetic analysis of bodily samples, along with methods for the representation of measured genetic variation in the form of standardised individual profiles which can be compared with one another.

• A set of very dense organisational imperatives, routines and practical actions that constitute a crime investigation process within which the material artifacts are produced, and the results of scientific analysis are deployed and audited.

• A body of regulatory frameworks which sanction the construction of artifacts and their use within the criminal justice system, including specific statutes, Home Office circulars, Chief Constables’ orders and judicial decisions.

This imbricated set of different knowledges, practices, and routines which together constitute the NDNAD has arisen and been developed within several distinct organisational contexts, but they are each given new inflections through their combination and operational redeployment in the investigation of crime. In other words, separate ‘specialist areas’ – such as genomic sequencing, forensic science practice, information technology, police investigatory procedures, and governmental expertise – are combined in the form of the NDNAD to effect its construction and deployment in certain ways and with specific aims. Therefore, of particular interest to us are the relations that have come to exist between certain sets of actors within this complex of elements. The interests and resources of these actors are not just passively combined, but rather rely upon and mutually reinforce each other in the course of the construction and continued development of the database and its deployment.

From our point of view it is neither desirable nor practical to see the development of this complex assemblage in terms of either the linear implementation of some over-arching ideological set of ambitions or as the outcome of a stochastic series of events. Rather, we would propose that the development of the NDNAD has been generated somewhere between these two poles: as a scientific potential which has been developed in accordance with specific state interests but which, because of its inculcation with such interests, has itself prospered and grown in other contexts. While we agree with Bereano (1992) that technologies are not value-free or neutral, and are themselves human interventions into social and political environments, it would be misleading to overstress the notion of a ‘governmental drive’ which simply steers the development and implementation of such innovations. But nor would we wish to expunge completely the political ambitions of the state from the development of this scientific technology; it is not simply that genetic profiling ‘affords’ certain socio-political aims (Hutchby 2001) but that those political aims have themselves contributed to the establishment of this technology (outside, as well as within, forensic science – such as in the vast market of paternity testing).

This book aims to interrogate the mutual interaction of technologies and the social networks within which they are realised. In other words, to explore how the impact of social networks has moved DNA profiling and databasing in the UK from the ‘local uncertainties’ (Star 1985) of their initial deployment within a small number of serious crime investigations to the ‘global certainties’ of their routine use for the investigation of volume crime. It is important to understand the differing contexts in which this development has been negotiated and to discern the ways in which relevant actors have invested, and contested, the implementation of DNA forensic databasing. The NDNAD constitutes a dense transfer point for a number of knowledges and practices – across science, social policy and policing – which this book aims to unpack. Of particular importance have been foundational changes in how successive governments have comprehended and approached crime and criminal justice which have, in turn, provided a rich environment for forensic science and technology to flourish. Central to this has been the development, as we explore in the next section, of a new culture of ‘crime control’. The politics of crime control or, as we prefer to term it, ‘crime management’, have been fundamental to changing conceptions of policing and to a ‘re-imagining’ of police work by government during the last two decades.

The politics of ‘crime management’

Several commentators have argued that a new culture of ‘crime control’ developed in many western societies at the end of the twentieth century (Garland 1996, 2001; Ericson and Haggerty 1997; Braithwaite 2000; Rose 2000). While there are important matters of detail that distinguish different variants of this argument, Garland characterises the general trend as this:

The most significant development in the crime control field is not the transformation of criminal justice institutions but rather the development, alongside these institutions, of a quite different way of regulating crime and criminals. (2001: 170)

Central to this contemporary regulation of ‘crime and criminals’ has been the formulation and introduction, across myriad sites and in many differing forms, of systems designed to more efficiently repress criminal conduct. This is not the development of new ways to diagnose, intervene and change the ‘moral conduct’ of an individual (although such intervention continues to be important within the criminal justice system), but rather the deployment of methods designed to intervene and delimit the corporeal activities of agents in their social life. In other words, this is the management of individual actions rather than of individuals per se. This change is characterised by Rose (1999) as a shift from a ‘disciplinary society’, in which individual behaviour is regulated by institutions (school, workplace, etc.) that mould dispositions and orientate self-surveillance, to a ‘control society’:

Control society is one of constant and never-ending modulation where the modulation occurs within the flows of transaction between the forces and capacities of the human subject and the practices in which he or she participates … Control is not centralized but dispersed; it flows through a network of open circuits that are rhizomatic and not hierarchical. In such a regime of control, as Deleuze suggests, we are not dealing with ‘individuals’ but with ‘dividuals’; not with subjects with a unique personality that is the expression of some inner fixed quality, but with elements, capacities, potentialities. (1999: 234)

Such a description serves to define a number of general understandings which now underpin the heterogeneous collection of governmental, police and private security practices designed to maximise the actuarial techniques of crime management. These strategies are designed and deployed not on ontological understandings of ‘persons’ but in relation to ‘activities’. Some have understood such a change to be one characterised by increased surveillance (e.g. Lyon 2001, 2003, 2006; Haggerty and Ericson 2006), while others have categorised it as an element of ‘risk society’ (e.g. McCartney 2006a). Certainly both risk and surveillance are central to conceptions of ‘crime management’ and to the now routine methods used to identify and control criminal conduct. In this sense, DNA databases can be seen as one of the many ways in which modern forms of government seek and use knowledge about their citizens in general, and ‘suspect citizens’ in particular (see, for example, Lyon 1991, 2001; Lyon and Zuriek 1996; Norris et al. 1996; Norris and Armstrong 1999; Marx 2002).

Here the collection and databasing of DNA profiles, as a method for providing seemingly robust and resilient knowledge about such citizens, are characterised as part of a bio-surveillance apparatus which records the past details of an individual’s criminal conduct...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introducing forensic DNA profiling and databasing

- 2 The technology of social order

- 3 From ‘genetic fingerprint’ to ‘genetic profile’

- 4 Criminalistics and forensic genetics

- 5 Populating the NDNAD – inclusion and contestation

- 6 Using DNA effectively

- 7 Governing the NDNAD

- 8 Current developments and emerging trends

- 9 Conclusion

- References

- Index